OPINION:

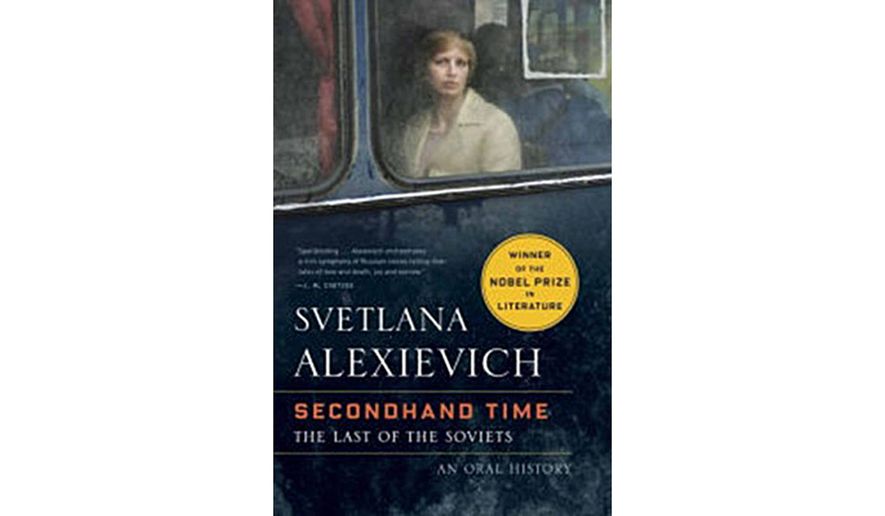

SECONDHAND TIME: THE LAST OF THE SOVIETS

By Svetlana Alexievich

Translated by Bela Shayevich

Random House, $30, 470 pages

“Freedom had materialized out of thin air,” writes Nobel Laureate Svetlana Alexievich of the 1991 collapse of the Soviet Union. “Everyone was intoxicated by it, but no one had really been prepared . We’d be just like everyone else. We thought that this time, we’d finally get it right.”

If only.

But it takes more than the death of old tyranny to give birth to new freedom. Hell had merely frozen over. A quarter of a century later, if anything is thawing out of the ice, it is the old Russian tradition of an authoritarian state. Not only does Vladimir Putin frequently wax sentimental about the lost Soviet empire; he has also reportedly put up a portrait of Czar Nicholas I, the most militarist, reactionary of 19th-century Romanovs, in his Kremlin offices. Far from getting it “right,” today’s post-Soviet Russia is run by a regime that combines many of the most noxious characteristics of both its Communist past, which lasted less than a century, and its czarist predecessor, going back to the medieval Duchy of Muscovy.

All of which lends considerable poignancy to the bruised, battered and often broken lives depicting themselves in the conversational shards collected by Ms. Alexievich, an oral historian some critics have compared with America’s Studs Terkel. Consider the following snippet from a conversation the author had with her own late father:

“He claimed that it was easier to die in war in his day than it is for untried boys to die in Chechnya now. In the 1940s, they went from one hell to another. Before the war, my father had been studying at the Minsk Institute of Journalism. He would recall how often, returning to college after vacations, students wouldn’t find a single one of their old professors because they had all been arrested.” They didn’t understand what was happening, she writes, “but whatever it was, it was terrifying. Just as terrifying as the war.”

Even as the Soviet police state watered down its violent tactics after the death of Stalin, it remained a weighty, often brutal defining presence in people’s lives. “I asked everyone I met what ‘freedom’ meant,” says Ms. Alexievich. “Fathers and children had very different answers.” Those born in the USSR and those born after its collapse “do not share a common experience — it’s like they’re from different planets.” For the fathers, freedom is “the absence of fear; the three days in August [1991] when we defeated the putsch.” For the children, freedom is “when you can live without having to think about freedom. Freedom is normal.”

Not yet, not there. At best, in today’s Russia, freedom is limited, conditional and subject to recall by the central authorities at any moment. Which may be why so many of the people Ms. Alexievich introduces us to sound a bit like wounded characters sleepwalking their way out of a play by Anton Chekhov. A striking example is the closing selection, the rambling reminiscence of a 60-year-old peasant “Everywoman”:

“These days they say we used to have a mighty fortress and then we lost it all. But what have I really lost? I’ve always lived in the same little house without any amenities — no running water, no plumbing, no gas — and I still do today. My whole life I’ve done honest work. I toiled and toiled, got used to backbreaking labor. And only ever earned kopecks. All I had to eat was macaroni and potatoes, and that’s all I eat today. I’m still going around in my old Soviet fur — and you should see the winters here!”

And then a little bit of Chekhovian whimsy — or Russian soul — pops up: “Have you seen my lilacs? I go out at night to look at them — they glow. I’ll just stand there admiring them. Here, let me cut you a bouquet …”

Like the lady with the lilacs, “Secondhand Time” is sometimes rambling, sometimes depressing, and sometimes uplifting — not so much a book of oral history as a brilliant pile of field notes. It could be better organized and better annotated, but its collective impact is tremendous and captures many different facets of life as lived in the Soviet Union and its successor states. Not the least disturbing impression is the way that some of the victims of terror, torture and persecution under the old order still look back on it with a certain masochistic nostalgia. One is reluctantly reminded of victims of child abuse who blame themselves for what happened, and sometimes even repeat the cycle of abuse as adults.

• Aram Bakshian Jr., an aide to Presidents Nixon, Ford and Reagan, writes widely on politics, history, gastronomy and the arts.

Please read our comment policy before commenting.