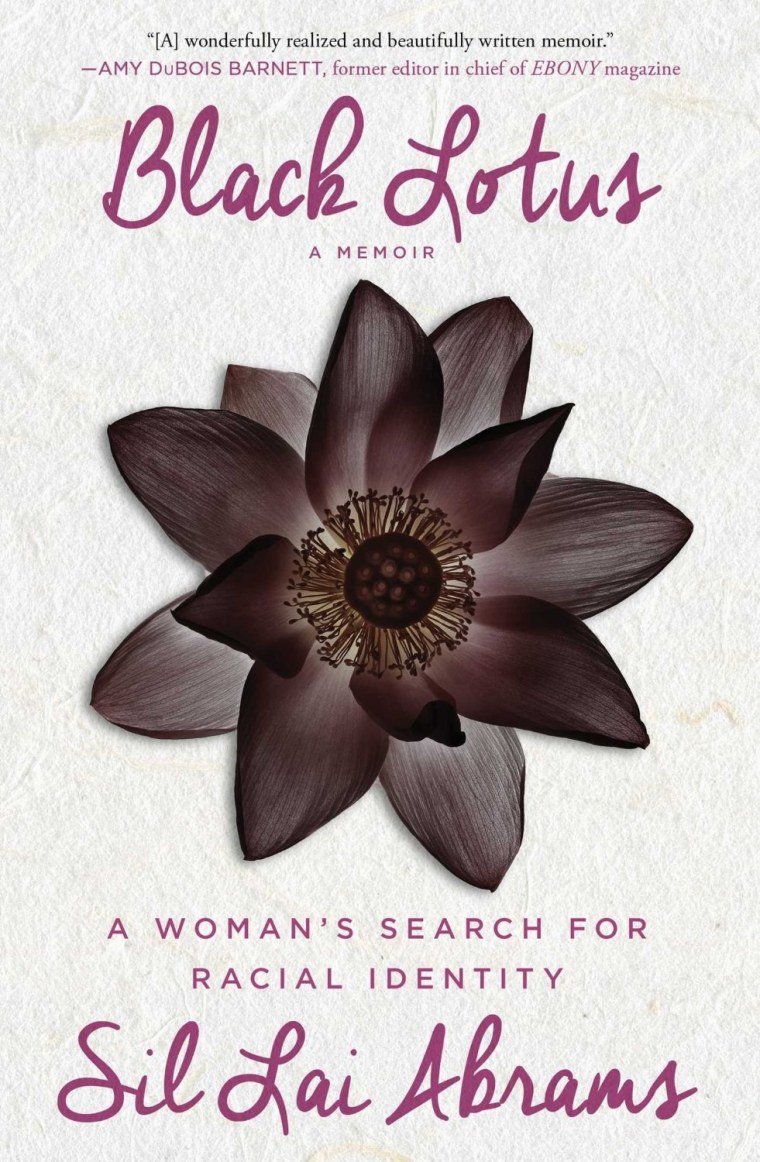

When award-winning journalist Sil-Lai Abrams finally sat down to write her memoir, she hoped to stick to her 8-month contract. Instead, it took Abrams 3.5 years to dive into the pain of her upbringing and emerge ready to tell her story in full in "Black Lotus: A Woman’s Search for Racial Identity" (Gallery Books/Karen Hunter Publishing, August 2016).

Born to a Chinese immigrant mother and a white American father in Hawaii in 1970, Abrams was raised as a white child. When school children in her Seminole County, Florida hometown would taunt her because of her brown skin and loose curly hair, with “nigger” and “porch monkey,” she took refuge in what her father had taught her: She had such tanned skin because she was born in Hawaii. It didn’t make sense to her, even as a young child, but in a world where Blackness was inferior, she clung to her father’s “Hawaiian” explanation with both hands.

She would be nearly 14 years old before her father would snatch the privilege of whiteness from her fingers. By this time, her mother had abandoned her, her father, and her two fair-skinned, straight haired younger siblings, and Abrams wrestled with self-worth as a result.

But nothing could prepare her for the despair she experienced the day her younger sister May Lai told her a racist joke about how to “stop a nigger from jumping on the bed.” Abrams’ laughed wildly at the punch line until her father entered the room, appearing upset, but not with May Lai.

“I don’t know why you’re laughing, Sil-Lai,” he said, with contempt. “You’re one.”

