Visual perception begins with our retinas locating the edges of objects in the world. Downstream neural mechanisms analyze those borders and use that information to fill in the insides of objects, constructing our perception of surfaces. What happens when those borders—the fundamental fabric of our visual reality—are tweaked? Our internal representation of objects fails, and our brain's ability to accurately represent reality no longer functions.

Seemingly small mistakes lead to the very distorted perceptions of an illusory world.

PLUMB CRAZY

On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

PETER BENNETTS (top); SCIENTIFIC AMERICAN MIND (bottom)

No, the architects of this building were not drunk at the drawing board. In fact, the structure is perfectly rectilinear in every way. No slants, no tilts and no curves: just good old traditional 90-degree angles at work here. Australian architectural firm ARM Architecture based the façade design at the Port 1010 building in Melbourne on a famous bit of visual trickery known as the café wall illusion, popularized by the late vision scientist Richard Gregory of the University of Bristol in England. Mark McCourt, a vision scientist at North Dakota State University, has shown that the positions of the black-and-white bricks invoke a reverse contrast effect called brightness induction, which results in the mortar having the appearance of a twisted cord. Vision scientist and illusion creator Akiyoshi Kitaoka of Ritsumeikan University in Japan has further demonstrated this effect in minimalist fashion by isolating it to a single row of mortar with blocks. The alternation of black-and-white brick positions results in an alternating direction in the twisted cords of the mortar. The brain interprets these cords as being slightly tilted depending on the direction of the twist.

BUILDING THE IMPOSSIBLE, ONE LEGO AT A TIME

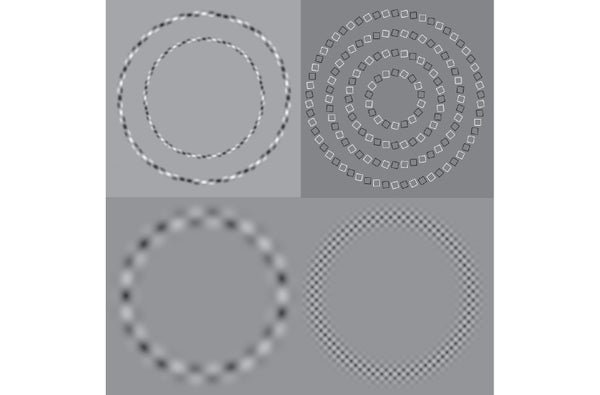

ADAPTED FROM A BULGE, BY AKIYOSHI KITAOKA; COURTESY OF MARY COFFELT, BRIENA HELLER AND MICHAEL MCCAMY

Don't believe any of this so far? Think it's all a bunch of camera tricks? Well, you don't have to take our word for it. Go to a Lego store and buy a baseplate that is at least 43 × 43 studs in size, 946 one-by-two tiles (554 black and 392 white), 196 one-by-one tiles (half black, half white), and 240 individual studs (half black, half white). You can then make your own Lego version of A Bulge, by Kitaoka. The version below uses purple and white Legos, with M&Ms instead of studs.

To see the illusion disappear with a single breath, watch this video at www.youtube.com/watch?v=QKCSBkdEUXQ

TWISTED SISTER

PASCAL LE SEGRETAIN Getty Images

Makeup enhances attractive facial features while hiding the undesirable. Now there is an outfit to accomplish the same illusory feat for your body. Actor Kate Winslet's dress, created by British fashion designer Stella McCartney, uses contrasting shapes to accentuate hips and shoulders and otherwise highlight the female form. For maximum effectiveness, be sure to wear it only in front of a black background.

TEETER-TOTTER SEESAW

SCIENTIFIC AMERICAN MIND

Spatial distortions can be measured for their power to alter perception. The seesaw at the top seems to tilt to the right, although, in fact, it is not tilting at all. If we remove the twisting candy-cane stripes from within, we now see the veridical planks and their untilted truth. A clever variant of this illusion, with a physically tilted plank that appears level through illusory means, reveals that the illusion is equivalent, perceptually, to as much as a four-degree actual tilt.

A nice animated version of the effect is at www.moillusions.com/2009/02/slanted-seesaw-optical-illusion.html