It was coming up on midnight when the fog began rolling in off the Atlantic, and a little after 1 a.m. when the pace car, a plastic-clad Pontiac Grand Prix, was sent out to wrangle the field after a car stalled on the track. Forty minutes later, with visibility down to less than 100 yards, the decision was made to red-flag the race: The 1989 running of the 24 Hours of Daytona would be something less than 24 hours.

Parked in the lead was the pole-sitting Nissan GTP of Geoff Brabham, Chip Robinson and Arie Luyendyk, seemingly unruffled by IMSA rule changes implemented in an effort to slow a team that had rattled off eight straight wins a season earlier; two laps back, the Castrol Jaguar XJR-9 driven by Price Cobb, John Nielsen, Andy Wallace and Jan Lammers, one of the Tom Walkinshaw cars which a year before had put an end to 11 years of Porsche dominance here and seemed to herald the walk-off music signaling that, in particular, the Porsche 962’s long moment in the spotlight was over. Not far behind the slinky, fender-skirted Jag, though, and perhaps not quite ready to leave the stage, a half-decade old and based on a design twice that, twice wrecked and rebuilt, battle-hardened and borderline obsolete, sat a Millennium Falcon of a 962 piloted by two seasoned vets and a guy with a famous name who’d spent the previous weekend driving midgets around a 1/16-mile indoor dirt track, backed by a team that had been coming to Daytona for 15 years without a victory.

The clock continued to run as Florida slept—berries ripening in the fields, orange blossoms pregnant with the perfume of early spring, dew forming on the windshields and spoilers of forty-two race cars with nowhere to go, waiting out the damp, foreboding gloom of a February morning.

With less than a year from approval to its planned

Growing up in Pasadena, Jim Busby enjoyed the type of adolescence typical of Southern California in the 1950s and ’60s: street-racing at 14, building Top Fuel dragsters by 19, towing cars to the Pomona Fairgrounds with a van full of surfboards still wet from a morning spent battling hodads. With some friends, he set off on the NHRA circuit, where, with straight faces, they called themselves the Beach Boys Racing Team. A Smothers Brothers sponsorship followed, along with national exposure and even some success, but Busby had his eye on a different target.

Inspired by a road-racing uncle—Harry Steele campaigned a Cad-Allard in the ’50s—and encouraged by Dick Smothers, he bought a Merlyn Mark 11B and promptly discovered that, as he puts it now, “the drag-racing guys were miles ahead of the road-racing guys,” and that by applying his shop wisdom to Formula Ford, he could run rings around the competition. “I read the rule book, took the engine apart, bored it .030 over and cc’d the heads and did everything we did with drag motors. … I figured out it would rev higher if I changed the valve springs every weekend instead of every year.”

An accident in a Formula 5000 car a year later brought Busby back to the quarter mile, however. While convalescing, he came up with an idea for the pile of outlawed USAC four-cam Indy Ford motors he’d picked up for a song. “I rebuilt two of them, put the pistons in my little lathe and cut the tops off of them so we could run nitro, a lot of nitromethane—Indy guys ran about 35% for qualifying, we ran about 80%—and we timed it as a 16 instead of two 8s using an Ed Donovan coupler.” The resulting twin-engined monster made just one appearance, at the 1971 Winternationals, but that was enough to draw the attention of Leonard Fass of King-O-Lawn lawnmower fame, who, when the inevitable uproar killed off USAC’s new stockblock regulations, sent a truck to Busby’s shop along with $35,000 to collect his stash of heretofore worthless engines. This time Busby had cashed in his chips for good.

By the mid-’70s, Busby was conquering IMSA GT the same way he’d succeeded in Formula Ford. Fielding a Porsche 911 RSR with an Andial motor, he tapped Valley Head Service in Northridge to make slant port injectors for the Porsche’s 3.0-liter six. “I read the rules to indicate that the manifold was free, and cylinder-head porting was free. So, we ported the cylinder heads out into an angle where it wiped out the entire side of the head … changed the intake angle on the trumpets and the injector bodies about 10 or 12 degrees, got a straight flow of air into the intake valve and passed muster with IMSA. We added 35 hp and started winning a lot of races.”

