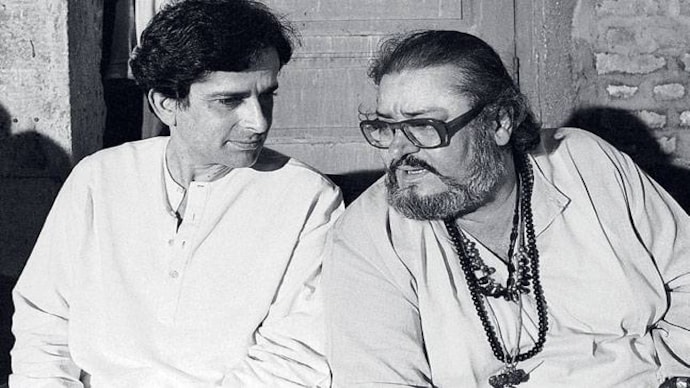

The Kapoor brothers

A mellow look at two legendary siblings from Bollywood's first family.

It's hard, if not impossible, to grow and flourish under a banyan tree. The Kapoor brothers, Shashi and Shammi, had two gigantic figures looming over them. Father Prithviraj Kapoor had dominated the theatre scene for decades before his two boys grew up, having shone in silent cinema equally, before starring in India's first talkie, Alam Ara. Then there was sibling Raj Kapoor-older than Shammi by seven years and Shashi by 14-who had perched himself at the top, with his much-loved star persona of the tramp, and as a solid boss of RK Studio.

Not surprisingly, Shammi, when he started out, was written off by audiences and the film industry alike as a boring, goody two shoes "Raj Kapoor clone", with 18 box-office flops in a row.

Much as the Bombay film industry is reviled for being nepotistic, it is actually replete with stories of famous star-sons and star-siblings failing to make it. The Kapoor brothers are notable exceptions simply because each of them grew sideways as smaller plants from under the banyan, coming out of the shadows to find their place under the sun.

As far as family trees go, Shammi's stylised urban hero was more a natural extension of Dev Anand's. It is not a coincidence that his breakthrough hits- Tumsa Nahin Dekha and Junglee- were movies Dev had first turned down.

The movie projection of Shammi as a mirror image of his off-screen persona-goofy, funny, full of restless energy and an unabashed Casanova-was something his new wife Geeta Bali helped him draw out, both in the choice of films and roles. Was Shammi merely an actor? No. Rauf Ahmed's biography calls him Bollywood's 'Game Changer' and through this painstakingly detailed biography, you can adequately sense why.

The term Bollywood, with its connotations of the romantic musical genre, owes its origins to Shammi from the swinging '60s. As do some of the typically 'Bollywood' films-starring Amitabh Bachchan (in the '70s), Aamir/Salman/Shah Rukh Khan (in the '90s) to Ranbir Kapoor (post-millennial)-thereafter.

What did Shammi get so right? The script, as he admits, was roughly the same-boy likes girl, who doesn't respond to him first but eventually gives in, which is when the villain steps in. It was really about the music. Shammi collaborated closely with his friend Jai (of the composer duo Shankar-Jaikishen); and Mohammed Rafi, his playback voice. And man, he knew his music. Most don't know, for instance, that Shammi had composed the lilting Amitabh song Neela aasman so gaya from Silsila (1981) a decade before.

That's not all. Shammi took a personal interest in song visuals and choreographed his own tracks. He saw dance as an uninhibited physical expression of music rather than a series of well-planned steps. There is a wonderful episode in the book of the cast and crew of Junglee trooping from Bombay to Pahalgam (in Kashmir) and Kufri (near Shimla) looking for 12 inches of snow to shoot a song. When they reached the final location, no one knew what Shammi was going to do. Neither did Shammi. The next morning he slid down the snow-peak screaming "Yahoo", a moment frozen in movie history.

Shashi, in contrast, seems to be the understated sibling. If being third in a line of hugely popular brothers wasn't hard enough, he was also the less aggressive, genteel half of 'Shashitabh'-the 'angry young man' Amitabh Bachchan's foil in the '70s (in Trishul, Deewar, Kaala Patthar, Shaan?).

Shashi (inarguably the handsomest Kapoor) was a major star in his own right. But more significantly, he pursued an alternative career in relatively minimalist movies aimed at both international and locally more discerning audiences.

Aseem Chhabra's account neatly divides Shashi's career into three phases. His Merchant Ivory and other international productions, which even picked up top gongs, at Berlin (Heat and Dust) or Venice (Siddhartha). As the overworked mainstream superstar in cookie-cutter mode, often doing "really bad movies", he would show up at multiple shoots the same day, remembering neither his own lines nor the film's inconsequential storylines, a trait that prompted Raj Kapoor to label him "taxi". But, the book also looks closely at Shashi's work as filmmaker, where he persistently strived to break free from the mainstream clutter, producing Junoon, Kalyug, 36 Chowringhee Lane, Vijeta-gems, all of them.

Shammi, we learn from Rauf's biography, was a hunter (literally and figuratively), an inveterate traveller and an impulsive man, prone to occasional bouts of arrogance. Shashi used to call him "Santa Claus", in an obvious reference to his generosity as brother. Shashi, we gauge from Chhabra's monograph, was very much a Santa figure too-a benevolent businessman or producer, who'd throw open 5-star hotel rooms, passing on his hard-earned money to pamper his 'art-house' cast and crew, making losses all through.

Both come across as very Punjabi, 'dildar', larger-than-life figures, which is a big part of their charm, making you want to meet and know them better. Sometimes (and this is a lament as a Mumbai journalist), before you know it, people turn into books. Sadly, Shammi is no more, and Shashi is not keeping well.

If journalism is its first draft, then history, you can tell through these two accounts, is going to remember them very fondly, alongside their towering brother Raj Kapoor, for their distinctly unique contribution to films.

Chhabra's severely slim volume, in that sense, is a marvellously produced/packaged/edited tribute. But Rauf's is a better book. For one, because it is almost wholly in the voice of the subject. The author spends hours talking to Shammi-"first in the family after Papaji (Prithviraj) to pass matric and enter college"-reminiscing about his glory days.

Shammi is devastatingly candid about his emotional highs and lows, relationships and breakups. The book goes deeper to examine his rollickingly promiscuous rock-star life. Many of these anecdotes, at least ones relating to film shoots and professional collaborations, could hugely enliven Annu Kapoor's radio pravachans on Bollywood.

In fact, there is even a germ of a script in there that can only be titled 'Rockstar'. That was ironically the movie where we saw grand old man Shammi on screen for the last time.