Why Everyone’s Suddenly Talking About Gut Bacteria

Research suggests the microbiome plays a role in determining everything from weight to behavior, but there’s much we still don’t know.

The Internet is full of bizarre, frankly gross corners. Take, for example, the popular YouTube channel devoted to popping giant whiteheads, blackheads and cysts. These videos – which star pus in all its various consistencies– are hard to stomach, but they make for easy viewing compared to another, growing category: do-it-yourself fecal transplants.

In one such video, a man cheerfully whirrs a banana dipped in chocolate (his homemade feces stand-in) in a blender. In another, a woman films herself preparing a fecal transplant enema made with her own poop. And then there is the story of Josiah Zayner, as told by the Verge, who sequestered himself in a hotel room to ingest homemade pills of his friends’ excrement.

The through line here is poop’s perceived ability to transfer beneficial qualities from one individual to another. If you’re able to choke down a healthy person’s stool, this line of thinking goes, you can harness their gut bacteria to achieve cures for everything from irritable bowel syndrome to weight gain. “Until fecal pills are widely available, a blender and an enema bag may be the next best thing,” declares a 2014 Vice article.

Like much of the questionable health advice on the Internet, this category sprouted from actual research, although in many cases, the facts have been dangerously distorted. While clinician-supervised fecal transplants have proved curative for specific gut conditions such as colitis, there’s no clinical evidence that drinking a friend’s feces from a blender confers any health benefits. Meanwhile, the process can be extremely hazardous. Ingesting untested feces, unsurprisingly, leaves the body vulnerable to a host of parasites and diseases, including hepatitis, E.coli, salmonella, and rotavirus.

That this genre exists at all, however, belies a mainstream fascination with a topic once considered both boring and taboo: Gut bacteria. Over the last decade, scientific interest in our gut bacteria — and, by extension, our feces, which are roughly 40% microbe — has exploded. We’re still only scratching the microbial surface, but there’s evidence the bacteria populations that exist within us play an important role in both our physical and psychological well–being.

Related: Danone’s big bet on tiny bacteria

This coincides and contributes to a sea change in the way we think about metabolism and weight loss. In a blockbuster study recently published in Obesity, researchers tracked former contestants of the reality TV show The Biggest Loser for six years; directly after appearing on the show, all 14 of the study’s participants weighed significantly less than they had before it started. Unfortunately, they also burned far fewer calories than would be typical for someone at their new size, a shift that persisted years after the initial weight loss. By the study’s close, all but one of the participants had gained back much, or all, of the weight they’d lost.

Season 8 winner Danny Cahill is on the left. Photograph by NBC/NBCU Photo Bank—via Getty Images

While the results were disheartening — heartbreaking, even — they help explain why so many of us struggle to keep weight off. They’re also a rebuttal to the maxim that weight loss is simply about calories consumed versus calories burned. Under this new lens, it’s harder to reduce obesity to a failure of willpower. Its roots are more complex, dictated not just by diet and activity level but also by metabolism, hormones, and, yes — gut bacteria.

The Activia effect.