Following that inaugural win at the 1982 Le Mans race, Porsche 956s (shown, below) won, well, everything. The extent to which every scheduled event became an ever-larger swarm of 956s obliterating whatever remaining competition even bothered to show up is difficult to comprehend at this remove. A plague of locusts is less overwhelming. The Borg show their vanquished more mercy. The Porsche 956 descended upon the international racing world like an omnipotent, intergalactic entity forcing drivers of lesser vehicles everywhere into postures of helpless submission. Everywhere but in the U.S., that is, where, oblivious to the hydra-headed beast that had enveloped the rest of the planet, old-fashioned mom-and-pop race shops cheerfully continued to turn out GTP racers in the most wondrous assortment of shapes and sizes, blissfully unaware that only the thinnest of membranes—a requirement in the IMSA rulebook mandating that drivers’ feet must sit aft of the front-axle centerline—was all that separated them from impending doom. It wouldn’t last long.

This is oversimplifying things, of course. There was also some fuss about the water-cooled, multi-valve heads Porsche was using on the 956s’ powerplants, and their twin turbochargers, to which IMSA seemed to object on entirely arbitrary grounds, knowing all too well what was in store for them if they didn’t. Porsche’s workarounds were simple: The 962 was basically a stretched 956 with an air-cooled, 12-valve, single-turbo motor ported over from the already demonstrably legal 935. The result was something Derek Bell today calls “more of a driver’s car,” delivering power more dramatically than its silkier European cousins. In the hands of Bell and Al Holbert, it went on to score five victories in its first season stateside. The contagion was global.

