There’s more to Mori Road — marking the boundary between the island city and Greater Bombay — than St Michael’s Church

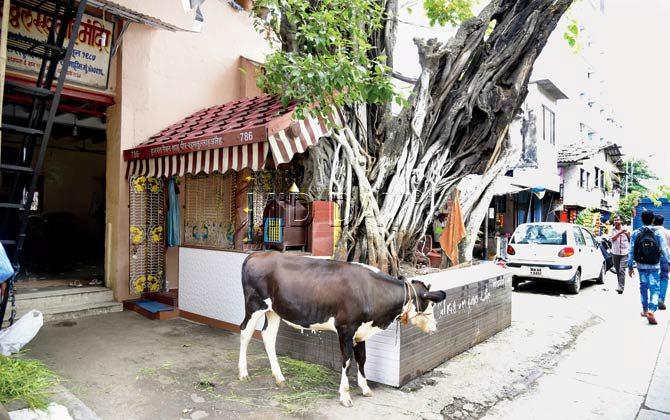

The shrines of Vitthal Mandir and Hazrat Gaitan Shah Peer Rehmatullah dargah have stood almost entwined under the same banyan for exactly a hundred years. Pics/Shadab Khan

First salaries are special. I spent mine – half of the total princely sum of 600 bucks in 1984 – treating magazine colleagues at Aram Kutchi Restaurant on Mori Road. Where’s that, astonished south Bombay voices demanded. The street of St Michael’s Church and Mahim bus depot, I explained.

ADVERTISEMENT

I was familiar with the bus stand, having boarded the same route repeatedly to visit grandparents in Dadar. Riding No. 212 from Bandra, we changed buses here to our destination. At the hint of a longer wait, my brother and I darted out to explore.

A bust of freedom fighter and social reformer Jethi T Sipahimalani at the entrance to Navjivan Society, which she founded in the post-Partition years

Mori Road (“mori” is the original Koli inhabitants’ word for shark) falls away from arterial Lady Jamshedji Road and Mahim Causeway. Yet, it has always exuded unbeatable robustness. We gawped at gypsies balanced atop wires teetering skywards and at fire eaters leaping hoops. We eyed golden batata vadas fried fresh at Prabhat Farsan, ignoring small hills of healthier water chestnuts piled in a cart by the hawker crying “Shingora, shingora”. We giggled when the dhunki instrument of the razai-pillow cotton carder twanged as a ball flew smack at him from kids at gully cricket — among them a future Indian team all-rounder.

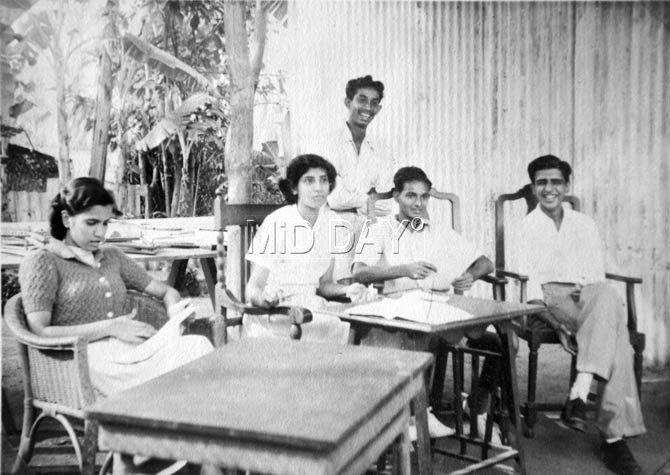

Nunu Fazelbhoy (second from left) and Shahrukh Hajeebhoy (extreme right) at a meeting of the Amateur Badminton Club (ABC), where they were introduced to each other like many Mori Road couples

Those were kitschy vignettes, no doubt. I’m grateful when family friend Murad Hajeebhoy offers a more real guided walk down the road of his childhood. His sister Zia declares Mori “the most communally diverse road in the country”. The melting pot embraces devotees kneeling at St Michael’s, the surround-sound of Azaan strains from mosques, rambunctious Koli weddings, solemn Christian funerals, Navjivan Society and Contractor Baug. Architect Mehernosh Sidikala remembers the Parsi boys’ team play cricket against the Sindhi lads of Navjivan on the then empty road connecting the two complexes.

Such cosmopolitanism hasn’t spared Mori Road going from vibrant to violent through 1992-93. The blood of coldly hatched pogroms has spilt on this street, gang wars have gripped it and bootlegging still sullies it. So, the sister shrines of Vitthal Mandir and Hazrat Gaitan Shah Peer Rehmatullah dargah make a special sight. This is the century year for both, nestled feet apart in the protective shade of an ancient banyan beside a Shiv Sena shakha.

The name Mahim derives from Mahimavati, meaning miraculous in Sanskrit. One of Bombay’s original seven islands, it was the 13th-century capital of Raja Bhimdev. Blooming under Portuguese rule, Mahim was rented for 36,057 foedeas (751-3-0 in rupaiya-anna-paisa), payable at the royal treasury in Bassein, and its custom house for 39,975 foedeas (791-2-9). With the rump of Dharavi lining it, Mori Road importantly signals the beginning of Greater Bombay (till the mid-1940s, north of Mahim was Bombay Suburban District.)

