We met because of guns. More specifically, because I put a line in my Tinder profile about wanting to discuss gun regulations, and Keith wrote me back.

He had recently finished his probation period after becoming a law officer in the Seattle Police Department. But he was wary to share anything about it at first because it had lost him his last girlfriend and a handful of people he thought were friends.

“I want to tell you something,” he said on the fifth date as he grabbed my hand. A thunderstorm had just drenched us and we were taking refuge in an old pub. Scott, a guy who had spurred Keith into becoming a police officer in the first place despite not completing the process himself, had recently started acting so bizarrely that Keith had broken off the friendship. But then Scott had overheard Keith talking about women with other officers, and had called him out for disrespectful language, saying Keith, especially as a former women’s studies major, should be ashamed of himself. Keith wondered if there was any truth to the rebuke. He said he had just been joking around.

“What do you think?” Keith asked.

“About shit-talking?”

“Yeah.”

I wondered if I was supposed to be “the cool girlfriend” who didn’t mind a little crassness here and there.

“It’s hard for me to hear about,” I said. “I don’t think it’s necessary or that cool.”

He got a pained look and tried to explain team bonding while I tried to listen. I was thinking about a café owner I overheard saying that if he ever got a tattoo, it would be of his wife’s smile because he loved it so much. That’s the kind of man I hope to end up with. Someone respectful and proud of his love. Not someone who might use jokes at women’s expense as bargaining chips for masculine acceptance.

But I was also thinking about hot chocolate and our tent by a campfire. I was thinking about the flowers Keith would bring home from his garden and about the sweet, connected texts he had been sending.

Eventually Keith asked if I would hang out with some of his officer friends. We stood around eating veggie dogs with barbecue sauce, listening to shop gossip about a fellow officer who had recently said something socially offensive about a minority group. At least his friends stood up for minorities, I thought — but then they pulled up that cop’s photographs on Facebook and mocked her “unfuckable” androgyny for nearly an hour. The tone didn’t feel so awesome.

Little red flags. Or at least little red questions. But Keith got takeout burritos when I felt sick. He made me a bracelet of woven cedar strips I wore until it frayed apart. He got serious fast, accelerating from "We don’t know what this is" to "I think I’m really falling for you" in less than three months, despite knowing I was leaving at the end of summer for a science policy fellowship on the other side of the country.

Before I left, I took him on a getaway to see the places where I grew up. Out too late to find a good camping spot in the tiny beach town where we ended up, we nested down in his car. Two hours later a police officer knocked on the window and very politely asked us to leave, even pointing us to a better spot down the road. Later on that getaway, driving through sun-soaked farm country, a patrol officer caught Keith speeding, pulled him over and let him off with a warning. Both times Keith had passed the officer his police identification card along with his license.

“What’s that do?” I asked. “Does that automatically get you off?”

Keith said it was just to give the officer all the pertinent information and let him decide what to do with it. For minor driving offenses it would probably get him off. For big offenses like drunken driving Keith said it would be illegal to let anything slide.

“Good.”

By now I knew the police were Keith’s main friends and possibly his main source of identity. The police, he said, gave him a way to care about his community and give back. I could also tell they gave him acceptance and a source of purpose. Teased when he was young, he hungered especially for masculine approval. He really liked the jokes, the drinking, the solidarity, the blue-clad brotherhood of acceptance.

He was proud of it all. He showed me a video he had made of his training at the academy. Hostage situations. Shoot-don’t-shoot scenarios and evasive driving and the day everyone got gassed and asked difficult questions while tears and mucus clotted up their faces. He showed me the photo book his parents gave him and the various plaques he had been awarded and the police-themed quilt his mother had made him. I wanted to be proud of him, too. I wish I could have seen him on the job.