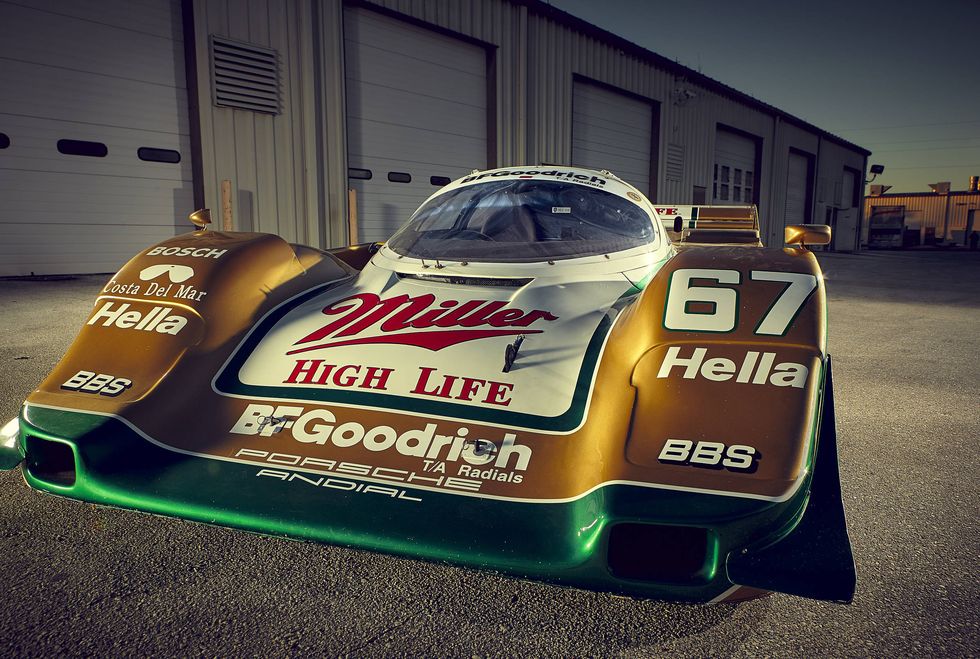

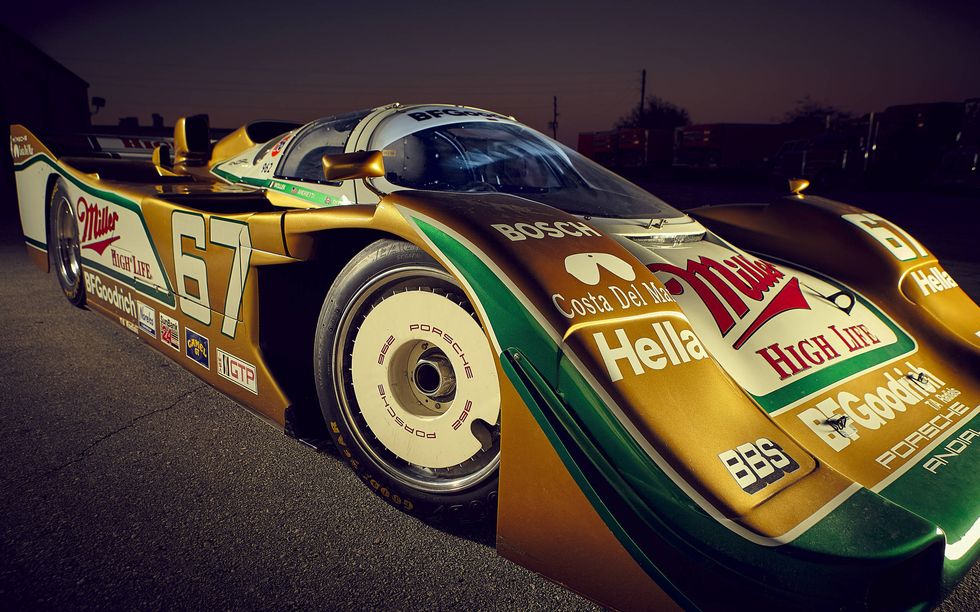

For Daytona in 1985, Jim Busby Racing brought its own pair of 962s, chassis Nos. 106 and 108. The BF Goodrich No. 67 car of Busby, Rick Knoop, and Jochen Mass finished third right out of the box, but its stablemate wasn’t so lucky: 107 laps into its career, having just pitted under caution for gas and tires, Pete Halsmer’s path was suddenly filled with a slower GTO entry. Halsmer would be fine; his car, not so much. The tub—Porsche’s first monocoque—was toast. A backup car was quickly sourced and readied in time for Sebring, and Busby Racing went on to its strongest season yet, collecting numerous podiums, including a 1-2 at

Meanwhile, back in San Clemente, down the road from Busby’s Laguna Beach workshop, a former Lola engineer named Jim Chapman set to work on an improved aluminum honeycomb tub for the wounded 962-108, while up in the valley in Van Nuys, Ed Pink, an old Beach Boys associate, was busy reverse-engineering the fussy Motronic fuel injection system’s read-only memory chips in order to get around Bosch’s boost, spark and fuel settings. By the time he was done, the hot-rodded Porsche was sending a gargantuan 850 hp to the wheels—200 more than the factory-supplied engine.

Returned to the fold for the 1987 season, the newly christened 962-108B ran strong all year, until disaster struck again, this time at

Sports dynasties are funny things. Impressive in retrospect, they’re not always that fun for the people living through them. It’s all a matter of perspective. I was three when Porsche’s mighty 917s basically put Can Am out of business, and those cars seem utterly bad-ass to me; these days, in my forties, Audi winning practically everything for ten years goes by so quickly that I don't even notice. “Hey, good for them!” I think.

