- India

- International

‘India cannot survive without secularism’, says Ujjal Dosanjh

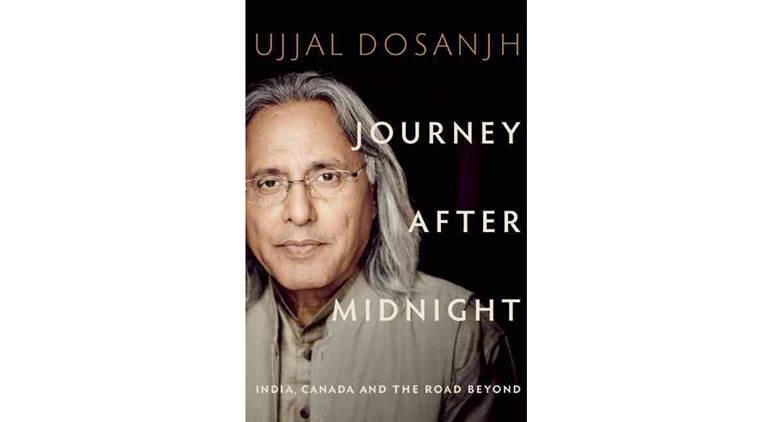

At the India launch of his memoir, Journey after Midnight, Ujjal Dosanjh talks about his life as a first-generation immigrant in Canada who was intimately involved in India’s political journey.

Former Premier of the British Columbia, Canada’s westernmost province, Dosanjh is a Canadian lawyer and politician.

Former Premier of the British Columbia, Canada’s westernmost province, Dosanjh is a Canadian lawyer and politician.

The year 1984 was one of the most violent and turbulent years in post-Independent India’s history, with not one but two incidents of mass violence coupled with sporadic incidents of violence throughout the year. One would think that the effect of this is limited to the population living in the area, but Ujjal Dosanjh proves it otherwise.

A first-generation immigrant in Canada, Dosanjh was one of the voices against the Khalistan movement that managed to give a balanced point of view of both the sides. In an interaction with journalist Seema Mustafa during the India launch of his autobiography Journey after Midnight, the self-effacing author laid bare bits of himself and his life.

Former Premier of the British Columbia, Canada’s westernmost province, Dosanjh is a Canadian lawyer and politician. He first emigrated to Britain in 1964 at the age of 18. After moving to Canada in 1968, he worked in sawmills, eventually earning a law degree.

As he stood up against the Khalistan movement in the 1980s, he faced violence, backlash and even death threats. Undeterred, however, he carried on, defending democracy and human rights. He was awarded the Pravasi Bharatiya Samman in 2003, which is the highest honour conferred by the Indian government on a non-residential Indian.

“The Khalistani movement in Canada preexisted 1984, however it happened. It was active back in the late 70s. People were making speeches and declaration of independence. But we thought they were clowns, nincompoops, nobody cared and then, June 1984 gave them legitimacy. Suddenly they were the people who were “right”” he says, adding, “Then they were more powerful. They had hit lists, (Jarnail Singh) Bhindranwale style. It was vicious propaganda against other religious groups, particularly Hindus. They were threatening Indian journalists who were fair and frank and nobody was saying anything. I had always spoken for equality and I had run twice for the legislature, so (speaking out against the movement) didn’t come out from bravery but this: that if I didn’t speak at that moment, that I kept quiet, that I would forever be silent.”

Bhindranwale, an Akali Dal leader, brought back the Anandpur Resolution into limelight, a resolution that was viewed as secessionist by the then Prime Minister Indira Gandhi. He was killed in Operation Bluestar in June 1984.

“I had written a very short letter to her after June 1984,” Dosanjh recounts. “(In her reply) she basically said that it was one of the most difficult decisions of my life, I had to make it…for the sake of the country and the Sikh. She got us into the mess we were in, in June 1984, maybe; but one thing I’m certain of…I got the sense that she was really troubled about what was happening. She said to me, ‘But the problem I have is that I don’t know who to make a deal with.’ From my perspective, I wouldn’t ascribe to the leader of the country…that she didn’t care that she killed Sikhs or that she demolished the Golden Temple or the Akal Takhqt…she made blunders but I wouldn’t go so far as to say that.”

More importantly, the impact of such movements is greatly felt on Indian emigrants, Dosanjh feels. “Religion plays an important role in the life of an Indian in Canada because there is no secular institution to serve to. In Montreal especially, there is no Indian cultural centre,” he says. The Indian diaspora, in fact, becomes more disintegrated because they tend to meet as Hindus, Sikhs, Jains, Muslims and so on instead of as Indians, he adds.

Dosanjh doesn’t maintain these incidents as historical. Instead, he finds echoes of them in the present times. “Worldwide, there is a clamour to reduce secularism. They want to actually take the modern and secular out of our lives and they think somehow, only if we could reinstate the world as it was 150-200 years ago, it was heaven – it wasn’t heaven. Ask the slaves in the US if it was heaven, Dalits in this country whether it was heaven. It wasn’t heaven,” he says.

Citing an incident from the ’60s, where a Kenyan man was afraid to sit next to him on a bus because he believed Indians were more racist than whites. It is still so. “India is the most colour conscious country, the most racist civilisation. I love India but you have to acknowledge the truth. I mean, look at the matrimonials, they want a certain colour person, certain height, certain complexion. We all do that and we think nothing of that,” he says.

Decrying the claims of kalyug, he laughs about how Indians are so proud of their satyug, with all its discrimination and inequality.

“From my perspective, India will not survive without secularism,” he states emphatically, his belief a stark commentary on the current political situation of the country. “Indians need to understand that you can’t have a country which has so many ethnic groups, so many religious groups, so many languages that it speaks, so many different faiths that it has, that you can’t survive as a diverse, just, egalitarian and compassionate society unless you have the bedrock of secularism to support all of this.”

His unabashed honesty along with his love for his home country India brings forth a gentle but firm criticism that only wishes for better conditions. Unlike other NRIs continue to long for the mitti of their land, while living abroad, Dosanjh acknowledges life outside is better and that he would probably not return. “Life is orderly, there is no corruption, life is easy…these are the things that keep you there,” he says.

Dosanjh builds on incidents from his life to show how the idealism of the early times is starkly missing in the current times, which doesn’t let people stand up against the vices. He also believes there is a lack of giant leaders – “the Nehrus, the Gandhis, the Patels are missing,” he says.

“I wish India had deference to authority. We don’t speak our minds. In the afterglow of independence, we were poor but there was excitement, exhilaration and most importantly hope. Today, there is poverty and wealth but there is absolutely no hope,” he says.

Apr 24: Latest News

- 01

- 02

- 03

- 04

- 05