Extract from the book "Around India’s First Table: Dining and Entertaining at the Rashtrapati Bhavan" by Elizabeth Collingham.

The Indian Republic’s First State Banquet

On 24 January 1950 Indrani Jagjivan Ram attended her first state banquet at Government House, New Delhi. That morning the constituent assembly had signed India’s new constitution. On this symbolic occasion, the ‘palace’, which had been built as an emblem of British power, cast its aura of splendor over the meeting of the heads of two of the first Asian countries to throw off the yoke of colonial rule. Governor General Chakravarti Rajagopalachari was the first Indian to occupy the office after the British had departed in August 1947. His guest, President Sukarno of Indonesia, had led his country’s struggle for freedom. The Dutch had acknowledged Indonesia’s independence just one month previously, in December 1949. The Indonesian president had come to India to celebrate India’s first Republic Day.

Indrani and her husband were greeted at the guest entrance by two finely dressed ushers and directed along a corridor lined with the Governor General’s Bodyguard (GGBG), standing so still that they resembled lifeless statues. When they reached the Ashoka Hall they found a crowd of well-dressed guests milling about with butlers moving among them carrying trays of colourful sherbets in tiny glasses. A short while later a voice called, ‘Attention!’ everyone obediently formed a neat line. The band played the Indonesian national anthem, followed by the ‘Jana Gana Mana’ and Governor General Rajagopalachari and President Sukarno glided into the room. They moved along the line of guests, shaking hands and exchanging a few words with each of them on their way to the dining room.

Indrani was relieved to find herself seated next to the comfortingly familiar figure of Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru. He reassured her that the butler would only place suitable food before her as the rose next to her plate indicated that she was vegetarian. As the band began to play and everyone began to eat their cream of spinach soup, he explained how the proceedings worked: ‘See those tiny green and red bulbs on the wall in front of you – when each course commences the green bulb will be on and the bearers will start to serve the food. And when the course finishes, the red light will flash, signaling bearers to start clearing up the table. See now the red light is on, now the bearer will take the plates away.’ Indrani listened politely but asked herself for how long were Indians going to be proud of adopting British manners now that the departure of the British meant the end of India’s slavery.

In fact, what Indrani was witnessing was not so much an act of imitation but of appropriation. Walking in the grounds of the magnificent building when it was still the Viceroy’s House, Gandhi had told the viceroy, Lord Mountbatten, that it was far too big for one man. It would have to be turned into a museum or college once the British had finally departed. Mountbatten protested that India would be the largest democracy in Asia. The eyes of the world would be upon her. Other heads of state would come and visit and India would need to entertain and impress them. This was precisely the way in which the new Indian prime minister and his governor general were using the house in January 1950. The cloak of splendor which the house had thrown over the Raj was now being used to lend grandeur to the new Indian Republic. In fact, Indrani’s husband, Jagjivan Ram, was the youngest minister in Nehru’s interim cabinet. In those early days, just two years after independence, the principal aim was to demonstrate that the Indian state had mastered, and could effectively deploy, the conventions that governed state occasions. India was not simply aping viceregal rituals, but showing it was fluent in the diplomatic language of state protocol in which all nations needed to be conversant. The success of the banquet affirmed that India could proudly take its place on the international stage. Today, guests at a state banquet at the Rashtrapati Bhavan experience a ritual which echoes the viceregal past but which the Indian state has quietly but emphatically made its own.

Guests arriving at the Rashtrapati Bhavan for a state banquet ascend to the main floor by means of a marble staircase which was designed as the viceroy’s private staircase. On either side of the staircase, troughs lined with black marble catch water which spouts from lions’ heads set on the walls. The President’s Bodyguard (PBG) lining the guests’ route look every bit as impressive as the motionless Sikh lancers who stood in the corridors like grim stone giants when the French socialite Baron Jean Pellene attended a viceregal ball in 1935.

The ceremony of greeting the President of India and his guests has been modified since the early days when Indrani experienced her first banquet. It is now the guests who walk up to the president after their name has been announced. The mode of entering the dining room has also been altered since the early days after Indian Independence. The guests now file in first. Once everyone is standing solemnly behind their chairs, the President of India and his guests of honour walk to their places along the space between the table and the chairs. Only once the president has taken his seat at the centre of the table does everyone else sit down. Political precedence is still carefully observed, just as it was in the days of the Raj, with the president at the apex of the triangle and the guests ranged along the table in order of their place in the political hierarchy.

