Shown here are veterans working with Achilles International, which trains disabled vets to compete in marathons. (Courtesy of Achilles International)

Jake Schick was hurled from his vehicle after hitting an IED in Iraq in 2004.

Never losing consciousness, the Marine waited 42 minutes for help. He suffered multiple broken bones and burns, had 46 operations, and lost his right leg below the knee. Despite that, he considers himself lucky – after overcoming post-traumatic stress disorder.

Schick now runs an organization that tries to help other veterans do the same.

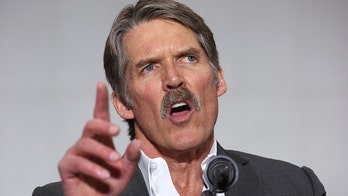

“If you have broken bones and severed ligaments, you can have a prosthetic leg like I’ve got. But you can’t have a prosthetic brain,” said Schick, executive director of 22Kill, whose name represents the 22 veterans who on average commit suicide every day.

Schick’s organization was among the 40 veterans groups Donald Trump announced he had donated to last month, following a January fundraiser. The media focus at the time was on whether the Republican presidential candidate’s claims squared up with reality; group’s like Schick’s were peppered with fact-checking phone calls to see whether the money really was making its way to them.

Somewhat lost in the firestorm over the $5.6 million in donations, however, was the work that some of these groups – particularly the lesser-known ones – do, ranging from providing therapy dogs to arranging outdoor adventures for American heroes.

Schick, whose group got $200,000 from the fundraiser, admitted disappointment that few in the media wanted know about 22Kill’s mission and were interested only in Trump.

But as the dust settles on the fundraising controversy, that work continues, beyond the media spotlight. For 22Kill, that means bringing attention to the suicide rate among U.S. service men and women, and trying to bring that number down – through therapy, fishing, outdoor activities, or whatever it takes.

“I know first-hand. I’ve lost a lot of my guys,” he said. “I’ve known more warriors to die from suicide than in combat. They die not from physical injuries but injuries you can’t see.”

CLICK HERE FOR MORE ‘PROUD AMERICAN’ STORIES

Several other groups on the donation list are focused on making recovery from PTSD and other injuries part of their mission.

Among them is America’s VetDogs, an organization that provides dogs to veterans to help with PTSD, hearing, seeing and seizure response.

“Having a dog brings a sense of companionship and an ability to count on something,” Andrew Rubenstein, director of marketing for America’s VetDogs, told FoxNews.com. “Some veterans are out in public for the first time in years. It gives them confidence that it’s going to be okay and gets veterans back into society.”

Rubenstein said it costs about $50,000 to breed, raise, train and place each dog for a veteran. The group serves 60 veterans per year, he said.

Another unconventional way for vets to deal with unseen injuries is what Racing for Heroes calls “motor sports therapy.” The organization brings together vets with PTSD to team up and build race cars. More than 200 veterans have participated, at a cost of $8,500 per person, though the veterans pay nothing.

“Based on the testimony of the heroes, we’ve saved lives,” founder Nick Evock said, adding the program is “giving these heroes a task and a purpose.”

Other veterans are engaged in a more conventional type of race – marathons.

“The goal is to train for a 26.2 mile marathon, but the byproduct is the comradery and team, from this family of veterans,” Janet Patton, director of the Freedom Team for Achilles International, told FoxNews.com. “People served in units together, or were at Walter Reed together, and are now together again.”

Freedom Team is one part of the broader Achilles International organizations that trains disabled people to compete in marathons. The veterans team was established in 2004, and more than 1,000 disabled veterans have competed in marathons held in Detroit, New York, Palm Beach, Chicago, L.A., Boston, San Diego and other locations.

These aren’t separate marathons. The veterans are competing – some with prosthetics, others in wheelchairs – with the other runners.

Another group on the list was American Hero Adventures, which plans hunting and fishing outings for veterans, adventures that have taken them from Africa to Mexico to New Zealand to locations all over the U.S.

“The focus is on heroes, military, law enforcement, EMS and federal law enforcement agencies,” said retired Army Capt. Troy Givens, the organization’s president and founder, who was injured after an explosion in 2010 in Afghanistan. He retired from service in 2014.

The largest recipient of the Trump fundraiser money, with $1.1 million, was the Marine Corps Law Enforcement Foundation, which provides scholarships to the children of fallen U.S. Marines and federal law enforcement officials. The group also offers aid to injured Marines and law enforcement agents, like paying for medical costs not covered by health insurance.