Modern campaigning can seem hopelessly technical. A life of public service now appears to require a postdoc in Snapchat, Pinterest and Bitcoin - the “Finnegan’s Wake” of currency.

But politics can also be downright primitive, a game the loudest voice wins.

It might be that the most significant technology of this rally-heavy 2016 US presidential election is the one first prototyped in 600 BC: the microphone.

With the microphone, amplifying a message like “Make America Great Again” does not depend on retweets, but on ancient materials such as copper, magnets and sintered bronze.

All this mined stuff expands the soundwaves made with good old flesh and capillaries, larynxes and lungs, so that those waves land resoundingly on sensitive eardrums, willing or not.

This is not software.

This is power exerted, mouth to ear, human body to human body, by way of metals and minerals.

From the weird Hannibal Lecter mouth-masks that bullhorned domineering voices through the amphitheatres of ancient Athens; to Edison’s carbon microphones, which debuted at the Metropolitan Opera in 1910; to the coveted Neumann u47 microphones used by Audible, The Beatles and Hitler, microphones have been the key to holding a room in awe.

Or a stadium.

Or Nuremberg.

In fact, monopolising the microphone may be a key to political success.

We typically attend to politician’s words - the “message” - but merely having the mic gives any message a shot.

And the bulk of mic-monopolising may be simply claiming a microphone to begin with - and fending off anyone else who comes for it.

One year ago, Hillary Clinton faced a crowd in New York with a bum mic; after much fumbling a new one was handed her - by her husband. The passing of the mic.

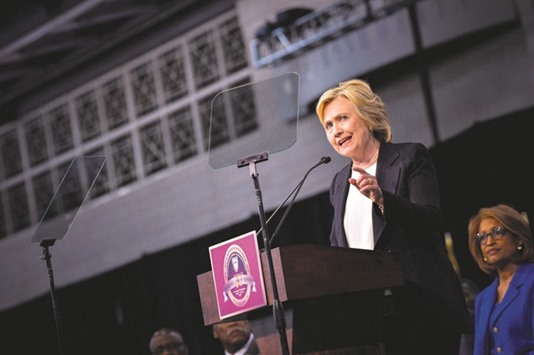

And although Clinton professes to prefer small unamplified gatherings to rallies, she’s managed to stay discreetly loud by choosing wireless and lavalier microphones that let her move closer to interlocutors, talkshow-style, without forfeiting her volume edge.

Even as these encounters look more egalitarian than a rally, Clinton’s clucks of sympathy are still the loudest sounds in the room.

The volume monopoly at political gatherings is crucial - and to challenge that monopoly is destabilising.

The most disruptive protesters at rallies this year have not been would-be assassins but would-be microphone-seizers.

In Seattle last summer, Bernie Sanders was cast into abjection and silence when protesters Marissa Johnson and Mara Jacqueline Willaford gained control of his podium and his mic.

In March, Thomas Dimassimo, a protester at a Donald Trump rally, planned to take Trump’s microphone and say “Donald Trump is a racist”. He was arrested before he got anywhere.

Trump is fiercely committed to his mic monopoly. At the podium, with a powerful multidirectional microphone squarely at chin level, he bellows while the crowd falls silent, their cheers reduced in the sound mix from a roar or incantation to a kind of hahhhh.

Some politicians (President Barack Obama, for one) like to listen, wait and grinningly bask in enthusiastic sounds from a crowd - “oh, go on” - but Trump can’t conceal his impatience to make his volume great again, even if that means hushing his supporters.

At a rally in Florida in January, Trump showed what he’d do to anyone who came for his mic. Interrupting his speech on the country’s plight, Trump turned to a problem closer at hand: “I don’t like this mic,” he said abruptly. “Whoever the hell bought this mic system - don’t pay the son of a b**** that put it in.”

He couldn’t stop: “Stupid mic keeps popping. Do you hear that, George? Don’t pay ‘em. Don’t pay ‘em. You know, I believe in paying, but when somebody does a bad job - like this stupid mic - you shouldn’t pay the bastard.”

Loudness, and his absolute entitlement to it, is even a staple of Trump’s rants to the press.

When asked by the Washington Post about his treatment of protesters at rallies, Trump dilated on a single demonstrator - one who had the temerity to try to be heard above Trump’s wall of sound.

“We’ve had some very bad people come in. We had one guy - and I said it - he had the voice - and this was what I was referring to - and I said, ‘Boy, I’d like to smash him.’ You know, I said that. I’d like to punch him. This guy was unbelievably loud. He had a voice like Pavarotti.”

Shouting battles sound petty - but they’re also elemental, politics at their simplest and rawest. After all, deafening vocal attacks on incompetent or immoral individuals are where politics started.

In the marketplace of ancient Athens, Plato raised his voice to harangue rich Greek mall-rats and compulsive shoppers. Did they have any idea what life’s even about? Sickos! That full-throated name-calling - as Plato did it - became what’s known as Western philosophy.

And politics.

The BC youth of Plato’s day gathered around to see those moneybags ponces dressed down, as later AD youth would cheer to hear Bernie Sanders rail against entitled bankers.

The candidate who manages to grab the Big Mic in November will, of course, have to take it from its current owner.

Other US presidents have been reluctant to give up their volume advantage, but in May Obama hinted he knew he couldn’t hold on forever. Saying goodbye at the White House Correspondents’ Dinner, he said he had just two words: “Obama out.” And with that, he dropped the mic.

*Virginia Heffernan’s new book is Magic and Loss: The Internet as Art.

Democratic presidential candidate Hillary Clinton speaking at an event in Philadelphia: although Clinton professes to prefer small unamplified gatherings to rallies, she’s managed to stay discreetly loud by choosing wireless and lavalier microphones that let her move closer to interlocutors, talkshow-style, without forfeiting her volume edge.