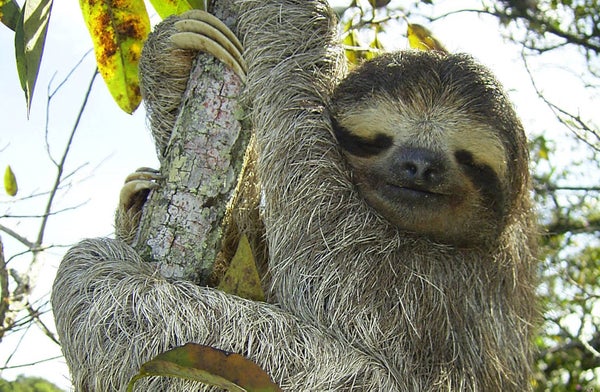

Three-toed sloths (Bradypus variegatus) are the slowest mammals on Earth, according to scientists who have spent 15 years studying these lazy tree-dwellers.

When it comes to saving energy, three-toed sloths are on a league of their own—panda bears, koalas and opossums can’t beat them—according to a research paper by Jonathan Pauli and Zachariah Peery, of the University of Wisconsin–Madison. “We really expected them to have low metabolic rates, but we found them to have tremendously low energy needs—much lower than their cousins, the two-toed sloths, and the lowest documented for any mammal,” Pauli says.

To reach this conclusion, the scientists measured the metabolic rates of 10 three-toed and 12 two-toed sloths in Costa Rica and compared the results with similar studies of 19 other species of arboreal folivores.

On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

With a field metabolic rate of 162 kilojoules per day per kilogram, the three-toed sloths have lower energy needs than koalas (Phascolarctos), which require 410 kilojoules per day per kilogram. Howler monkeys (Alouatta) need 583 and two-toed sloths, meanwhile, have an energetic expenditure of 234. Giant pandas are the only animals that come close on the heels of the three-toed sloths in the race for the title of slowest mammal—they consume 185 kilojoules per day per kilogram.

According to the study, published in the August issue of The American Naturalist, there is a suite of behavioral, physiological and anatomical adaptations that allow sloths to lead easy lives with minimum energy expenditure in the jungle canopies of Central and South America, but two aspects stand out:

The first is the parsimony with which they live, which suggests that laziness is not a cardinal sin, but an evolutionary trait. “Three-toe sloths have very small home ranges. They spend the vast majority of their time in the canopy of trees eating or resting or sleeping, so there are behavioral things that they do to limit the amount of energy they spend,” Pauli says.

The second is the ability of these gentle mammals to adjust their body temperatures by tweaking their internal thermostats. “They're slightly heterothermic they can fluctuate their body temperature about 5 degrees Celsius, in line with the outside temperature. By relaxing their body temperature, they have big savings in terms of their energetic output,” Pauli says.

Two-toed sloths—which seceded from their three-toe cousins in the phylogenetic tree about 20 million years ago—are not as efficient in adapting their body temperatures and have more active lifestyles because they feed from a wider variety of trees, and sometimes snack on small mammals.

Both species fascinate Pauli, who specializes in mammalian ecology and conservation, and studies sloths in an area about 85 kilometers northeast of Costa Rica’s capital, San Jose.