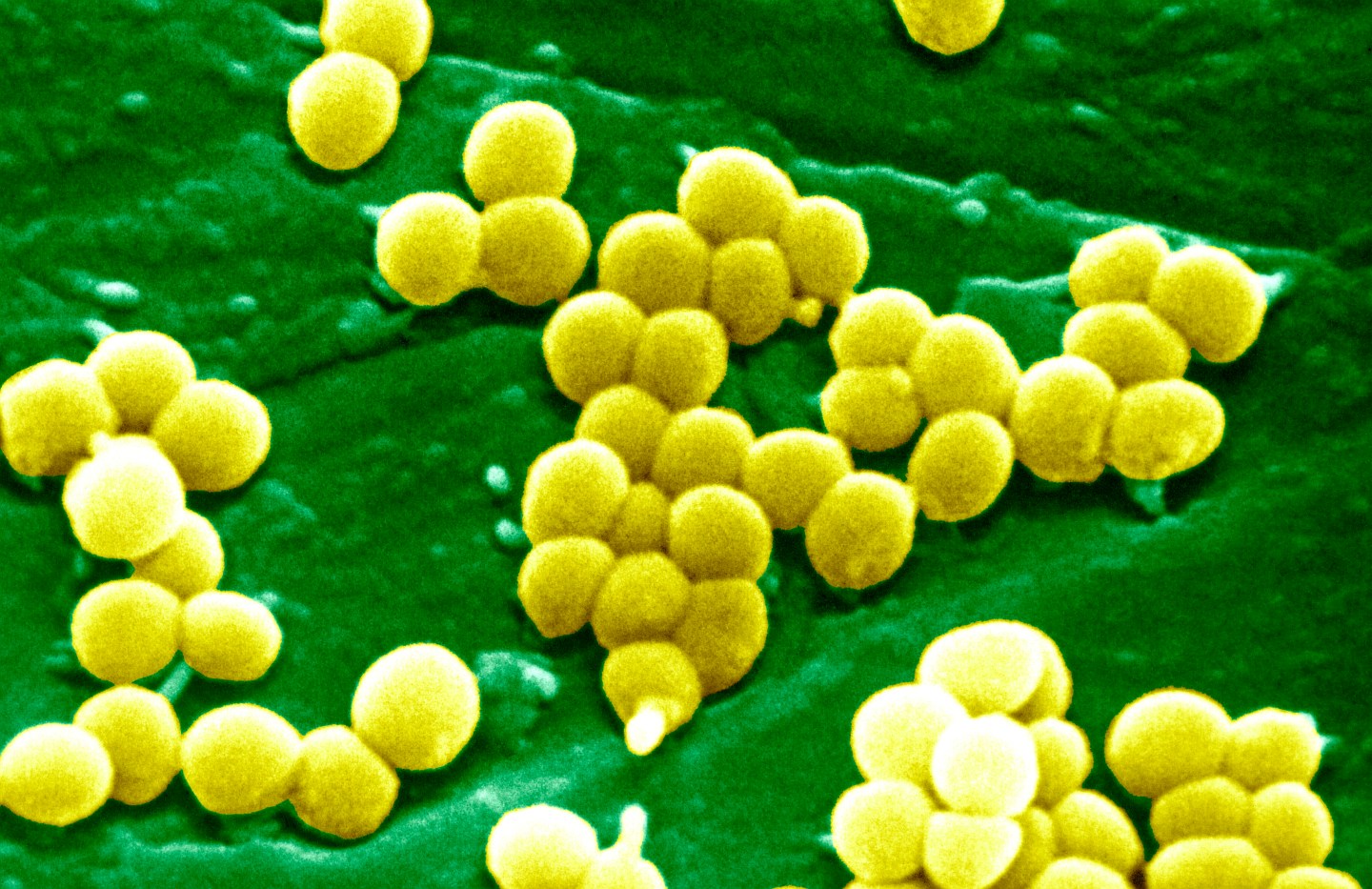

For decades, scientists’ ability to study the microbiome was limited because the vast majority of bacterial strains aren’t easily cultivated in a lab. Bacteria was regarded mostly with suspicion, an understandable position: transmitted through stool, it’s responsible for the spread of diseases such as Typhoid fever, E.coli infection and hepatitis A.

Spurred by the advent of third-generation DNA sequencing technology in the mid-1990s, which enabled the quick, cheap identification of microbe strains via their genetic code, there’s been a renaissance in bacteria-focused research. We now understand that while some bacteria is indeed pathogenic and dangerous, the vast majority of the 100 trillion microbes that reside within us are either harmless, beneficial or necessary for living a healthy life.

[fortune-brightcove videoid=4248027215001]

Part of Dr. Lita Proctor’s job is to talk to the public about bacteria. When she started six years ago as program director for the Human Microbiome Project, a federal initiative to identify and characterize the microbial makeup of human guts, “most people thought of microbes as germs and pathogens,” she says. Now, when she walks into a room people are more interested in the positive impact “good” microbes can have on their health. For this, she thanks Jamie Lee Curtis. Remember those Activia commercials where the actress applauds the yogurt for keeping her “regular?” The campaign’s claims may have been spoofed by SNL and flagged by the Federal Trade Commission, but Proctor isn’t mad. Curtis did “so much work for the field,” she says. “She helped educate people that not all bugs are bad,” as well as publicize the idea that bacteria and metabolism are connected. Activa’s ability to shape that equation may have been inflated, but the underlying idea wasn’t wrong.

Kristen Wiig as Jamie Lee Curtis during the “Activia Commercial Shoot” skit on SNL NBC NBC via Getty Images

Is bacteria making you fat?

“Every study we’ve done has shown that fat people have a different set of microbes than thin people,” says Tim Spector, a genetic epidemiologist and the author of The Diet Myth: Why the Secret to Health and Weight Loss Is Already in Your Gut. In general individuals at a healthy weight have a more robust, diverse microbe population.

Researchers are just beginning to untangle the specific ways lean guts differ from obese ones, but there’s evidence certain strains play a decisive role. Spector led a study that compared the microbial composition of identical twins in pairs where one twin was obese and the other lean. In addition to having a more diverse microbiome than their obese counterparts (microbiome meaning our bacterial ecosystem), slim twins had significantly higher populations of the strain Christensenellaceae. When the bacteria species was transplanted into mice, the mice gained less weight than mice who did not receive the transplant — an indication that skinniness can be classified as “an infectious disease” of sorts, says Spector. If true, it stands to reason that obesity can be contracted, too. Indeed, in a separate study mice who received a gut bacteria transplant from an obese participants gained weight while those who received bacteria from lean participants did not. And then there’s the documented case of a woman who received a fecal transplant from her obese daughter to treat a colon infection caused by the bacteria C. difficile. The infection went away, but the woman gained 34 pounds in a matter of months.