Also read: All the President's books

Also read: A Q&A with Elizabeth Collingham, author of "Around India’s First Table: Dining and Entertaining at the Rashtrapati Bhavan"

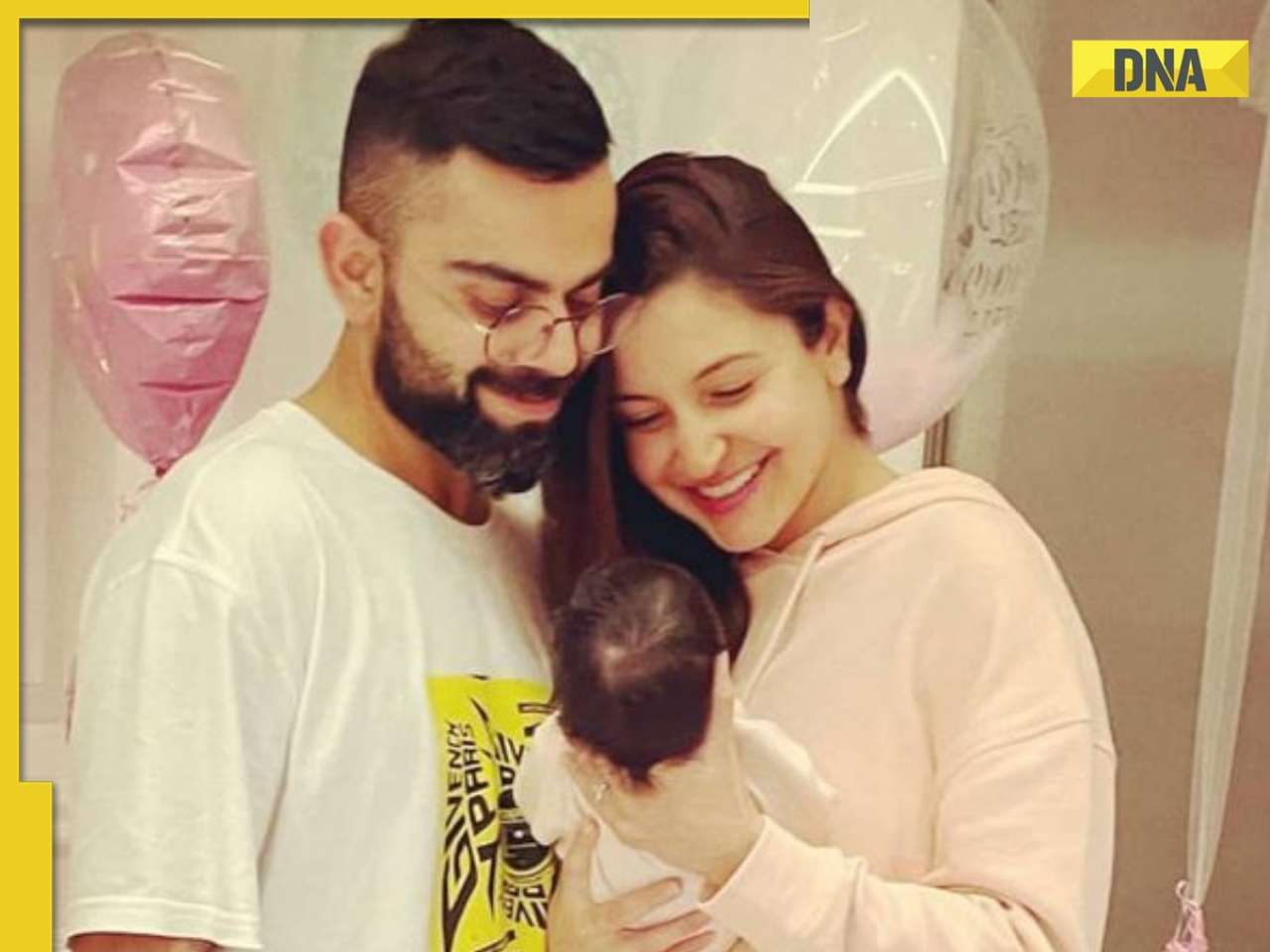

![submenu-img]() Anushka Sharma, Virat Kohli officially reveal newborn son Akaay's face but only to...

Anushka Sharma, Virat Kohli officially reveal newborn son Akaay's face but only to...![submenu-img]() Elon Musk's Tesla to fire more than 14000 employees, preparing company for...

Elon Musk's Tesla to fire more than 14000 employees, preparing company for...![submenu-img]() Meet man, who cracked UPSC exam, then quit IAS officer's post to become monk due to...

