Animal Instincts

When you venture into India's wildlife parks, you never know what's in store. The truth is more wonderful than anything you can ever imagine.

Picture this: it was 5.30 am, and the moon still lit the sky above Corbett National Park. We were staying at the forest resthouse at Gairal on the banks of the Ramganga river. We had spent our mornings bird-watching and the afternoons splashing in the river. Each day, we were greeted with a fresh set of pugmarks leading down to the water's edge. They belonged to a tigress who had moved here recently, cubs in tow. What didn't occur to us blithe spirits was that we could have been in real danger, frolicking in the river with a tigress nearby. Only my grandmother, Savitri, showed any signs of alarm, having lived in Kenya's wilds as a young girl. She begged us to stop,and when her warnings failed, insisted on accompanying us. "If you get eaten, I don't want to be the only surviving family member," she reasoned.

It was here that I first glimpsed a scarlet minivet, with its flaming crimson feathers. We also stumbled upon two little grey jackals, who stood transfixed for a moment before scrabbling into the undergrowth. Great or small, all creatures elicited the same excitement from us?even the ones we didn't see. We didn't see a tiger and we were lucky not to. But we did see fresh leopard scats and hoof prints of tiny boar piglets. And it was these little things that made our visit enjoyable in the extreme.

Northwest of Corbett, in the Shivalik hills, is Rajaji National Park. Its lovely forests are all that remain of a vast swathe of jungle that once sprawled across the region, allowing the elephant that lived here to thrive and roam at will. Although the forests have shrunk, Rajaji still has a vibrant elephant population. On a trip there, my family and I were staying at Satyanarayan, one of Rajaji's forest resthouses. To the delight of my posse of baby cousins, one of the park's working elephants had arrived in camp too, to spend the night. That evening, I saw a curious sight-tiny heads bobbing past my window-up and down, then back again. I decided to investigate. Stepping outside, I saw that the elephant, Lakshmi, was crunching an apple, while my littlest cousin was lovingly offering her a pear. In a short space of time, Lakshmi had been fed our entire holiday ration of fruit: kilos of oranges, pears and apples, and dozens of bananas.

That night, we piled into jeeps and set off on a night safari. "This forest is alive for those with a keen eye, a sensitive nose and a trained ear," we were told by Asha Ram,our guide. I remember thinking that I was glad to be travelling with Asha Ram's eyes, nose and ears, as we were not going to use flashlights, lest we disturb the animals. Some time later-we had been waiting at the foot of a machan for what seemed like an hour-Asha Ram motioned us to be quiet. "Shh," he said. "Can you hear the elephant?" Straining our ears, we heard a faint rustle. I pictured a herd of elephants eating their way through the foliage; but in the black of night, we couldn't see a thing and Asha Ram bundled us back into our jeeps. I can never forget what happened next. As we rounded a bend in the track, we abruptly stopped; not 10 feet away was an enormous black panther, sprawled across the road, eyes glistening in the headlights. Almost immediately, it vanished into the thicket. "See!" said Asha Ram, delighted. In all my years of wildlife watching, this was my only sighting of a panther.

My next adventure took me to Changthang wildlife sanctuary in eastern Ladakh. I was travelling with a conservation team from the Snow Leopard Conservancy India Trust. At the helm were Jigmet Dadul and Tsewang Namgail, the latter a conservation biologist who'd spent years in the region studying the critically endangered Tibetan gazelle.

Our bus was making the gruelling 12-hour journey from Leh to Hanle, set deep in the Changthang-a vast high-altitude plateau that stretches from western Tibet into eastern Ladakh. We were following the Indus, bound on both sides by lush sedge-meadows and mountains. The blue sky stretched away into the distance, where a single file of bharal (blue sheep) leapt along a mountain ridge. Tsewang asked the driver to halt. Close to the river were two of the tallest birds I'd ever seen-a pair of black-necked cranes that stood almost four-and-a-half feet tall. He was delighted to see these annual visitors, as few breeding pairs had been spotted here in recent years.

On yet another trip to the wilds, I travelled to the Kaziranga national park. We were visiting shortly after the monsoon, when the park was at its greenest, some places almost knee-deep in water. Elephant-back was the best way to see rhinos, and so we lumbered off through the tall grass one early morning. The scene before us was extraordinary-rhinos dotted the landscape, white egrets perched daintily on their backs. The annual monsoon wreaks havoc on Kaziranga and rhino calves are rescued each year. We were lucky to see a calf at feeding time at the Centre for Wildlife Rehabilitation and Conservation, outside the park. A baby rhino weighs about 50 kilos at birth and males reach an astonishing 2,000 kilos by adulthood. This baby must have guessed it had a lot of growing to do for it emptied its milk bottle at lightning speed.

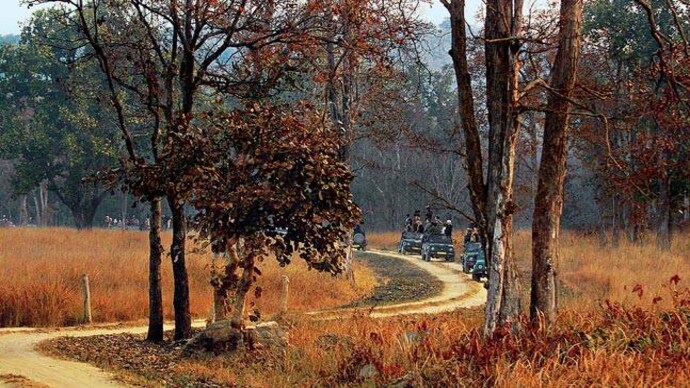

From the east, we travel to the heart of India's tiger country-the Kanha national park in Madhya Pradesh. Kanha's forests, ravines and endless meadows offer a glimpse of the once-great central Indian jungles, said to have inspired Rudyard Kipling's Jungle Book. However, its greatest achievement is its heroic revival of the barasingha or swamp deer from near extinction. I can never think of Kanha without remembering Sadan Yadav, the forest guard assigned to our jeep. He hopped in, kitted out in prescription green and rusty long-barrel shotgun. When I asked about our chances of seeing a tiger, he replied, "Every minute in the park counts- it only takes a second to see a tiger, so Positive Thinking."

Three hours and many animals later, it was closing time but still no tiger. I had all but given up hope, when three jeeps roared past us, drivers motioning "ahead ahead". "There are two cubs sitting in that grass," whispered Yadav, beginning to make short, sharp calls."Aaah-oonh-rrr," he called. After five minutes of this came an unmistakable reply. And then? Another. Two tigers! "They think it's their mother calling-come for dinner," Yadav said. "She's gone hunting and they've been alone for two days." In a breathtaking moment, the cub (if you can call an enormous 16-month-old tiger a cub), walked purposefully out of the grass. For anyone who has never seen a tiger in the wild, nothing can prepare you for the absolute awe this predator inspires. Sinews rippling gold, her sister followed. They both vanished once more into the tall grass. How a colossal cat could disappear in an instant, when common sense told you it was still there, was one of nature's great miracles. "See," said Sadan Yadav hopping with glee, "Positive Thinking."