Taken together, these studies indicate the microbiome and metabolism are connected. So how can you keep your gut bacteria healthy — and, perhaps, keep those extra pounds at bay in the process? “We know our food plays a major role,” says Proctor, particularly food that’s rich in fiber. This is worrying news for a nation that largely subsists on a diet packed with processed, low-fiber foods. In truth, we may all contain microbiomes that are sparse shadows of our ancestors’ diverse, abundantly populated guts. Studies have shown that microbe composition is heritable in mice; if this holds true for humans, much of the population may be born at a bacterial disadvantage thanks to generational shifts in eating patterns. In cases of extreme obesity, the microbiome may be “so messed up” that diet alone may be insufficient in restoring a healthy bacteria balance, says Spector.

Related: Probiotics Are a ‘Waste of Money,’ Study Finds

And new research suggests that an off-kilter gut’s impact reverberates beyond weight. Animal studies have shown that by manipulating the microbiome, researchers also altered immune, metabolic and behavioral states, says Thomas Sharpton, an assistant professor of microbiology and statistics in the Oregon State University Colleges of Science and Agricultural Sciences.

“Now we just have to wrap our heads around how it’s able to do this.”

That isn’t an easy task. Researchers have several broad, working hypothesis validated by clinical studies, but they’re just beginning to parse out the complex relationship between bacteria and human health. “We have thousands of species that may be working alone or working together,” says Spector. Determining when and how to manipulate these strains for our benefit without unwittingly causing adverse effects gets complicated fast.

Even for more fleshed-out area of study, such as bacteria’s connection to metabolism, “we only have a crude understanding,” he says. Individual cases, such as the women who put on 34 pounds after a fecal transplant from her daughter, make for powerful anecdotes, but there’s no evidence the effect was causal; for example, it’s possible — likely, even — that other factors contributed to or completely prompted the weight gain. Meanwhile, most studies are at the animal stage — humans, as Spector puts it, “aren’t very good laboratory animals” — and so the theoretical implications on own health are valuable, but tenuous.

More research will lead to more answers: a randomized, clinical trial, in which 20 obese participants ingest capsules containing stool from healthy donors, begins this year. The results will go a long way towards determining whether fecal transplants are a viable tool for weight loss. But even if the trial produces positive results, it’s unlikely the secret to everyone’s dieting struggle is a poop pill. As a species, we’re too genetically diverse for a one-size-fits-all solution; what’s more, genetic factors may play a role in determining which strains of bacteria are able to thrive in our guts. “There is no magic bullet,” says Spector.

“We have to let the science take its course. It’s careful, painstaking work,” agrees Proctor. She knows that’s not what we want to hear, but is “begging the public for patience.”

In other words, please refrain from making yourself a feces smoothie until further notice.

‘Antibiotics have a lot to answer for.’

One of the things we do know for sure: antibiotics kill microbes.

In itself, this isn’t worrying so much as life saving. Certain bacterial species are pathogenic. Strep throat, meningitis, and sinus infections for example, can be caused by streptococcus, neisseria meningitidis, and streptococcus pneumoniae strains, respectively, and a dose of antibiotics is able to wipe out what would otherwise become a serious bacterial infection.

But we’re overusing them. Physicians routinely prescribe antibiotics when patients present symptoms for the common cold and other viral infections, succumbing to the pressure to do something. It’s estimated that four out of five Americans take a dose of antibiotics annually; not only does this contribute to antibiotic-resistant bacteria, or superbugs, but it ravages the microbiome.

“Antibiotics have a lot to answer for,” says Spector including, he suspects, the rising average body mass index in many first-world countries. (Forty percent of U.S. women and 35% of men were obese in 2014, according to the Centers of Disease Control and Prevention). In a 2015 study of nearly 164,000 children, participants who took repeated doses of antibiotics early in life weighed more at age 15 than those who didn’t. And a recent study in mice found that when the animals were exposed to antibiotics in their first month of a life — a window that likely translates to up to three years in humans — the subsequent weight gain was intensified.

Related: One in Five Adults Worldwide Will be Obese by 2025, Study Says

While the research connecting shifts in the microbiome to obesity is mounting, the condition is multifaceted. A perturbed microbiome and weight gain may be correlated, but without more rigorous longitudinal studies, we can’t draw a causal relationship between the two, cautions Proctor.