That’s when Abrams discovered what she’d always suspected: she was the product of an affair her mother had had with a Black man. The knowledge of her illegitimacy, particularly living within a concentrated, overtly racist community, drove her to become a blackout drunk at 15 years old, and fueled a cycle of self-destruction. Her years-long search for racial identity, self-worth and a family that would stick around culminated in New York City, where she was embraced by the Black community and developed a fierce love of her Blackness.

A recovering alcoholic for the past 22 years and mother of two adult children whom she raised to have pride in their Blackness, Abrams has survived physical and sexual assaults, abandonment, suicide attempts, depression and other mental health struggles to become a business-owner, two-time author, and advocate for abuse survivors.

In an interview with NBCBLK Abrams opens up about how her journey to find her racial identity saved her life.

You open the book with a James Baldwin quote, "You have to decide who you are, and force the world to deal with you, not with its idea of you." This book is a documentation of your lifelong journey to decide who you are for yourself. Who would you say you are today?

SIL-LAI ABRAMS: The reason why I chose that quote to open the book is, I'm still that person that has to force the world to deal with me and accept me through the lens that I have and not what is projected upon me. I see myself as a truth-teller, as an advocate and as a woman who is passionately committed to inspiring other women to share their stories unapologetically so that we can help transform this larger narrative of what it means to be a Black woman and that all of our stories are valid and there is no one correct way to do it—unless, of course, you're Rachel Dolezal, who doesn’t qualify! [Laughs]

You write about a universal need for belonging and community but so much of your life has been tainted by rejection. How do you maintain a healthy sense of self in the absence of your parents and your children’s fathers, who should’ve validated you?

I liken it to someone who has been through war: they have a devastating injury, they know it's there, it aches sometimes, but usually, they forget. I've had to be on my own for so long and have consistently faced so many rejections, even to this day. I'm an outlier, I’m very aware that I don't fit into any specific category. The way I balance it is to tell myself every day, don’t focus on those who aren't there for you. Focus on those who are. It's natural to long. Most of the time I [feel safe and whole] and then there are moments when I don't. I've come to terms with the fact that I'll probably feel like this the rest of my life.

If you're comfortable discussing this beyond what you wrote in your memoir, being sexually assaulted, the last time by a famous music producer, and your anger at the lack of justice you would receive whether you remained silent or came forward. How do you heal or deal with this failure of justice?

I don't think people speak of healing as a continuum of starts and stops. You can heal and ostensibly you feel, “Oh, that situation’s behind me.” And then something can trigger you and you are in pain again. That was always surprising about sexual assault. I don’t walk around feeling shame. I speak out against it, I share my story; it doesn't define me. But as I've become more vocal over the years about gender based violence, it's become more challenging to keep my mouth shut because I’ve got to deal with [my famous rapist] being tweeted into my [Twitter] timeline and people lifting him up as some freakin’ savior.

The poison, you get to leach it out of you through the pen, through the keyboard. It’s important if you have suffered trauma; writing is one of the most cathartic experiences.

For women in the industry, his exploits are legendary, like Bill Cosby. I'm waiting for when this man will be exposed, but I'm not going to be the sacrificial lamb. It's difficult because I'm a straight shooter, and I’d want to, but I also have to really think about rape culture, and the disparity in our income and social standing. It's still equitable to what it was when I was 24 years old when it happened and today, 22 years later. And so I have to live with it. I have to swallow my frustration and anger, and channel it into my advocacy work. That's how I keep the pot from boiling over.

I want to be able to say his name but I can’t, because if I do, I will lose everything. And I have to protect myself. It’s about choosing to survive and live and thrive. He knows the truth. The fact that we live in a culture where I've now done all the right things in theory: I'm sober, I'm not promiscuous, I don't dress provocatively, blah blah blah—all of these things that people say should protect you from sexual assault, it's BS. The moment I would say, “So and So did this to me,” all bets would be off. It's infuriating.

How do you deal?

When the news broke [about Bill Cosby being accused by over 50 women of rape and sexual assault], I didn't expect to react the way that I did. I called [a friend who’s a survivor] and I was bawling. I was hyperventilating that first week just to see the media and social media dog piling on the women [who came forward]. I said, “The only way that I'm going to find any type of peace is if I speak out.” I then made the decision to go on Al-Jazeera and talk about what I experienced and why women wait [to report sexual violence]. And it gave me peace.

