- India

- International

If we had maintained the momentum of 1991, we could have achieved much more: C Rangarajan

C Rangarajan was Deputy Governor of the RBI (1982-91), Planning Commission member (August 1991-December 1992) and later RBI Governor (December 1992-November 1997).

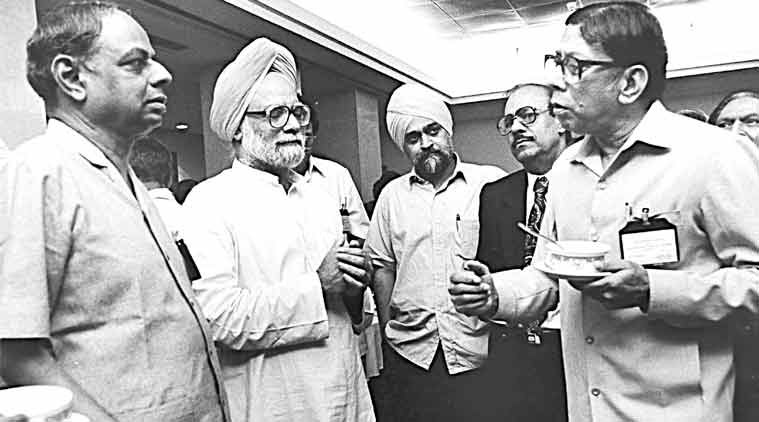

Then RBI governor C Rangarajan (far left) with Manmohan Singh and Montek Singh Ahluwalia at a meeting with the chief executives of banks in August 1995. (Express Archive)

Then RBI governor C Rangarajan (far left) with Manmohan Singh and Montek Singh Ahluwalia at a meeting with the chief executives of banks in August 1995. (Express Archive)

There is perhaps no one who would have straddled the pre- and post-reform period in India as much as Chakravarty Rangarajan, an influential member of Manmohan Singh’s team which implemented the economic reforms programme in the early 1990s. To start with, the former academic who once taught at IIM-Ahmedabad came straight to the RBI as a deputy governor in 1982. During Manmohan Singh’s tenure as RBI governor in the 1980s, he was a key member of the Sukhamoy Chakravarty committee whose recommendations formed the basis on which interest rates in India were later de-regulated. As deputy governor and member, Planning Commission, during the days of crisis management and reforms, he steered forex management while helping fashion a strategy for building and managing the country’s foreign exchange reserves in the backdrop of the 1991 balance of payments crisis.

It is as RBI governor that Rangarajan pitched for phasing out of automatic monetisation of the fiscal deficit, provided the direction for market-determined exchange rates and opened up the Indian banking sector. He also provided the intellectual foundation for a monetary policy focused on inflation control which has been followed by successive RBI governors, including Raghuram Rajan .

Later, he became governor of Andhra Pradesh and chairman of the 12th Finance Commission, following which he was appointed as Chairman of the PM’s Economic Advisory Council or PMEAC during Manmohan Singh’s tenure as prime minister. Speaking to The Indian Express, Rangarajan said that reforms must be part of a “continuing agenda” and that the country has to build on the momentum generated by earlier reforms. Edited excerpts:

[related-post]

Watch Video: What’s making news

What are the changes triggered by the 1990-91 crisis and how did the political establishment react?

The 1991 crisis compelled us to create a new framework in which the fundamental principle would be that competition is key to improving efficiency. Therefore, there has been a common thread running through the measures that have been implemented since 1991, which is to improve productivity by infusing competition. When we launched economic reforms, we were in serious negotiations with the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and the World Bank. They do have a certain approach and bias towards creating a more competitive environment. In some ways, the new policy framework was in sync with their views. It would, however, be wrong to suggest that we made those changes because of their insistence.

The enormity of the crisis (1991) left us with no alternative. Dr Manmohan Singh, as finance minister, spearheaded the new policy and it was Prime Minister Narasimha Rao who provided the political cover. In the first year of reforms, I was a member of the Planning Commission and Mr Rao, as chairman of the Planning Commission, had no difficulty going along with us on the new policy stance for the New Five Year Plan. Rao was not a reluctant reformer. He was fully behind all the measures taken. But he knew that the Congress party to which he belonged had a certain background. Therefore, he couched all reform measures in a language which could appeal to old-time politicians. So he used the word “middle path”. There was greater acceptance of the new policy stance as the measures started to have a favourable impact on the economy.

