Legacy of colonial education system

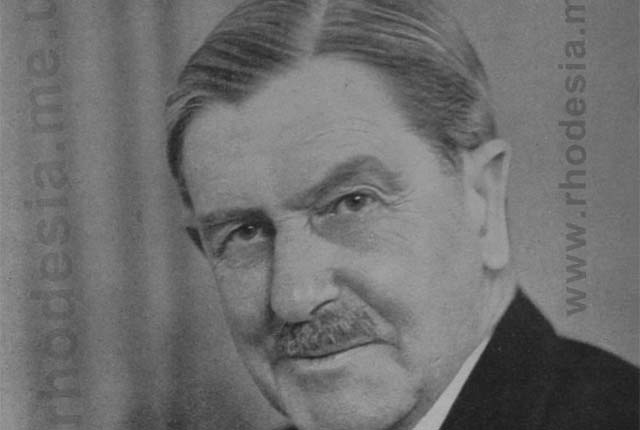

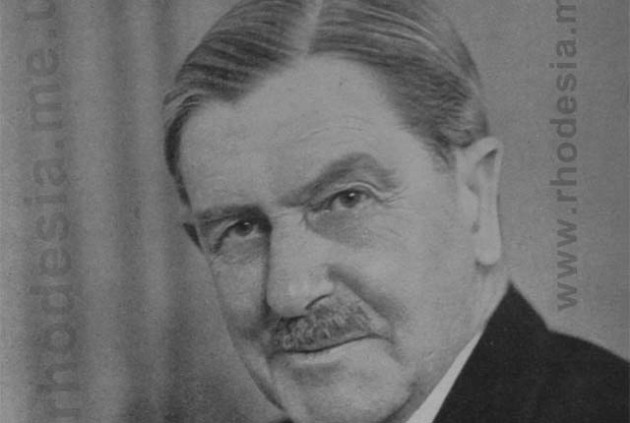

In 1920, Rhodesian Prime Minister Godfrey Huggins (pictured above) placed more emphasis on the superiority of the European child in Rhodesia. Legislators called for a system of education for white children, giving little attention to Africans

Dr Sekai Nzenza On Wednesday

Several acts were then passed with the main purpose of limiting the education of Africans. At that time, the European settlers also believed that contact with Africans was to be carefully controlled, especially in education.

“WHY didn’t your mum learn to speak English? Could she even read or write?” wrote my cousin Reuben’s son on a WhatsApp message from Australia.

Reuben did not respond to his son at once.

Instead, he showed us the message and expressed anger and disappointment with his son.

“You see, these Diaspora children have no respect. They judge their own grandparents’ level of education based on ability to speak English. This boy refers to his grandmother as ‘your mum’. She is his grandmother, for goodness’ sake,” Reuben said.

These kind of outbursts from Reuben are becoming normal ever since he made the decision to come back home from Australia, leaving his wife and children there. Reuben is making small progress in farming and mining. But he misses his family. They miss him too, especially, his 12-year-old boy Kuziva.

“Kuziva is the more sensitive and caring one of my three children. He really identifies with Zimbabwe and with being African,” said Reuben, settling himself comfortably in the sofa at my house, beer in one hand and his iPhone in the other.

“Then teach him what he needs to know,” said my cousin Piri. “You could start by telling Kuziva that I was the brightest student at St Columbus School, but I failed to get money for high school education. I could have been a nurse. If the world was fair, I would be working in London and making a lot of money right now. But look at me. I have a Grade Seven Certificate, no course, no skill. My English is not good. I am uneducated,” said Piri, her face genuinely sad.

“Who says you are uneducated? Who defines education? Is education only about writing and reading English?” asked Reuben. Then two of them started arguing, as they often do. My brother Sidney, being the teacher that he is, then intervened. I could relate to most of his historical explanations because I grew up under the same colonial education system.

Back in the village, before independence, most children at our school did not graduate past Grade Five. Only 10 of us went as far as Grade Seven. Then two, including myself, went to high school. The rest stayed home and got married, if they were girls. The boys went to look for work at the European owned farms. After a short time working as casual farm workers, picking and grading tobacco, they returned home and tilled the land. Many people, apart from my grandmother, knew education was important. But it was hard to find money for school fees.

My mother brewed beer, sold pottery and groundnuts to raise money for our school fees. She was not the only one who struggled to educate her children. In colonial Rhodesia, many parents struggled to find money for education.

During those days of struggle, we did not know that there was a colonial system or a policy, to stop us Africans from getting an education.

In 1920, the Rhodesian Prime Minister Godfrey Huggins placed more emphasis on the superiority of the European child in Rhodesia. Legislators called for a system of education for white children only. Little attention was given to the Africans.

In 1929, the Report of the Education Commission summarised the problem of a European boy if he was not educated: He is: “Unambitious, unable to seize opportunities, dull, without polish, lacking in initiative, inefficient, undisciplined, unstable, purposeless, superficial, and further from the fulfilment of Rhodes’ ideals than the youth of any other part of the British empire. Finally, he is smug and has no wish to improve.”

Then The Rhodesia Herald, in one opinion piece, argued that the European youths should not be blamed too much. The problem was to do with lack of opportunities for them. The paper then blamed the newly educated Africans for taking employment from the white men.

Several acts were then passed with the main purpose of limiting the education of Africans. At that time, the European settlers also believed that contact with Africans was to be carefully controlled, especially in education. In one report titled, “Rhodesia — Enlightened administration of African welfare, an 80-year progress report,” the government argued that it was too expensive to educate the African child beyond secondary education: “The aim is therefore to make secondary schooling available to some 50 percent of those who complete the primary course.”

George Stark, (there is a school in Harare named after him) the then Director of Native Education in colonial Rhodesia from 1934 to 1954 introduced a policy of “practical training and tribal conditioning”. Its main purpose was to develop a big pool of cheap unskilled African manual labour. Another one of its goals was to keep Africans to the newly formed Tribal Trust Lands.

Our village is situated in what was called a Tribal Trust Land. This is where we still live today.

By careful selection, the top 12,5 percent of those completing primary school were to be creamed off for a full six academic course of secondary education which led on to qualifications for entrance to University. It was at the higher educational levels that the African and European educational systems merged. Members of all races attended the various modern technical colleges and the University in Salisbury together. As a result, a minority of black students mixed with the majority of white students at the University of Rhodesia. But the journey to get to that university was a long one. Very few Africans made it.

Africans who did not make it past Rhodesia Junior Certificate or RJC, enrolled in apprenticeship such as domestic science, woodwork or building.

In general, Africans were being educated “to make better lives within their own community, staying in rural areas and away from white development, and avoiding competition with white clerks, labourers or storekeepers.”

Some students who failed to access University level education in Rhodesia left the country and attended Fort Hare University in South Africa. Others went to Europe, America, Canada and Australia as refugees, returning home at independence.

When Zimbabwe went to the general elections in 1980, there were many adults who could not read or write, let alone sign their names. They used a thumb sign to vote.

Today, there are still a number of adults, most of them elderly, who cannot read or write due to the legacy of racial discrimination in education. Sometimes, when a text message arrives in the villages, grandmothers take the phone to a nearby school to ask for help to read and respond to their children and grandchildren living afar.

“Such history of our past, must be told, so that the children understand that their grandparents suffered from lack of education opportunities,” said Reuben.

Dr Sekai Nzenza is a writer and cultural critic.

Comments