Shakespeare's strong-willed women

From the ruthlessness and ambition of Lady Macbeth and Margaret of Anjou to the confidence and wit of Rosalind, Viola and Portia it is often said that Shakespeare gave his best lines to women - and at a time when the roles were actually played by boys.

Dr Chris Laoutaris re-acquaints us with some of these compelling female characters and introduces a few of the powerful women who lived in Shakespeare's time and could have influenced their creation.

-

![]()

The Plays and Sonnets

Dig deeper with performances, clips and discussions from the BBC and the Shakespeare Lives partners about the sonnets and key plays including Macbeth and Hamlet

-

![]()

About Shakespeare Lives

A pioneering partnership produced by the BBC and British Council, with partners The RSC, Shakespeare's Globe, BFI, Royal Opera House and Hay Festival

Lady Elizabeth Russell (c. 1540-1609) broke all the rules. The first woman in the country to serve as the commander of a fortress, she claimed the powers of a Sheriff, instigated several riots, and owned a prison in the grounds of her country estate in Berkshire. Over the years numerous men who opposed her ended up ‘doing time’ in her personal dungeon. William Shakespeare was one of those who discovered that angering her was not a good idea.

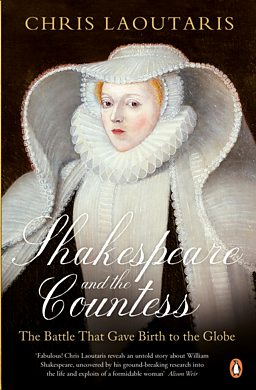

In November 1596 the theatrical troupe to which Shakespeare belonged, known variously as the Chamberlain’s Men or Hunsdon’s Men, was poised to occupy a brand-new theatre in London’s Blackfriars. Unfortunately for the players, Elizabeth Russell, self-styled Dowager Countess of Bedford, lived only paces away and got up a petition to ban them from the playhouse, a story told in my book Shakespeare and the Countess: The Battle that Gave Birth to the Globe. Lady Russell’s crusade brought the theatrical company to the brink of financial ruin. It may also have reminded Shakespeare – who perhaps needed little reminding in a country ruled by a formidable female monarch, Elizabeth I – that while women had fewer legal rights than men and were subject to an often virulently misogynistic patriarchal order, they were not always powerless.

Shakespeare would have been aware of the influential, sometimes scandalous, women who set tongues wagging.

There was the entrepreneurial Bess of Hardwick (c.1527-1608), the wealthiest female courtier in England, who married a succession of powerful men, four in all, accruing their fortunes and building the splendid Hardwick Hall in Derbyshire. Lady Penelope Rich (1563-1607) courted controversy not just because she joined her brother, Robert Devereux, Earl of Essex, in a daring rebellion against the royal court in 1601, but because she engaged in an open extra-marital affair with Charles Blount, Lord Mountjoy, maintaining a second home with him and their five illegitimate children. Lady Arbella Stuart’s (1575-1615) life combines the romance of Shakespeare’s cross-dressing comedies with the heart-breaking loss of his tragedies. Contender for the English throne, she tried to escape James I’s clutches by disguising herself as a man in a failed attempt to elope with her husband. The discovery of the plot saw her incarcerated in the Tower of London where she starved herself to death; one last act of defiance.

With numerous examples of strong-willed, feisty and independent women to inspire him, is it surprising that Shakespeare’s plays contain so many compelling female characters? Let’s re-acquaint ourselves with some of them.

-

![]()

Shakespeare’s London: playing a dangerous game

In 1598 William Shakespeare and the Chamberlain’s Men, the theatrical troupe to which he belonged, faced near-demise. Dr Chris Laoutaris investigates for the History Extra website...

-

![]()

Discover Shakespeare stories from where you live

Shakespeare on Tour: Raising the curtain on performances of The Bard’s plays countrywide from the 16th Century to the present day

Shrews, Scolds and Unruly Women

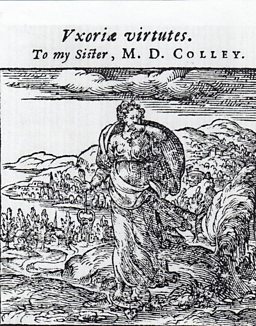

A moralising emblem from Geoffrey Whitney’s popular A Choice of Emblems of 1586 (see above) – a book Shakespeare knew well – depicts a woman standing on a tortoise, her finger pressed to her lips. An interpretative poem reveals that she “represents the virtues of a wife”, whose “finger stays her tongue” and whose willingness to “spend her days” at home is denoted by the perpetually shell-dwelling tortoise. This is a woman who lives in service of her husband, confined to her household chores while happy to “let him go where he please[s]”.