Meet man, who cracked UPSC exam, then quit IAS officer's post to become monk due to...![submenu-img]() How Imtiaz Ali failed Amar Singh Chamkila, and why a good film can also be a bad biopic | Opinion

How Imtiaz Ali failed Amar Singh Chamkila, and why a good film can also be a bad biopic | Opinion![submenu-img]() Ola S1 X gets massive price cut, electric scooter price now starts at just Rs…

Ola S1 X gets massive price cut, electric scooter price now starts at just Rs…![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Is CAA an anti-Muslim law? Centre terms news report as 'misleading'

DNA Verified: Is CAA an anti-Muslim law? Centre terms news report as 'misleading'![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Lok Sabha Elections 2024 to be held on April 19? Know truth behind viral message

DNA Verified: Lok Sabha Elections 2024 to be held on April 19? Know truth behind viral message![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Modi govt giving students free laptops under 'One Student One Laptop' scheme? Know truth here

DNA Verified: Modi govt giving students free laptops under 'One Student One Laptop' scheme? Know truth here![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Shah Rukh Khan denies reports of his role in release of India's naval officers from Qatar

DNA Verified: Shah Rukh Khan denies reports of his role in release of India's naval officers from Qatar![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Is govt providing Rs 1.6 lakh benefit to girls under PM Ladli Laxmi Yojana? Know truth

DNA Verified: Is govt providing Rs 1.6 lakh benefit to girls under PM Ladli Laxmi Yojana? Know truth![submenu-img]() In pics: Rajinikanth, Kamal Haasan, Mani Ratnam, Suriya attend S Shankar's daughter Aishwarya's star-studded wedding

In pics: Rajinikanth, Kamal Haasan, Mani Ratnam, Suriya attend S Shankar's daughter Aishwarya's star-studded wedding![submenu-img]() In pics: Sanya Malhotra attends opening of school for neurodivergent individuals to mark World Autism Month

In pics: Sanya Malhotra attends opening of school for neurodivergent individuals to mark World Autism Month![submenu-img]() Remember Jibraan Khan? Shah Rukh's son in Kabhi Khushi Kabhie Gham, who worked in Brahmastra; here’s how he looks now

Remember Jibraan Khan? Shah Rukh's son in Kabhi Khushi Kabhie Gham, who worked in Brahmastra; here’s how he looks now![submenu-img]() From Bade Miyan Chote Miyan to Aavesham: Indian movies to watch in theatres this weekend

From Bade Miyan Chote Miyan to Aavesham: Indian movies to watch in theatres this weekend ![submenu-img]() Streaming This Week: Amar Singh Chamkila, Premalu, Fallout, latest OTT releases to binge-watch

Streaming This Week: Amar Singh Chamkila, Premalu, Fallout, latest OTT releases to binge-watch![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: What is Israel's Arrow-3 defence system used to intercept Iran's missile attack?

DNA Explainer: What is Israel's Arrow-3 defence system used to intercept Iran's missile attack?![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: How Iranian projectiles failed to breach iron-clad Israeli air defence

DNA Explainer: How Iranian projectiles failed to breach iron-clad Israeli air defence![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: What is India's stand amid Iran-Israel conflict?

DNA Explainer: What is India's stand amid Iran-Israel conflict?![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: Why Iran attacked Israel with hundreds of drones, missiles