Though he said he wanted to leave work at home and just relax after a shift, policing permeated everything. He liked to tell me about his calls, sometimes even the tough ones, and I was glad to draw on my background as a crisis line volunteer to offer support. I asked a lot of questions and learned a lot about the day-to-day triumphs and fears. The joys of keeping Seattle safe during a jubilant Pride day celebration. The fears of split-second decisions and of being suddenly shot, like the officers in a training video he sent me.

So far, he said, he was seeing mostly professionalism from his fellow officers, and he really did think the Seattle Police Department, which the Department of Justice in 2011 had reported had “a pattern or practice of constitutional violations regarding the use of force that result from structural problems, as well as serious concerns about biased policing,” had turned a page.

We kept dating. I saw more little red flags, mostly examples of black-and-white, anecdote-based thinking. But I also saw a deeply caring man who wanted to build us a future. We went swimming, picked blackberries, had long lazy talks that made me feel we were understanding each other’s differences. I liked how he occupied the everyday trenches, trying to help others with their problems, and he liked my bigger-picture, public health emphasis on trying to make society better through systematic change and policy.

"Police" and "policy" spring, after all, from the same root: the Latin word for "civil administration."

We were lingering at sunset beside the Columbia River, when Keith brought me a few heart-shaped rocks and said he loved me. I didn’t say it back yet — the place was right but something felt shaky and premature. But a few weeks later, weeks marked by deep tenderness and awkwardly painful discussions, I said I loved him, too. Then left the state as planned. We agreed to try a long distance relationship.

On the phone a few weeks later I listened to Keith vent about Jason (the names of these officers have been changed), someone who had been through police academy with him and had possibly gotten in deep shit with a potentially vindictive administrator for using force against a suspect.

“I mean,” Keith said, “Jason would never hit anyone. I know him!”

“I feel,” I said, “like you want me to call Jason blameless and the administrator an asshole.”

Keith admitted as much. It would feel good to hear.

“But neither of us was there. We don’t know the facts.”

We hung up unsettled. I had learned that Keith did not like to be confronted. Exuberant with praise, he clammed up at a note of dissent. He compared himself to an otter: He preferred to be forcefully happy; he liked the glass half full. When the optimism cracked, I caught flashes of anger and hypersensitivity. But he had been patient, too, holding me gently when I felt stressed about leaving. There were so many things that worked for us.