Shakespeare’s female characters often challenge this patriarchal ideal of silent and subservient womanhood...

Shakespeare’s female characters often challenge this patriarchal ideal of silent and subservient womanhood.

In Much Ado About Nothing Beatrice’s status as an orphan, free from strict paternal control, gives her a certain liberty to speak her mind and manage her destiny. The antithesis of the icon of speechless femininity, she is defined by her combative language. Benedick, with whom she engages in a “merry war”, refers to her as “my Lady Tongue” whose “every word stabs”. When her uncle Leonato expresses a desire to see her “fitted with a husband” she responds with a flat refusal to be “overmastered” by any man (2.1.56-60/246-272).

The Queen of Fairies, the “proud Titania” of A Midsummer Night’s Dream, is no less a challenger of male authority.

The Queen of Fairies, the “proud Titania” of A Midsummer Night’s Dream, is no less a challenger of male authority.

In the BBC’s recent adaptation by Russell T. Davies, Titania, played by Maxine Peake, is clad in a partially armour-plated bodice, every inch the warrior-woman as she takes on her husband Oberon. Like Beatrice and Benedick, this is a warring couple. A sub-plot of the play, removed in Davies’ edit, reveals that their argument is over “a little changeling boy” adopted by Titania. When Oberon orders her to give him the child to raise as his “henchman”, she steadfastly refuses (2.1.60-121). For the mutinous Titania the boy is a symbol of her friendship with his late mother, a female bond she honours over her obedience to her husband.

Katherina, in The Taming of the Shrew, is argumentative, disdainful of authority, given to violent outbursts and enjoys persecuting her sister. She appears to meet her match in Petruchio, a suitor from Verona. But does he really “tame” her?

Katherina fares a little better than some of the wives in the ‘taming’ ballads of the period

In many of Shakespeare’s comedies unruly women are neutralised by marriage or humiliation. Beatrice is eventually married to Benedick and does not speak again after he demands her silence with a kiss. “Peace, I will stop your mouth”, he says, reminding us perhaps of Whitney’s fantasy of tongue-tied womanhood. Titania is humiliated when she is magically induced to fall in love with Bottom, a lowly weaver who has been half-transformed into an ass. Katherina undergoes numerous humiliations, including a preposterous wedding, near-starvation, and outbursts of rage and lunacy from Petruchio. Her final speech of apparent wifely obedience, in which she describes her husband as her “head” and “sovereign” (5.2.148), has been interpreted variously as total submission, defiant sarcasm, or subtle collusion between the couple.

Katherina fares a little better than some of the wives in the ‘taming’ ballads of the period, which may have influenced Shakespeare. In the ballad A Merry Jest of a Shrewd and Curst Wife, the husband devises a novel torture for his spouse, wrapping her up in a flayed horse’s skin and promising to “make her body bleed,/And with sharp rods beat her my fill”. We may be thankful that Katherina is spared this fate. Shakespeare does, however, present us with a more nuanced play which leads us to ask if psychological torture is any less insidious than physical violence.

-

![]()

Russell T Davies and Maxine Peake at the Hay Festival

Former Doctor Who show-runner Russell T Davies talks about his passion project, the BBC film of Shakespeare’s A Midsummer Night's Dream - which he’s wanted to make his entire life. He is joined by Maxine Peake, who stars as Titania

-

![]()

Behind the scenes of A Midsummer Night's Dream

We speak exclusively to some of the big names behind the production about being involved with an epic interpretation of the Bard

Gender-bending Women

In Renaissance England women were prohibited from acting on the public stage. Female roles were undertaken by boy actors. Shakespeare adds a further layer of complexity to the drama of sexual relationships in those plays in which women disguise themselves as men.

Confident, witty and sassy, Rosalind in As You Like It counters the hackneyed protestations of love traditionally offered by men.

Confident, witty and sassy, Rosalind in As You Like It counters the hackneyed protestations of love traditionally offered by men. While incognito she responds pragmatically to her suitor Orlando’s claim that a rejection from Rosalind would cause his death: “Men have died from time to time, and worms have eaten them, but not for love” (4.1.97-8). The couple engage in role-play wooing and a mock-wedding ceremony, the sexual frisson made more piquant by the audience’s knowledge that the actor beneath these layers of disguise is male. Rosalind’s pseudonym of Ganymede – Jove’s boy lover in mythology – adds to the erotic ambiguity.

