Returning to Earth in a three-person Soyuz TMA spacecraft is a white-knuckle rollercoaster ride.

It begins with a four-minute "de-orbit burn", continues with a scorching 1,600C dive through the atmosphere, and ends with a "soft" landing described by one astronaut as being like a "head-on collision between a truck and a small car".

The ISS crew will have had the best training, but no simulation on Earth can entirely prepare anyone for the experience of re-entry and descent.

While the US space shuttle would glide home gracefully on delta wings, the Soyuz tumbles to Earth using the same tried and trusted system the Russians have employed since the 1960s.

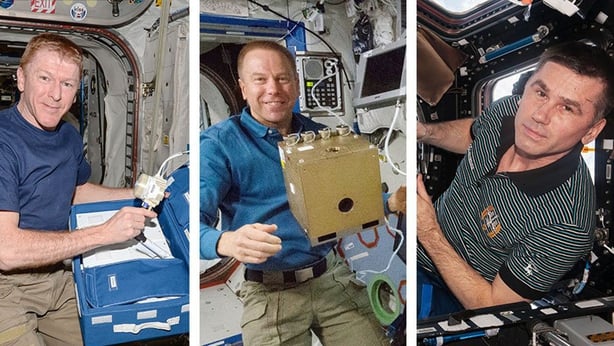

First, Major Tim Peake, Tim Kopra and Yuri Malenchenko will transfer to the Soyuz, which has been attached to the International Space Station (ISS) since it carried them into orbit six months ago.

Closing the Soyuz hatch marks the official end of the Principia mission, less than four hours before the trio are due to be back on Earth.

Only the middle part of the three-section spacecraft, the descent module, completes the journey home.

It alone is designed to cope with the friction-generated heat as the capsule ploughs through thickening atmosphere at more than 800km/h.

The other two sections, the service module containing propellant and control systems and the orbital module that housed the crew during their launch, plunge into the atmosphere and burn up.

Automated computer systems should steer the astronauts on the correct trajectory, but if necessary Soyuz commander Malenchenko can make minor adjustments using a hand controller to fire eight thrusters.

Unique view shows #Soyuz spacecraft departing the station with moon in the background. https://t.co/g3EpFqzaEk

— Intl. Space Station (@Space_Station) June 18, 2016

Getting the main engine de-orbit burn right to start the process of re-entry is absolutely crucial. It must last exactly four minutes and 45 seconds.

If the rocket fires for too short a time, the spacecraft could skip across the top of the atmosphere, like a stone skimming a lake, and shoot off into space. If the burn is too long, the Soyuz will come in at too steep an angle too fast, and risk being incinerated.

Some three hours after undocking, and 19km from the space station, explosive bolts break the Soyuz into its three component parts.

Describing the moment in a European Space Agency (ESA) video, Italian astronaut Paolo Nespoli said: "It felt as if there was somebody outside with a sledgehammer."

As the descent module flies through the atmosphere it becomes enveloped in a ball of glowing plasma - hot, electrically charged particles of gas - which lights up and then blackens the windows.

NASA astronaut Doug Wheelock described the Soyuz descent as "kind of like going over Niagara Falls in a barrel but the barrel is on fire".

Gravity comes as a shock to the crew after spending six months in free-floating weightless conditions.

.@Space_Station crew members are successfully on their way home. Watch landing at 4am ET: https://t.co/ws7AQi38ah pic.twitter.com/LOiQtnQE2O

— NASA (@NASA) June 18, 2016

The rapid deceleration causes them to be pushed back into their shock-absorbing seats with a force of more than five gee - five times normal Earth gravity.

Helen Sharman, who became the first Briton to go into space in 1991 when she spent eight days on the Russian Mir space station, said: "The ride back to Earth is really exhilarating, I think far more exciting than the launch. On the launch you get three and a half gee maximum ... but returning to Earth it's five and a half gee.

"Compared to feeling weightless, the astronauts feel incredibly heavy, really pushed back into the seats. Even just lifting up your arm to push a button on the control panel, your arm weighs probably ten or more kilos so it's quite an effort."

Mr Nespoli said it was easy for people living on Earth to forget how strong a hold gravity has on their bodies and the objects around them.

It is time to go home for British astronaut, Tim Peake, after a busy few months at the International Space Stationhttps://t.co/f6Dc6O4vLL

— RTÉ News (@rtenews) June 18, 2016

He recalled: "You look at stuff and you feel your hands are heavy, you feel your watch weighs a tonne, your books, the materials around you, your head is extremely heavy, and its really, really, really a very strong feeling."

That degree of discomfort assumes that the capsule makes a gradual, aerodynamic re-entry, as planned. If something goes wrong it may be necessary to choose the "ballistic re-entry" option. This involves a more rapid descent that generates up to nine crushing gees, squeezing the astronauts' lungs and making it hard to breathe.

Unlike early NASA spacecraft that were dropped into the ocean, the Soyuz thumps down in the remote heart of the Kazakhstan steppe.

Friction on the spacecraft's heat shield reduces its speed from 28,000km/h to 827km/h during the transition from space to atmosphere.

Fifteen minutes before the landing, four parachutes deploy and dramatically slow the vehicle's rate of descent.

Two pilot parachutes unfold first, followed by a drogue that brings the speed down to 286km/h.

Finally, the main parachute, with a surface area of 10,764 square feet, emerges.

To dissipate heat, it is designed to "swing" the capsule at an angle of 30 degrees before shifting it back to a vertical position.

The main chute reduces the descent speed to 24 feet per second, which is still much too fast for a comfortable landing.

So just one second before touch down, two clusters of three retro-rockets beneath the module fire and the spacecraft hits the ground at 3m/hr.

"Soft landing" is a misnomer, according to Nespoli.

"You prepare for it by putting your arms against your body not touching any of the metallic parts .. you're not talking, not to put the tongue in the middle of your teeth, and you're laying there trying to be as inside your seat as well as you can.

"You're waiting for this soft landing to happen which for me felt like a head on collision between a truck and a small car - and of course, I was in the small car. When this happened it was like, bara-boom! Everything shook .. then silence .."