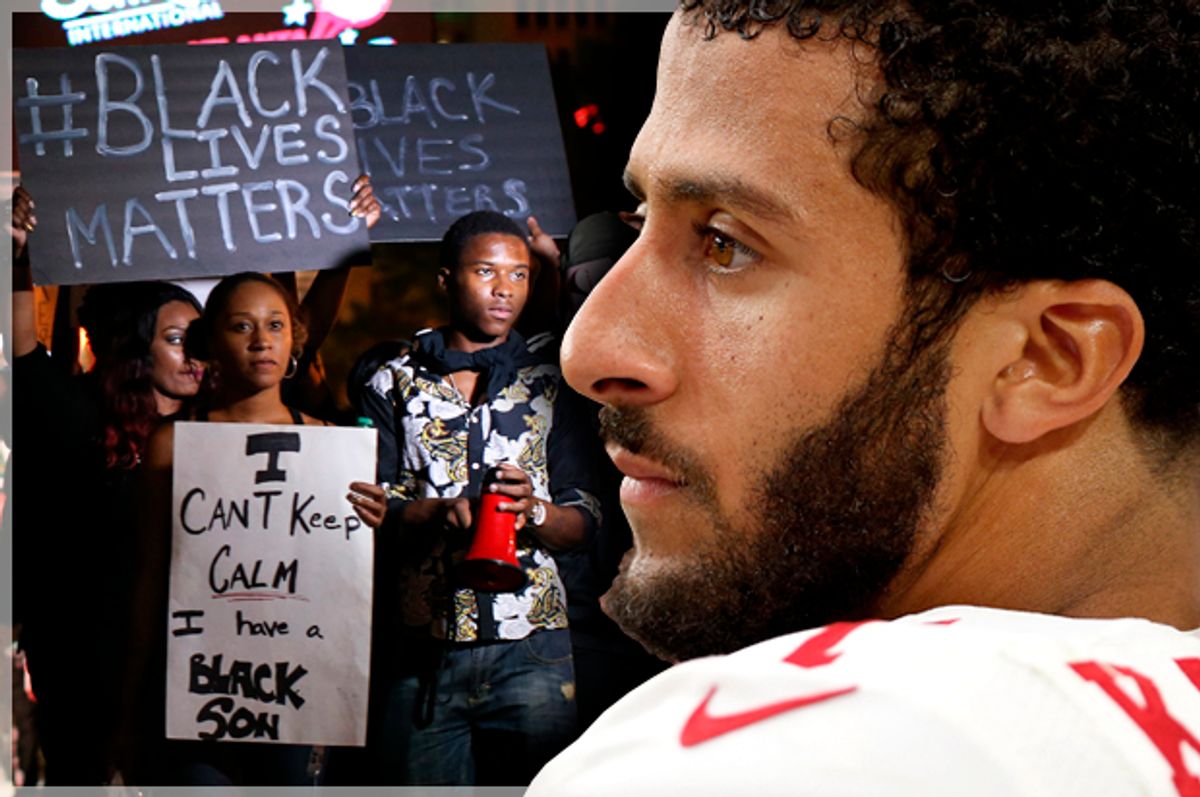

Then the National Anthem played and Colin Kaepernick took a knee and wore socks with images of pigs in police caps and suddenly a 6-foot-4-inch, 230-pound quarterback barreled between Keith and I.

“I mean,” Keith told me, “I support his right to say what he wants.” The unspoken "but"hung heavy in the air. Keith sent me an open letter by retired officer Chris Amos, who wrote that he “had the misfortune of having to shoot and kill a 19-year-old African American male.” Amos bemoaned the paucity of his pay while he was on administrative leave and went on to say: “You know Colin the more I think about it the more we seem to have in common. . . . I just had to bounce back from a gunshot wound to the chest and thigh. Good thing we both get paid when we are too banged up to 'play,' huh?”

Keith thought the letter offered a heartfelt alternate perspective to “liberal media coverage,” and I thought it was insulting. I felt like I was being forced to take a “for or against police” stance. I tried to be supportive anyway, later texting Keith about my gratitude for his being in my life.

But as the days passed, our conversations kept swinging back to blame: Why couldn’t I be more effusively supportive? Frustration, too: Why couldn’t he accept that the police are sometimes wrong (and historically often very wrong) and that people have reasons to not always trust them? Even though I was not saying anything negative specifically about Keith or the SPD, it felt like I wasn’t supposed to express any real concern about police brutality. I was supposed to just cheerfully welcome him home instead.

I brought up science, how many ways it has hurt minority populations in the past through exploitive research practices, and how some scientists are very frank about acknowledging these wounds and about doing better research going forward. Why not the police, too? Why couldn’t Keith feel my support and yet acknowledge his profession, like mine, has cause for self-criticism and sincere improvement? He didn’t respond.

I got angry. We had spent so many hours discussing policing and how much he loved it. He had been an officer less than two years, and I had been a researcher for more than six, and while he had shown what felt like real care for me, I suddenly realized we had hardly discussed my work at all. He wanted “the benefit of the doubt” and an unconditional support he did not seem interested in extending to me. I felt like he wanted researcher me to put on a police T-shirt and make the guys cookies and just shut up already. I felt he was disrespecting data, perhaps willing to disrespect women and possibly willing to disrespect me, too. While expecting me to make up for the most stressful elements of his job.

“Maybe you’re not who I thought you were,” he said.

“And maybe policing has been changing you,” I wanted to throw back at him.

