A state official in Burma’s troubled Arakan state has threatened to demolish Muslim schools, homes and mosques — claiming that the structures were built illegally — in a move that could further inflame tensions between Buddhist and Muslim communities in the country.

The announcement appeared in a state government-affiliated online journal this week, according to a local news site, the Irrawaddy. Citing a state minister, Colonel Htein Lin, the report said thousands of buildings could be subject to removal, including a dozen mosques, 35 schools and more than 2,500 houses in the Muslim-majority townships of Maungdaw and Buthidaung.

But a spokesperson for Burma’s ruling party, Aung San Suu Kyi’s National League for Democracy (NLD), warned that the Arakan State government would be acting out of bounds if it tried to carry out the demolitions.

“It is against the existing rules and regulations, they don’t have the authority to demolish mosques,” NLD central-committee member Win Htein tells TIME.

Read More: Why Burma Is Trying to Stop People From Using the Name of Its Persecuted Muslim Minority

Arakan state, also known as Rakhine, was the site of deadly riots between Buddhists and Muslims that began in 2012, and tensions between the two communities have remained high in the years since. More than 100 people died in the violence, and about 140,000 others were displaced.

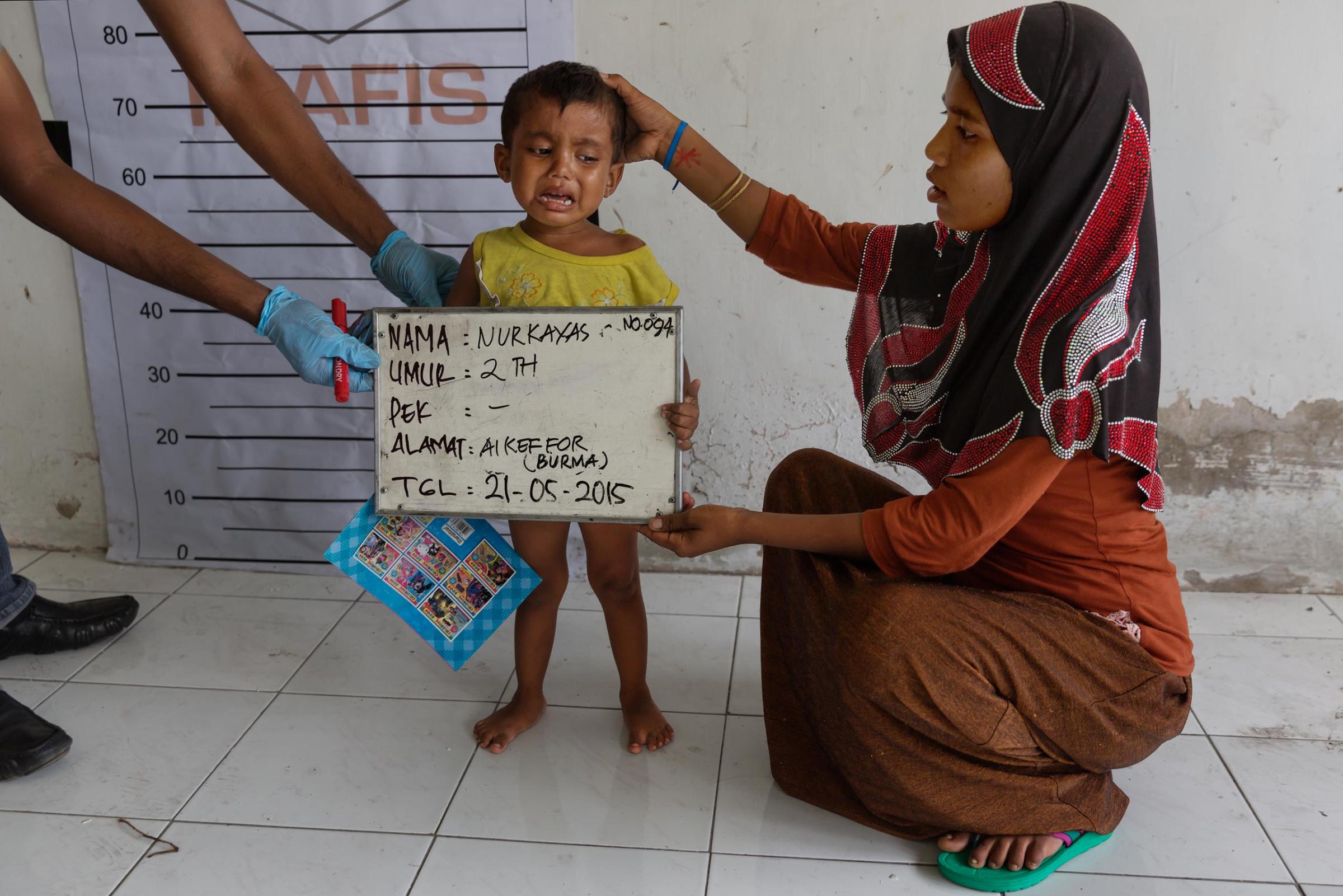

Most of those affected were Rohingya, a Muslim minority that is officially stateless and viewed by many in Burma, officially known as Myanmar, to be illegal immigrants from neighboring Bangladesh. Since the violence, about 100,000 Rohingya have been confined to squalid displacement camps where they are denied movement, education and health care.

The Plight of the Rohingya by James Nachtwey

Suu Kyi, a Nobel laureate and now Burma’s de-facto leader, addressed the U.N. General Assembly on Wednesday, pledging to find a “sustainable solution” to the crisis in the western state, though she did not refer explicitly to the Rohingya. Her new government, which took power in April, has come under international pressure to ease tensions and resolve the issue of statelessness for the persecuted group.

“We do not fear international scrutiny,” Suu Kyi said. “We are committed to a sustainable solution that will lead to peace, stability and development for all communities within the state.”

Elsewhere in the country, Buddhist-majority Burma has seen a rise in anti-Muslim sentiment in recent years, sometimes boiling over into violent outbursts. Communal riots have erupted in several major towns, and Buddhist nationalist groups have grown in size and influence. Tensions between the two communities are so sensitive that a minor dispute can trigger a major disturbance.

In June, a dispute between neighbors over a Muslim school being built in central Burma led to a mob attack that left a mosque in flames and caused dozens of Muslims to flee. Barely a week later, a mob razed a Muslim prayer hall in the country’s north. Of some 500 people reportedly involved in the attack, five were arrested.

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- The Revolution of Yulia Navalnaya

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- Stop Looking for Your Forever Home

- If You're Dating Right Now , You're Brave: Column

- The AI That Could Heal a Divided Internet

- Fallout Is a Brilliant Model for the Future of Video Game Adaptations

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Contact us at letters@time.com