For this writer, though, those years between 1982 and 1988 when 956s and 962s held the globe in their Teutonic tentacles—those six consecutive Le Mans victories, five wins at Daytona, five World Sportscar Championships, five Japanese sports car championships, three IMSA championships, ninety-one cars in total amassing countless victories and podiums between them—bracketed precisely the dawning of my interest in cars and racing and the moment when that obsession would be set aside for more immediate concerns related to finding one’s way in life. At an age when the beginning of a school year felt like embarking on an oceanic journey of incomprehensible proportions, when it was impossible to even imagine the person you’d be when you arrived on the other shore, these seasons felt interminable, and the Porsches’ stranglehold on the automotive world all the more suffocating.

I was there at Riverside in 1985 when the Busby Porsches finished first and second. I was there in 1986 when they finished second to the Holbert/Bell Lowenbrau car, 962s taking the first four spots. My friends and I rooted for anything but Porsches: Ford Probes, Corvette GTPs, and especially the achingly beautiful V12-powered Bob Tullius Group 44 Jaguars. It must have been one of the greatest moments of my young life in 1987 when the XJR-7 of Hurley Haywood and John Morton finally triumphed over our collective nemeses, finishing ahead of no fewer than four 962s (including the Busby 962-108B car in third), but to be completely honest I don’t even remember it. All I remember is the Porsches winning, and everyone else losing. Over and over and over again.

By just before six in the morning, the fog had cleared enough for the race to resume. If Derek Bell was pleased, it was only because he was that much closer to his workday being over. “I hate the things,” he said before the start of the now-23-hour ’89 contest in which he was embroiled. “I think they’re the most antisocial races God ever created.” At loose ends following the death of friend and teammate Al Holbert in a plane crash months earlier, Bell found himself teamed with a fellow veteran, Bob Wollek, himself a former Le Mans class winner and overall winner at Daytona (twice), and a relative newcomer, John Andretti, CART hopeful and Mario’s nephew, who, yes, a week earlier had been busy drifting a midget around the Hoosier Dome (he finished fourth).

This was the team Jim Busby had assembled for his latest attempt to crack Daytona, piloting his single entry, the old 108 car, now officially listed in its third incarnation as 962-108C—a bastard phoenix rising once more from the Weissach laboratories and the speed shops of Southern California to face off with its impossibly younger, fresher, fitter Nissan and Jaguar rivals. When the race resumed, it was just the three of them, really.

Just after 10 in the morning, having led for most of the previous 11 hours, the Nissan faltered with a dropped valve, allowing the Price Cobb–led Jag to move into first. For the next four hours, the Jaguar and Porsche swapped the lead with every pit stop, but ultimately it was Wollek in the 962 who held on at the end to cross the line 1:26 ahead of the Walkinshaw team, the closest margin in Daytona history. It was the Porsche 962’s 50th win in six years.

Wearing the Miller livery in which it finally delivered Jim Busby his first Daytona victory, Porsche 962-108C is slated to cross the block this month at Mecum’s Monterey auction. Like George Washington’s proverbial axe, it’s a little hard to say what remains of the original car beyond the serial number: As it exists today, it is arguably more a product of Orange County and San Fernando Valley than it is of Baden-Württemberg. Sacrilege? Not to Busby’s mind. He sees it as perfectly in line with a long Porsche tradition of being, as he sees it, the “coolest hot-rod outfit in town.”

It’s an unexpected comment, coming from a guy who cut his teeth on Colorado Boulevard. But for Busby, there’s a direct philosophical link between the resourcefulness of kids building ’32 Fords and Porsche’s habit of tinkering with existing designs long beyond the point when anyone else would be reaching for a clean sheet of paper.

Recalling his first trip to Weissach, in 1982, he says, “They’re showing me airplane motors they make out of 911 motors and all this cool stuff, and I’m thinking this is hot-rod heaven. It just reminded me of being in (SoCal) in the ’50s. You know, guys going, ‘Just take that over there and make it into this.’ ... And they still do it! They’re the ultimate hot-rodders.”

This article originally appeared in the August 8, 2016 issue of Autoweek magazine. Subscribe here.