This road is interestingly bookended by the railway station on the east edge and its heritage jewel, St Michael’s Church, on the west. The city’s oldest Portuguese Franciscan church, from 1534, hosts Novena masses over nine consecutive Wednesdays for thronging thousands of believers who come worshipping from across the country. St Michael’s saw a struggle in 1853 between Bishop Anastasius Hartmann and the padroado order. Under vicars apostolic for 60 years, the church faced dissenters wanting control to rest with the padroado faction. Leading the vicars, Hartmann stated he would “rather die a martyr than surrender to schismatics”. He and his followers lay besieged within for a fortnight – their opponents blocking every entrance. On the fifteenth day, civil authorities intervened and the church reopened under the padroado group.

At the other end from this pilgrim point, the landmark level crossing with a faatak is replaced with an overpass. Where Senapati Bapat Marg nearly tails off, we pass shanties, outside which basket weavers hang their wares and rock bundled babies to sleep in ragged sari swings. Opposite, in Attarwala Chawl, looms Welcome Wafers. Inspired by Bombay chips veterans like Coronation and Janta, Velji Gada left his Kutch village of Vagal to start Welcome in the 1970s. He fried potatoes in two pans from a backroom behind his counters, “on marshy ground we were scared to tread even in daylight”. Today, they prepare 200 kilos per hour from a unit in Govandi. Before Welcome supplied crisps to clients including Famous Studios, the Taj and Oberoi hotels, they delivered packets door to door, Mahim to Byculla, because “teh cycle no jamano hato – that was the age of cycles”. I’m reminded of Sidikala’s 1960s description of sand from Gujarat brought in wooden hulls to Mahim beach, to be transported all over town.

Entering Navjivan colony we’re greeted by a statue of its onetime chairperson, Jethi T Sipahimalani, deputy chairman of the former Sind Legislative Assembly and member of the Maharashtra Legislative Council. Navjivan Society has afforded accommodation to 1,600 migrant families post-Partition in housing schemes at Mahim, Matunga, Chembur and Lamington Road.

“Jethi Sipahimalani was a lady of great refinement,” recalls retired history lecturer Lakshmi Shastri in her quietly tasteful home of 57 years. She had worried, “arriving in this jungle with no lights or concrete roads”, after marriage to Dr Jayadhratha Shastri, a widely respected physician. “But it was central and we could stroll on the pleasant seafront,” she recalls. She gently mentions bringing up a daredevil son. “Cricket balls he bowled broke windowpanes and I’d to face the music of people’s complaints!” says the mother of Ravi Shastri. When I ask him for an outstanding Mori memory, Ravi picks its levelling influence — “It was wonderful growing up with the biggest mix of communities and nationalities. From the Navjivan bottom of the road to St Michael’s we were one with Sindhis, Muslims, Parsis, Catholics, Sardars, Jews and South Indians.”

The Hajeebhoys were among the first neighbours the Shastris got to know. Meeting Murad and Zia’s parents, Nunu and Shahrukh Hajeebhoy, is a warm experience. The smiling octogenarians settle for a chat across the consulting table of Dr Rajesh Gokani, whose clinic was Dr Shastri’s. Happily, they aren’t there as patients – this happens to be a spot we converge at in the middle of our road ramble.

Like scores of Mori Road couples, Nunu Fazelbhoy paired off with Shahrukh Hajeebhoy at the Amateur Badminton Club (ABC) she formed. “She gave me love games,” her husband laughs. Scantly demurring, she declares it was the best thing for any bride to shift just a two-minute distance from the Fazelbhoy bungalow to Palmlands Society, their present residence. It is crowned with a terrace garden that is her absolute pride and joy. Nunu’s brother Sultan lives on at the Fazelbhoys’ atmospheric ancestral cottage. As he puts it: “I wake up in the room a midwife delivered me 88 years back.”

We stop next at the kholi of Bismarck Fernandes (whose son’s name is Adolf, yes), the 83-year-old whose scissors have fitted Mori Road generations. The tailor has worked in Zanzibar and Bahrain.

Though he outsources suit jackets, he continues to cut pants and shirts — “And he stitches my lovely frocks,” his sprightly young granddaughter shares. Anwar and Khalid also make a pair of veteran “masters” on this strip, at Sofistica Ladies Tailor, an enterprise Sidikala’s sister Jeroo Mehta inherited from their seamtress mother.

This is Grit Street. Character and colour, strength and tenacity thrive on its every inch. Past a rough row of kirana outlets near the post office, we reach a dusty cranny where Shibani bai sells laddoos, chana and chikki. With her painter husband’s pay, whatever meagre sums she manages to get help bring up three children.

At Maqhdoomi Restaurant we bump into Chandrakant Meher, a Koli finishing lunch where he used to savour schoolboy treats of double maska-pao and khari biscuits. “The kingfisher-filled mangroves are gone, the Mahim creek stench is foul,” he remarks. “But we have less communal clashes or bhaigiri in our area now and look forward to peace.”

Hopeful words in bleak times... With land sharks gobbling a coastline reassigned as “bay”, MHADA high-rises mushrooming and the bus depot roiled in redevelopment controversy, Mahim seems doomed on several fronts. Mori Road too might soon be left bereft of a trace of the brave little palm wadi it was born to be.

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!