In Twelfth Night Viola is shipwrecked on Illyria. Her need for disguise – much like Rosalind’s in the forest of Arden – emphases the vulnerability of women venturing outside the home. But it also allows her to serve as adviser to the Duke of Illyria, pique the sexual interest of men and women alike, and candidly rebuke stereotypes of female desire by insisting that women are “as true of heart” as men (2.4.106).

For Rosalind and Viola the cross-dressing plot may offer a temporary freedom to travel, spar verbally with men, and escape the strictures of parental authority, but it ultimately works to get them hitched, drawing them back into their expected social roles. When we watch them in action however – or witness The Merchant of Venice’s Portia disguise herself as a male lawyer to perform a star turn in court, decimating her legal opponent – we are prompted to reflect on whether gender-roles are innate or merely parts that we all play.

Ruthless Women (or Women We Love to Hate)

The fiery preacher John Knox, in his hair-raising First Blast of the Trumpet against the Monstrous Regiment of Women, didn’t mince his words when he condemned any woman who sought to “reign above man” or take on “offices due to men” as “a monster in nature”.

Come, you spirits, That tend on mortal thoughts, unsex me here...Lady Macbeth

Shakespeare echoed contemporary anxieties associated with female ambition in many plays.

Perhaps the most well-known is Macbeth in which a steely Lady Macbeth asks the “spirits/That tend on mortal thoughts” to “unsex” her and fill her with “direst cruelty” (1.5.39-42) so that she may spur on her husband to seize the crown by murdering King Duncan. Her descent into madness, as the couple wade deeper in the blood of Macbeth’s victims, acquired an iconic status from 1779 when Sarah Siddons portrayed the sleep-walking Queen haunted by the consequences of her power-lust.

Lady Macbeth, played by Vicky McClure (Line of Duty, This is England), summons up her demons in this soliloquy from Act 1 Scene V in Macbeth.

The flesh she herself hath bredTitus Andronicus (5.3.61)

Tamora, Queen of the Goths from Titus Andronicus, displays none of Lady Macbeth’s remorse. Seducing the Emperor of Rome, she goes from being the Romans’ prisoner to becoming their Empress, and endorses the rape and mutilation of the innocent Lavinia. In revenge Lavinia’s father, Titus Andronicus, murders Tamora’s sons and feeds them to her in a gruesome banquet during which she eats “the flesh she herself hath bred” (5.3.61). Nowhere does Shakespeare more arrestingly dramatise the self-consuming nature of merciless ambition.

One of the grandest female roles Shakespeare conceived was that of Margaret of Anjou, a character spanning four plays: the three parts of Henry VI and Richard III.

In BBC2’s The Hollow Crown, which reinterprets these plays, Sophie Okonedo captures perfectly Margaret’s growing ambition for her family’s dynasty, and the increasingly elaborate scheming which leads to her being dubbed the “she-wolf of France”. But Shakespeare shows that while she becomes a vindictive player in the political games of a corrupt English court, she is also a victim of the men who vie for power in a war-torn country.

By Richard III her only defence lies in her prophesies and spine-chilling curses, which map her enemies’ self-destructive paths. This may lead to her being called a “witch” and a “lunatic” (1.3.164/254), but it also places her among the women in the play who comment on the horrors of living in a man’s world.

Sarah Siddons, the first lady of Shakespeare

Tanya Kirk, Curator at the British Library, explores the life and legacy of Sarah Siddons, one of the first women to legitimise the role of women as performers and also to take on male roles including Hamlet.

By Dr Chris Laoutaris

The Hollow Crown: Henry VI Part 2 - Sophie Okonedo as Margaret of Anjou

In a gruesome scene, Vengeful Margaret smears blood onto Plantagenet (Adrian Dunbar)

More on Shakespeare...

-

![]()

Shakespeare Lives

Experience an incredible commemoration of the Bard's 400th death anniversary with videos feauring David Tennant, Ian McKellan, Adrian Lester and more

-

![]()

Hay Festival

A great collection of actors, authors, writers, including Russell T Davies, Germaine Greer and Salman Rushdie, celebrating the Bard at the arts and literature gathering

-

![]()

Great Speeches

Watch some of the most memorable Shakespeare speeches, as chosen by the RSC, featuring Peggy Ashcroft, Patrick Stewart, Vanessa Redgrave and more

-

![]()

Quirky stories

From the Bard's influence on pop music to his face appearing on a £20 banknote, discover more unorthodox and unusual tales of Shakespeare from past to present