He wanted so badly to be seen as a good man. I wanted so badly to be with a man who cares about me and his world both. A man strong enough to see the big picture and stand up for victims and for reform when necessary instead of buying into automatic groupthink. I just wanted to know he would always want to learn, always want to do the right thing as much as possible. I wanted a principled man. He wanted a safe woman.

“I need you to have my back,” he said.

“I need you to support my brain,” I wanted to say.

For a long time I’ve tried to understand male bonds, toxic masculinity, patriarchy, power struggles, control, heroism, and tribal culture. I see heroism in taking small daily actions to reach out to those around us. If we all create a stronger and more connected society, I think, we’ll struggle less with crime and mental illness. But I also know many people think you’re not a hero unless you put your life on the line — and that maybe once you do that you’re beyond criticism.

Keith and I had gotten into a “me versus you” attitude, a tiny echo of the “us versus them” stance the police are so often accused of. I was afraid Keith was stepping across a very clear blue line, choosing fellow officers over me and possibly, eventually, over being a true community member, too.

“I just want to come home safe,” Keith insisted. I thought of the civilians, the ones deliberately shot by police or deliberately shot by other civilians or the ones accidentally shot by someone, who don’t come home safe. I thought of the times I knew Keith had an easy shift of napping in the precinct, of working out and of waiting for routine calls. Policing is not always adrenalin and danger. Its worst chronic stress might be the weight of constantly suspecting others and just wanting to feel safer and more affirmed. I get it.

But can we always afford our own fears? I know officers are being targeted and ambushed. I also know the homicide rate for police is very similar to that for civilians. I know it feels different to walk home at dark as an unarmed young woman than it does an armed male officer. I know wives of police officers have to contend with domestic violence rates higher than the national average.

I thought back a few weeks to when friends of mine, immigrants from other countries, joined us at a little café for espresso. We talked foreign policy and how it feels for them to be new Americans. Afterward Keith said he didn’t usually like “these kinds of discussions,” but that he actually had a good time. He said political discussions usually feel adversarial. The whole time we shared coffee I was aware of how, since the café is located in his usual beat, he was off-duty conceal carrying. And how the rest of us weren’t and how the rest of us face our everyday share of problems without the backing of bullets.

On our last call, I brought up Jason, who, it turns out, did punch the suspect for attempting to bite him. “In self defense!” Keith proclaimed. Self-righteously, I mentioned how people have tried (in nursing homes, when I was a CNA) to bite me, too, and I didn’t have to punch them. Instant scoffing from Keith. Not the same thing. “But it just shows,” I protested,“that none of us knows all the facts. We can never know the whole truth about someone else. You said he would never hit anyone.”

So husky I had to ask him to repeat it, Keith abruptly muttered, “I don’t want to do this with you any more. This is a breakup.”

I said it was good while it lasted and that he was being ridiculous. Goodbye.

Keith’s first love letter to me asked if he could be my farmer, tending our relationship as one tends a garden. But it felt ultimately that I was the one committed to getting through conflict and he was the policeman trying to control how I made him feel.

The following weekend I took a trip to Baltimore. I was welcomed with the sound of sirens. Local news featured the DOJ’s condemnation of Baltimore’s policing, about the lack of police training and support, about how the homicide rate is tracking higher than ever before in the last 20 years and no one, not the police and not the community members, can find ways to stop it. An article in the Washington Post mentioned a policeman who arrested a woman for taking three of his French fries.

Ridiculous. Ridiculous that blue and un-blue lives feel locked in a war of victimization. Ridiculous that it is so difficult to gather good data on what is going on because police departments do not have to turn over their stats. How are we going to get any better if we cannot negotiate, if we cannot review data and make appropriate changes? Ridiculous, that the largest police union in the nation just endorsed Trump as their candidate. Ridiculous, that we are all so, so afraid.

Really ridiculous, that we make each other choose sides. That we try to separate the personal and the political. Keith once said he wanted it to feel like “you and me against the world.” I prefer “you and me for the world.”

Shares