Editor’s note: In this excerpt from his essay ‘In Search of Tolerance’ Salil Tripathi writes on why tolerance is a necessity and not just a virtue.

The central flaw in the debate around tolerance is the assumption that tolerance is a desirable virtue. If anything, by calling tolerance a virtue, we make virtue of a necessity. Tolerance is necessary. Without tolerance, a society would be at perpetual war with itself, because the alternative of tolerance is intolerance, and sustained intolerance can eventually lead to violence.

Tolerance is an adequate response to what is unfamiliar; it is not an ideal state nor a desired one. In the Indian languages I know—Gujarati, Hindi, Marathi and Bengali—tolerance translates as sahanshilta, sahishnuta or shohho, words that indicate endurance or sufferance—these are necessary traits but they aren’t necessarily pleasant. Tolerance implies that the one with power—a king, a government or a majority—allows others to live their lives the way they wish; the underlying assumption being that there are markers not to be crossed, and those markers may not be defined. Tolerance also means acceptance, or submission, to the will of that ruler, the government or the majority. Here, the ones without power go along and comply, because the consequences would not be pleasant.

Mohandas Gandhi understood the critical difference between a virtue that was inclusive and one that was patronizing. In a series of lectures called ‘Ashram Vows’, Gandhi replaced sahishnuta as a vow with the idea of sarva dharma sama bhava. He said:

Sahishnuta is the translation of the English word, tolerance. I did not like that word, but could not think of a better one. Kakasaheb (Kalelkar) too did not like that word. He suggested ‘respect for all religions’. I did not like that phrase either. Tolerance may imply a gratuitous assumption of inferiority of other faiths to one’s own and respect suggests a sense of patronising, whereas ahimsa teaches us to entertain the same respect for the religious faiths of others as we accord to our own, thus admitting the imperfection of the latter.

While Gandhi was a deeply religious man, he was also a humanist, and he would have extended the same courtesy to those who doubt faith, the agnostics, and those of no faith, the atheists.

It is instructive that the British writer E.M. Forster called tolerance a ‘dull’ virtue. He was speaking in the context of the Second World War. In that wartime address, he pragmatically said, ‘It merely means putting up with people, being able to stand things. No one has ever written an ode to tolerance, or raised a statue to her.’ To build a civilized future, tolerance is the first block—that does not make tolerance an end goal. In his address, Forster cited Ashoka, Erasmus, Montaigne, Locke and Goethe as rulers and thinkers who saw the peril that lay ahead in a world driven by passion, and urged people to step away from the fervour of fanatics and outrage manufacturers of their time, and cultivate tolerance, so that we speak in a civil tone and learn to accept, respect, live and let live.

Indians have always been tolerant, just as Indians have always been intolerant. Indians have tolerated colonial powers, despots, sluggish economic growth, poor service, inequality, uncollected garbage, appalling air quality, books being banned, corrupt bureaucracy, slow courts, the hounding of lovers of different castes or faiths, and laws on statute books that outlaw same-sex relationships. Indians have also shown intolerance over bizarre slights, such as attacked the homes of cricketers when they lost matches, burned effigies of politicians and movie stars, vandalized buses and public property when something they disapproved of happened, and filed sedition cases against individuals they disagree with. The irony over the recent controversy, when a family was hounded out of a cinema hall because they did not stand up when the anthem was played, is acute: Rabindranath Tagore, who wrote the national anthem, had actually decried rabid nationalism in three fine essays, and in Ghare Baire (The Home and the World) he was deeply troubled by rabid nationalism—think of Nikhil’s disquiet over Sandip’s chest-thumping rabble-rousing.

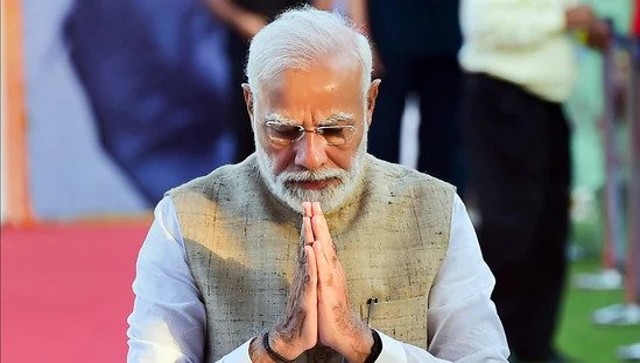

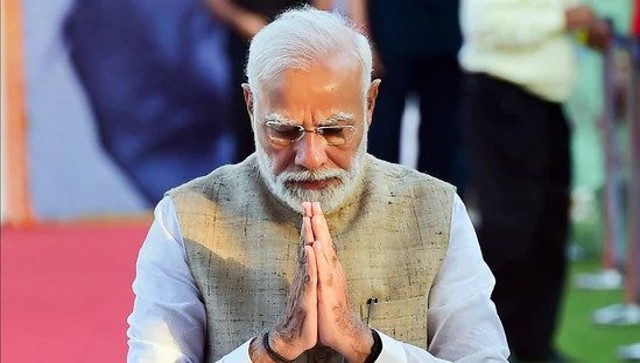

There is no grand conspiracy to call India intolerant, and nor can tolerance be switched on or off after an election result. Mood takes time to change; what an election outcome does is to signal what is acceptable behaviour. If the prime minister looks the other way when a minister says something ridiculous about minorities, the impact is rarely immediate. Riots are a lagging indicator and dangerous speech is a leading indicator. What the prime minister says in response to a murder, an act of lynching, or a vituperative tirade sets the tone for others, because it tells others what is permissible and what isn’t. There is nothing contrived about the protests from writers. It is just that when Nayantara Sahgal spoke up, it became the tipping point. And when people as unconnected as Sahgal, Keki Daruwalla, Krishna Sobti, Raghuram Rajan, Narayana Murthy, Shah Rukh Khan and Aamir Khan feel compelled to speak out, openly expressing apprehension, the nation needs to pause and reflect.

The debate over whether there is more intolerance now than two years ago is academic. Whether there were more riots in 2013 than in 2015 does not mean much to the family of Dr Kalburgi, the Kannada scholar who was murdered in August 2015. Mohammad Akhlaq’s widow won’t feel better if she is told that riots were more prevalent under the previous administration. Given India’s poor record in protecting minorities, and given the fact that the Congress party ruled India for fifty-five of its sixty-eight years of independence, it is hardly surprising to discover that more people died in rioting under Congress rule than under non-Congress rule. That fact is as irrelevant as telling people that if they lived in another country they would have been worse off.

Irony dies when someone like Aamir Khan is intimidated for expressing an opinion that his wife feels insecure. Telling him that he should be grateful that Indians have made him a superstar has an unstated corollary: enjoy what you have, don’t ask for more. ‘Yeh dil maange more’ is only an advertising slogan, and advertisements are embellishments, not reality. ‘Please, sir, I want some more,’ asked Oliver Twist in Charles Dickens’s classic eponymous novel. The master of the workhouse hit him with the ladle and shrieked: ‘Do I understand that he asked for more, after he had eaten the supper allotted by the dietary? That boy will be hung.’

That ‘more’ that the heart yearns for need not be love— that would require civilizational transformation. That ‘more’ is respect for his dignity. By insulting authors who return awards, actors who question the direction of the country, and executives who express concern over the economic consequences of bigotry, supporters of the government—and indeed some of its ministers—want to eliminate dissenting views. One people, one nation, under one leader, marching together—we know where such thinking originated, and where it can lead.

Excerpted from ‘Words Matter: Writings against Silence’ with permission of Penguin Books India

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)