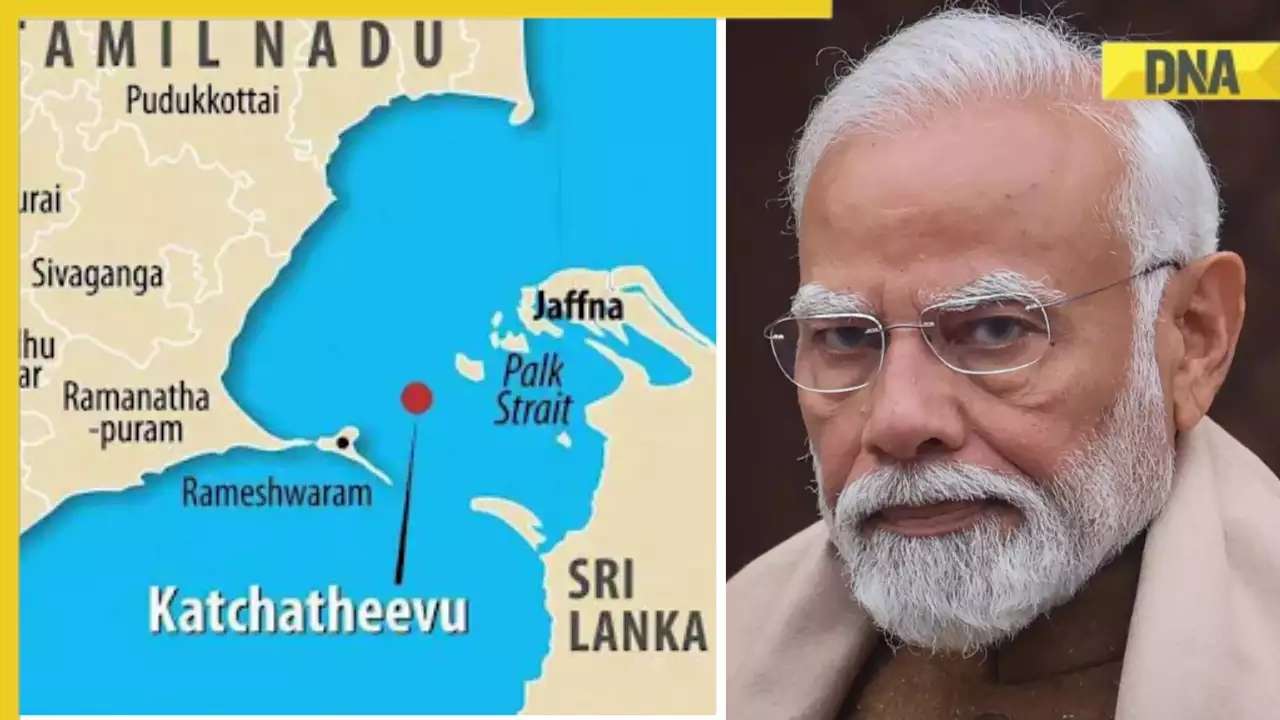

DNA Explainer: Why Iran attacked Israel with hundreds of drones, missiles![submenu-img]() What is Katchatheevu island row between India and Sri Lanka? Why it has resurfaced before Lok Sabha Elections 2024?

What is Katchatheevu island row between India and Sri Lanka? Why it has resurfaced before Lok Sabha Elections 2024?![submenu-img]() Anushka Sharma, Virat Kohli officially reveal newborn son Akaay's face but only to...

Anushka Sharma, Virat Kohli officially reveal newborn son Akaay's face but only to...![submenu-img]() How Imtiaz Ali failed Amar Singh Chamkila, and why a good film can also be a bad biopic | Opinion

How Imtiaz Ali failed Amar Singh Chamkila, and why a good film can also be a bad biopic | Opinion![submenu-img]() Aamir Khan files FIR after video of him 'promoting particular party' circulates ahead of Lok Sabha elections: 'We are..'

Aamir Khan files FIR after video of him 'promoting particular party' circulates ahead of Lok Sabha elections: 'We are..'![submenu-img]() Henry Cavill and girlfriend Natalie Viscuso expecting their first child together, actor says 'I'm very excited'

Henry Cavill and girlfriend Natalie Viscuso expecting their first child together, actor says 'I'm very excited'![submenu-img]() This actress was thrown out of films, insulted for her looks, now owns private jet, sea-facing bungalow worth Rs...

This actress was thrown out of films, insulted for her looks, now owns private jet, sea-facing bungalow worth Rs...![submenu-img]() IPL 2024: Travis Head, Heinrich Klaasen power SRH to 25 run win over RCB

IPL 2024: Travis Head, Heinrich Klaasen power SRH to 25 run win over RCB![submenu-img]() KKR vs RR, IPL 2024: Predicted playing XI, live streaming details, weather and pitch report

KKR vs RR, IPL 2024: Predicted playing XI, live streaming details, weather and pitch report![submenu-img]() KKR vs RR IPL 2024 Dream11 prediction: Fantasy cricket tips for Kolkata Knight Riders vs Rajasthan Royals

KKR vs RR IPL 2024 Dream11 prediction: Fantasy cricket tips for Kolkata Knight Riders vs Rajasthan Royals![submenu-img]() RCB vs SRH, IPL 2024: Predicted playing XI, live streaming details, weather and pitch report

RCB vs SRH, IPL 2024: Predicted playing XI, live streaming details, weather and pitch report![submenu-img]() IPL 2024: Rohit Sharma's century goes in vain as CSK beat MI by 20 runs

IPL 2024: Rohit Sharma's century goes in vain as CSK beat MI by 20 runs![submenu-img]() Watch viral video: Isha Ambani, Shloka Mehta, Anant Ambani spotted at Janhvi Kapoor's home

Watch viral video: Isha Ambani, Shloka Mehta, Anant Ambani spotted at Janhvi Kapoor's home![submenu-img]() This diety holds special significance for Mukesh Ambani, Nita Ambani, Isha Ambani, Akash, Anant , it is located in...

This diety holds special significance for Mukesh Ambani, Nita Ambani, Isha Ambani, Akash, Anant , it is located in...![submenu-img]() Swiggy delivery partner steals Nike shoes kept outside flat, netizens react, watch viral video

Swiggy delivery partner steals Nike shoes kept outside flat, netizens react, watch viral video![submenu-img]() iPhone maker Apple warns users in India, other countries of this threat, know alert here

iPhone maker Apple warns users in India, other countries of this threat, know alert here![submenu-img]() Old Digi Yatra app will not work at airports, know how to download new app

Old Digi Yatra app will not work at airports, know how to download new app

)

)

)

)

)

)

)