How did your role play out then?

The measures initially covered areas of fiscal policy, industrial policy, trade policy and foreign exchange management and were later extended to various sectors. During that phase of reforms, the exchange rate regime underwent a big change and became more or less market-determined, subject to interventions by the RBI. The elimination of the automatic monetisation of the fiscal deficit gave to the RBI the desired autonomy with regard to monetary policy… All important steps towards strengthening the banking system — licencing of private banks and amendment to the Nationalisation Act — made it possible for the government to reduce its stake. There was a burst of activity in the first few years after the 1991 balance of payment crisis. After the crisis receded, it became difficult to introduce reforms.

How different was the response to the 1991 crisis when compared to earlier ones?

The crisis itself was triggered by the balance of payments problem. Earlier, it was possible to find a solution (to such crises) by raising money… But in 1991, it was a recognition that such a crisis should not emerge again… What made us change was the severity of the problem. We had never been reduced to a situation where the foreign exchange available was enough to cover just three weeks of imports. We had never faced such a situation until then (1991) where we had to pledge gold.

More than two decades after opening up, what, according to you, remains closed and needs to be opened up?

For instance, many sectors which needed reforms — such as coal, power and telecom — have had to wait. It came, but in a slow and steady manner. If we had maintained the momentum, we could have achieved much more. Clearly, for instance, the monopoly of the government in coal production had its impact. The induction of the private sector has not been possible even today. The insurance sector also should have opened up much earlier. Financial sector reforms encompass an area beyond banking and in the insurance sector, as far as the private sector was concerned, the foreign investment cap was restricted to 26% and we could raise it to 49% only recently. Right from the start, we somehow had various sectoral caps for foreign investment and these have not been done away with even now.

What would you do if you were in a similar role now?

We need to carry forward the reforms introduced then. The changes contemplated in the new monetary policy framework is consistent with the dominant objective of the RBI — of price stability and a continuation of the earlier reform of doing away with automatic monetisation. There is a need to create a more competitive environment in the banking sector. The safety and soundness need to be enhanced. Some of the measures introduced in the 1990s need to be re-worked in the context of the present environment. On the forex side, we need to look at how the exchange rate moves, addressing the issue of volatility and also ensuring that the rupee’s Real Effective Exchange Rate or REER doesn’t appreciate much.

What are the policy measures or reforms that need to be carried out over the next 25 years?

We need to extract the full potential of the reforms we have already introduced. Besides, reforms must be part of a continuing agenda. The introduction of the Goods and Services Tax will help enhance efficiency. “Acquisition” is against the spirit of competition and the scope of any land acquisition Act must, therefore, be limited. At the same time, we should avoid fixing the price of their (farmers’) land. There are still segments of industry which are subject to a number of controls of the pre-1991 type. A typical example is the sugar industry with molasses subject to a type of control which results in subsidising the liquor industry. The basic principle of creating competitive markets with minimal barriers to entry should be extended to all sectors… Among the sectors that have remained untouched by reforms, the most important is agriculture. While much remains to be done to improve the productivity of agriculture through scientific research and improved dissemination of knowledge, there are areas such as marketing where reforms are badly needed. Barriers to movement of trade across the country must be brought to an end.

You mentioned areas which are still untouched by reforms. What about labour?

Flexible labour markets always help in generating faster growth. For example, in the post 2008 crisis period, the US has done better than Europe because of the more flexible labour markets there. Nevertheless, the time for modifying labour markets is when the economy is booming, that is, when the economy will be able to easily absorb the disruptions. Labour will then realise that it stands to gain more from a fast growing economy than by legislative constraints… Thus, while some reforms of the labour market are necessary; they should wait till the economy gathers momentum and moves on to a much stronger growth path.

More Explained

EXPRESS OPINION

Apr 26: Latest News

- 01

- 02

- 03

- 04

- 05