Still, avoiding antibiotics unless prescribed by a doctor and not pushing for a prescription if the infection is diagnosed as viral isn’t a bad place to start. Sadly, it’s not that easy to avoid the medication altogether.

Your steak is on drugs.

Most of the antibiotics in the U.S. go to animals, not humans. The breakdown isn’t close — last year, it was around 80% percent versus 20%. In 2014, antibiotics sold for use in livestock totaled around 32 million pounds, according to a report from the FDA.

These drugs serve a dual purpose; the first, obvious one is to protect animals from disease, which can spread rapidly in the close quarters of commercial farms. The second is less intuitive: Since the 1950s, farmers have been feeding livestock low doses of antibiotics to “fatten them up,” says Proctor.

Cattle eating feed on a farm.Photograph by Alvis Upitis—Getty Images

This has a ripple effect. Animals poop. A lot. Because only a percentage of the antimicrobial agents are digested by the livestock, the rest is excreted and mixes with the soil — traces of antibiotics have been detected in commercial vegetable crops, which means even vegetarians have likely ingest low-grade doses of antibiotics via their diet. Which begs the question: how does this exposure affect our health?

The short answer is: we’re not sure. But theories are emerging. In a 2013 paper, researchers draw a possible link between the use of antibiotics on livestock and the obesity rate, which have both “sharply increased in the U.S. over the same 20-year period.”

“While this hypothesis cannot discount the impact of diet and other factors associated with obesity,” the authors continue, “we believe studies are warranted to consider this possible driver of the epidemic.”

Antimicrobial substances aren’t just in our food. Triclosan, a microbial agent that can be ingested via the skin, is found in products such as toothpaste, deodorants and cosmetics. In a recent study on zebrafish, Sharpton found that exposure to the chemical altered the fish’s microbiome; given the results, he’s hoping to study the chemical’s impact on humans in the near future. Hundreds of substances that we think of as harmless, from emulsifiers to artificial sweeteners to pesticides, “have never been tested on microbes,” says Spector. In short, there are a lot of unanswered questions.

‘Everyone will have their microbes measured.’

This uncertainty can be frustrating — we now know the microbiome plays an important role in regulating many aspects of our health, but it can be hard to get much in the way of concrete advice. Health science is an evolving field, and scientists are loathe to make any declarative statements. Much of the available advice is supported by anecdotal evidence, rather than clinical trials.

Dr. Vincent Pedre is an internist in New York City; he says he cured himself of crippling digestive problems by reducing his intake of dairy, gluten and genetically modified foods. For a healthier gut, “I think it’s always a good idea to reduce your gluten consumption,” he says.

The message is seductive in its clarity, but prod further, and the advice becomes murkier. I don’t know of any hard evidence that shows avoiding gluten is good for microbes,” says Spector. “I know there are a lot of people around who believe everyone should be a gluten–free diet, but there are 10 times more people on these diets than have gluten intolerance.” Similarly oft-made pronouncements, such as Pedre’s distrust of GMO food or the effectiveness of the booming probiotics industry, also lack a clear, scientific consensus.

Related: How Danone gets the right bacteria in your yogurt

Adding to the confusion is the fact that because each person’s microbiome is unique, we don’t respond to foods in the same way. In a study published last year, researchers from the Weizmann Institute of Science monitored 800 participants directly after they consumed various foods to see how their blood glucose reacted (lowered levels are correlated with weight loss). For some individuals, blood glucose spiked after eating junk food, such as ice cream and chocolate. For others, oddly, the uptick was caused by conventionally healthy foods, including tomatoes, bananas and brown rice. Nearly every participant had “surprising examples,” according to lead author Eran Segal.

The study suggests a possible problem with modern-day dieting, which is typically based on rigid nutritional rules (tomatoes = good, ice cream = bad). While helpful on a general basis, on an individual level these tenets may be counterproductive. The study’s authors hope to create personalized diet profiles for participants based on stool samples. A group of startups, including uBiome and The American Gut, already offer the service. “In the future, everyone will have their microbes measured,” predicts Spector.

Proctor also envisions a near-reality in which overly broad generalizations based on questionable data — in the recent past, the majority of clinical trials used white men, results that don’t always translate neatly to the general population — are replaced with individual plans. “We should treat each person as his or her own patient.”

The future, in other words, is high-tech and promising. For now, though, Proctor’s advice is perhaps disappointingly retro. To maintain a healthy gut, she advises, eat more fruits and vegetables. Try fermented foods and foods naturally high in fiber, while cutting back on processed ones. Get enough sleep. Exercise. Don’t take antibiotics unless prescribed by a doctor.

Because while there’s still much we don’t know, it’s safe to assume a healthy gut is connected to healthy habits.