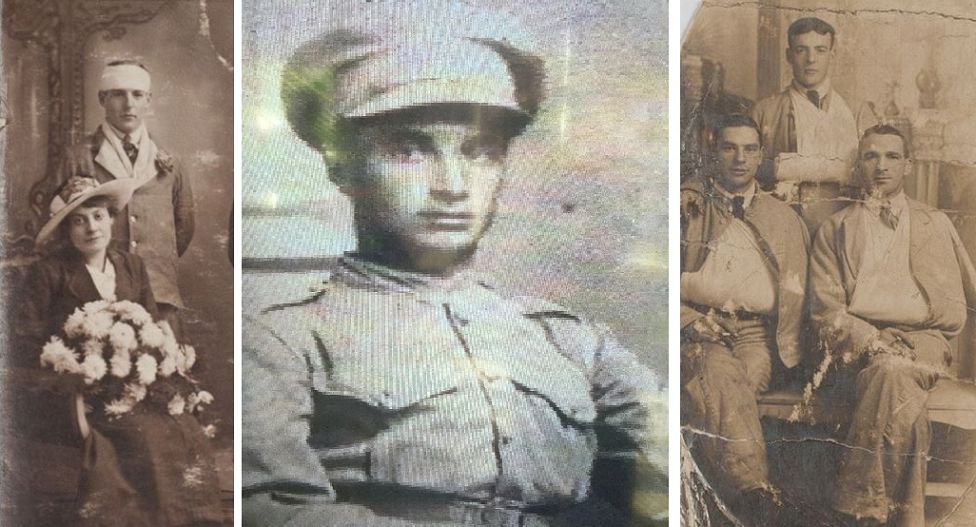

The World War One soldiers who came back from the dead

- Published

Households in World War One would await the telegraph boy's knock with a cold fear. Worlds were ripped apart with a few brief words announcing a serviceman's death, with follow-up letters from commanding officers rarely filling in enough of the blanks. But some families went through needless heartbreak. Sons, brothers and fathers were reported dead when they were very much alive.

One of those was Pte Fred Joslin, who was 19 when he was "killed" in machine gun fire. His mother heard from the War Office and there had already been a church service in his memory when he wrote home from a hospital in Malta.

How did these mix-ups happen?

Sometimes comrades genuinely thought a fellow soldier was dead when in fact he was injured. This is what happened to Pte Joslin - who eventually lived to the age of 95.

In his memoirs Pte Joslin, who lived in the Essex village of Terling, said: "I was hit by a burst of machine gun fire and thrown very forcibly to the ground where I lay on my stomach. The blood from my wounds in the back and shoulder ran around my ears.

"It appeared to those seeing me that the blood was coming from my ears and experience had proved that wounded soldiers bleeding from the ears had little chance of survival."

He was paralysed - and the next day a lost British major heard him shouting and rescued him.

His mother was "shell-shocked" by receiving a letter apparently from her dead son - and since the handwriting was that of a nurse Fred had dictated his words to, rather than in his own script, even the War Office wouldn't accept Pte Joslin was alive.

Good luck charms

Pte Joslin's son Peter, a former chief constable of Warwickshire Police, said his father's death notification had hung over their mantelpiece for years.

"The biggest problem was that it took so long before the government would accept the fact that he was alive.

"His mother was wondering what on earth had happened, because he was in hospital in another country and had to ask a nurse to write for him."

As soon as the injured solider had recovered he was sent back to the front line, so did not immediately return home to be reunited with his family and friends who had thought he was dead, Mr Joslin, from Kenilworth, said.

There were also cases of mistaken identity, says historian David Bilton, who wrote about the subject in Reading in the Great War 1914-1916 and Vol II, 1917-1919.

"Soldiers used to exchange items with their best friends when they were going over the top as good luck charms. They would wear one another's identity bracelet, or give each other their last letter home.

"Survivors who recovered bodies from the battleground would look for property on the body to identify them.

Alfred Holland

In 1914, Pte Alfred Holland's wife received a telegram from the War Office and a letter of sympathy from Lord Kitchener.

Her husband, from Reading, Berkshire, had taken out a life insurance policy which immediately paid his "widow" £25.

A later telegram confirmed that he was recovering from wounds at a prisoner of war camp in Germany. The insurance company did not ask for a refund.

Another confusion was when soldiers were taken prisoner of war and although the Germans were supposed to send back paperwork to say so, it often didn't happen, so a War Office letter went home saying they were missing and later presumed dead.

"Some prisoners of war were kept in France and Belgium illegally as slaves close to the front line.

"The Germans couldn't admit it was happening so wouldn't fill in the paperwork," Mr Bilton says.

Sydney Deadman

The parents of the ironically named Pte Sydney Deadman, of Woodley, Berkshire received a notice from the war office in 1918 saying he had been killed in action.

A memorial service was held in Woodley Church and shortly afterwards they received a request for cigarettes from him.

He had written from a prisoner of war camp in Germany where he was recovering from wounds in both legs.

L/Cpl Fred Hardy was another soldier who rose from the dead. Injured, but alive, he returned home to his parents to find they'd received a handwritten note telling them of his death.

"He was hit by a sniper just below the eye," Capt Maurice Turner of the 1/4th Suffolk Regiment had written to L/Cpl Hardy's father.

"I am sorry to say he was conscious... but I am quite convinced he did not realise the gravity of his wound".

But L/Cpl Hardy survived and appeared to regard his death notification with pride or amusement, military historian Taff Gillingham says.

"He had the letter framed and hung on his wall, presumably as a reminder that reports of his death were greatly exaggerated."

Laurence Marriott

Laurence Marriott of the 41st Field Artillery had his name engraved on the Menin Gate Memorial to the Missing in Ypres, Belgium. He later turned up alive and well.

It turned out he was in an explosion at Hellfire Corner in the Ypres Salient - but his horse took the brunt of the blast. His identity tags were lost in the confusion and were found after he'd been moved. He was therefore presumed dead.

Once recovered, Marriott, from Sheffield, joined up for a second time. Wounded again, he was sent to recover in Bury, Greater Manchester where he met his wife Mary.