It's back-to-school season for much of the country, but for some students, school is never out.

For some, classes are in session all year long: About 3,700 K-12 public schools across the country operate on a year-round calendar — approximately 4 percent of all U.S. schools in 2011-12, according to the latest data available from the National Center for Education Statistics.

A year-round calendar, also referred to as a balanced calendar, reorganizes the 180 school days by shortening the traditional summer break, dispersing those days into several smaller breaks throughout the year. These breaks (usually two to three weeks long) are called intersessions, and schools can use that time for remediation and enrichment programs for students. The method is popular in other countries, but U.S. research has been deemed too inconclusive to draw any long-term conclusions.

David Hornak, executive director of the National Association for Year-Round Education, an organization that advocates for shorter summers to help improve student achievement, explained to CNBC's "On the Money" that a year-round calendar helps stem summer learning loss often seen in children when they break for the extended holiday.

"On average, a teacher on the traditional calendar is required to re-teach between four and eight weeks annually after the summer intermission," said Hornak, who's also the superintendent of Holt Public Schools in Holt, Michigan — where two schools in his district operate on a year-round calendar. He referred to the findings in the 2006 published Charles Ballinger and Carolyn Kneese book "School Calendar Reform."

When learning loss compounds year after year, Hornak argued "students entering high school could be a year to a year and a half behind their counterparts on the balanced school calendar."

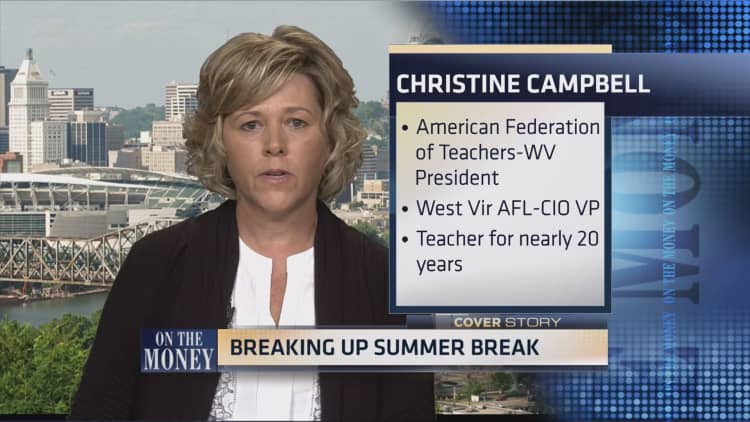

Christine Campbell, a teacher from West Virginia and the president of the American Federation of Teachers in West Virginia, said there a lot of factors are contributing to students falling behind — and it's not only due to a long summer break.

Campbell, however, said changing the calendar may not be the right solution. While there are two schools in her district that operate on a year-round schedule, she said some schools went back to a traditional calendar after being on a year-round schedule.

"Aside from the logistical problems, there are so many other things that actually improve student achievement," Campbell told CNBC.

For example, Campbell mentioned that her district has community schools. These are schools that have partnerships with community resources like health and social services. She added that by making the school a hub for the community, it strengthens the value of education.

Paying for year-round school is another big factor to consider, the educator added. "In the summer there are opportunities for federally funded programs but in the intersessions it falls down on the locals," said Campbell. "So the resources it takes to provide some of those programs we don't necessarily have in our rural areas."

Yet Hornak said he believes the resources used to address the summer learning loss could be benefiting students in a better, more efficient way.

"If we could repurpose the funds that we are putting into closing those learning gaps that we are in fact creating by operating on the traditional calendar, I just wonder what education would look like in the future," he said.

"On the Money" airs on CNBC Saturdays at 5:30 am EDT, or check listings for air times in local markets.