RELATED: Resurfaced Nate Parker Rape Controversy Could Have Consequences

But if I didn't use my voice, it would've destroyed me. That’s why writing is so important to me. The poison, you get to leach it out of you through the pen, through the keyboard. It’s important if you have suffered trauma; writing is one of the most cathartic experiences. Survivors have to be able to speak their truth, they have to use their voice. That's why I do what I do, that's why I tell the stories that I tell.

Considering the sensitive nature of your book, how did you get into a space where you’re comfortable reliving the trauma of abuse and abandonment and loss, and then how do you get out of that space once you’re done writing it?

I have a friend who is a clinical psychologist, who asks, “are you re-traumatizing yourself by retelling [your story]?” In this particular instance, it was not traumatizing. It was very clarifying. Let's be very clear, my heart is broken still. I live with the residual trauma, so it's never far away, but I view writing as a service. Particularly a memoir that deals with such sensitive subjects, I have to try and capture various themes and incidents in as emotionally honest a way as possible which requires me to time travel and sit in that space and it was easier for me because I knew there was a purpose.

And I'm writing it as a 40-something, not as a 20-something or even a 30-something. So there is some distance from this experience. But just in general, I think that anyone that's writing this type of work needs to be sure that they're emotionally supported and in a safe enough space where they can reasonably travel back in time and not get stuck. Fortunately for me, I spent years in therapy working a lot of it out, so the sharp pain has been dulled and it's not what it was.

One thing that did give me pause throughout the book was the idea of "Black blood." Considering that Africa is the most genetically diverse continent and the history of racists who’ve used pseudoscience to justify treating people classified phenotypically as Black as inferior, how do you reconcile race as a social construct with this idea that there could be such a thing as Black blood?

The beauty is that [interpretation] depends upon the reader. You're the first person that brought up that line [in the book]. I look at it different. I see “Black blood” as strength, I see Blackness as strength. I’m not looking at it in biological terms, just your family bloodlines, what’s hereditary, which traits are passed down. And I think that there are things that I received from my father who’s Black that my siblings didn’t receive from their father. I never knew my father and I probably never will, and there will be things that will come out of his blood, and those things are good. There was something transmitted to me from my Black father and it’s why I’m still here today.

Have you continued your search for your biological father?

At the same time that I went looking for my biological mother, I embarked upon a search for my biological father. The only thing that I knew was that he was a Black Air America pilot. I contacted the Air America Association back in 1997 and spoke to whoever mans this organization and explained my situation. I can't imagine that there were that many Black pilots in Air America but they did not have a database that was broken down by race. They couldn't track someone based upon that.

RELATED: Ava DuVernay's 'Queen Sugar' is a Nuanced Portrait of Black Life

I needed a name and because my mother conveniently forgot his name, though she remembered he gave her Chanel perfume and that she had an ongoing fling with him for a year, she wasn't going to help me. So now I have thought about it, but based upon my experience with my mother and her family, I'm not prepared to embark upon what could be an equally disastrous situation. I'm not willing to do that. So I'm content. I understand who I am.

You dedicate this book to your youngest child, your daughter, Amanda. What do you hope she gets from your memoir and your life?

Being a young woman transitioning into adulthood is hard. Our girls, they need so much. I know that I wasn't there for her. There was a lot of trauma, there was a lot going on and I was there in many ways and I provided many things to both of my children, but there were ways that I failed that I touch upon in the book. I just wanted to give her something that would help her understand. Because she has her own unresolved pain around her father and what he did to me and his absence and the impact that has had on her life, having a mother who worked 80 hour weeks to provide for kids.

It's a love letter to her to embark upon her journey as a young woman, to let her know that no matter what she experiences, she can survive and thrive and that her mother loves her dearly. I hope that she will find some peace in reading the book.

The flip is she's not going to read the book right now. When she's ready, she'll read it. And someday I'll be gone and she'll have something that I never had, which is a history, to have an understanding of her mother. I had to piece this together over 46 years. I give it to her in 360 pages. Hopefully that will do some of the work for her.

I had to piece this together over 46 years. I give it to her in 360 pages. Hopefully, that will do some of the work for her.

Brooke Obie is an award-winning writer. Her debut novel, BOOK OF ADDIS: CRADLED EMBERS is available here.