Co-authored by Dr. Elizabeth Stiles, Associate Professor of Political Science at John Carroll University.

Donald Trump's GOP primary victory took many pundits and political scientists by surprise. Many argued that his lack of fundraising, endorsements, and ground game would stop his momentum once people started voting. In hindsight, it is clear that these pundits and scholars too easily dismissed a key component of Trump's success: he was the one GOP candidate that people were paying attention to. Expanding beyond the 2016 GOP primary, does getting people to pay attention to a campaign help a candidate win a presidential primary?

Who Matters: The Public or the Elite?

To help answer this question, we look at a variety of factors that could help us understand why a candidate wins a presidential nomination. First, we include information about elite activities, such as endorsements and media attention. The impact of endorsements on presidential primaries was popularized by the influential book, The Party Decides, which argues that political elites - members of Congress, governors, and other political figures - signal their support for a candidate to the constituents and followers in their networks. When these elites coalesce behind a particular candidate early in the race, such as Al Gore (2000) or Bob Dole (1996), challenging candidates can be starved for cash and headlines.

But there are potential problems with this argument. Sometimes, party elites are unable to decide who to support. At other times, their preferred candidate is defeated. That is why we think that public attention (measured by Google search traffic) may be another way to explain who wins presidential primaries.

To test this hypothesis, we use a regression model incorporating the aggregate primary vote (APV) as the dependent variable. In addition to our elite and public attention measures, we include information on momentum (such as whether a candidate won in Iowa and/or New Hampshire) and fundraising.

The results demonstrate the importance of both elite endorsements and public attention in explaining a candidate's share of the APV. A one percent increase in a candidate's share of elite endorsements increases their APV by about one-third of a percent. Hillary Clinton's 2008 campaign is a good example of this - she received almost 62 percent of elite Democrat endorsements and took home a plurality of the APV. Among Republicans that same year, John McCain held a narrow endorsement lead over Mitt Romney heading into the primaries and emerged victorious; four years later, Romney held a convincing advantage in endorsements and received the nomination.

Public attention also matters: a one percent increase in a candidate's share of public attention is expected to lead to about a one-sixth percent increase in their APV. Among Democrats, past public attention winners include John Kerry (35.42 percent) and Barack Obama (43.83 percent), both of whom won the party's nomination. Republican public attention, however, has not always been predictive. John McCain won the 2008 nomination despite finishing fourth in public attention; Mitt Romney won the 2012 nomination while placing second.

Interestingly, while endorsements and public attention help us understand the APV, poll standing heading into Iowa does not. Some eventual primary winners, such as John Kerry, John McCain, and Barack Obama, lagged at least one of their competitors in national polls before any votes were cast. This finding shows that the results in early states may not reflect the opinion of the whole country.

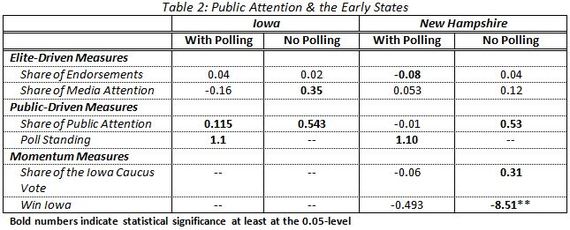

So far, the evidence demonstrates the importance of both elites and the public in presidential primaries, but what about Iowa and/or New Hampshire? Table 2 indicates that elite endorsements do not help candidates increase their vote shares in either early state. In fact, more endorsements lead to a lower percentage of the vote in New Hampshire. In 2016, both Bernie Sanders and Donald Trump won New Hampshire while receiving few, if any, elite endorsements. Prior to this year, other endorsement frontrunners include Howard Dean, Hillary Clinton, and John McCain, none of whom won in Iowa.

Public attention, on the other hand, helps candidates get more votes in the early states. If we look at the No Polling columns, a candidate can increase his/her share of the vote by one percent for every two percent increase in public attention. Candidates such as Barack Obama (2008) and Donald Trump (2016) rode waves of public attention to win New Hampshire. John Kerry did likewise in 2004 after his come-from-behind Iowa caucus victory over Howard Dean.

Implications

What does all of this mean? First, public attention is important in understanding who wins presidential primaries and should be considered when pundits and political scientists make their predictions. Second, when it comes to political elites, getting endorsements does not actually help a candidate win either Iowa or New Hampshire. While political elites can still play an important role in who wins a primary, there are a few recent examples where underdogs have won Iowa and New Hampshire. Finally, public attention at least helps us understand Trumpmania a little bit better.