The answer to such a question may seem obvious but it is not. While the interrogation is meant to be provocative, the intent here is not to be controversial, but to raise a serious point, as Middle Easterners in general and Arabs in particular ponder their future and how to best preserve and protect their interests.

Simply stated, and this would be an educated conclusion, non-Arabs today interpret and opine about Arabs far more than indigenous thinkers. It is depressing to read book after book, article after article, opinion piece after opinion piece on the Arab world written by individuals whose attachments to local societies are mostly alien. Even those who demonstrate empathy tend to be highly critical and while there is plenty of room to be very severe with many concerns, one simply cannot brush aside the perspectives of nearly 500 million individuals. Arabs may be submissive to authoritarian rule, but their interests and objectives are genuine even if, for socio-cultural reasons, most are voiceless.

Of course, opposite assumptions, including a vociferous Arab loathing of sympathetic non-Arabs who devote their energies to bridging gaps between East and West and who often earn scorn in their own societies for allegedly “going native”, are equally troubling. Often, those in positions of some authority attempt to place roadblocks on the publication of monographs or essays, or who even deny foreign scholars attendance at conferences, perceive non-Arabs as intruders. These self-appointed judges of scholarship — an unnatural phenomenon if there ever was one — tend to do more harm than generally believed, though few can bring themselves to acknowledge the phenomenon, content to move along under the circumstances as if no harm was done.

Naturally, both of these assertions ought not dismiss the significant contributions made by many Arab and numerous Western academics (both from Arab and non-Arab origins) who devote time and energy to study, understand, explain and cherish, yes cherish, Arab civilisation.

To be sure, the list is long, and one can cite important work by Albert Hourani, whose seminal book A History of the Arab Peoples is still one the most authoritative studies available today. Others have made valuable contributions too, ranging from Edward Said to Hisham Sharabi and including Saad Eddin Ebrahim, Constantin Zureiq, Halim Barakat and many other prominent scholars who toiled and continue to elucidate. Some of these men and women migrated to the West, especially the United States, to teach at Harvard, Columbia, Georgetown and several other universities and, over time, published valuable studies on a slew of topics from history to politics to architecture and medicine. A few leading poets such as Said ‘Aql, Nizar Qabbani, and Mahmoud Darwish have left their marks too. Contemporary Arab literary figures have also added value, including Gibran Khalil Gibran, Taha Hussain, May Ziade, Nawal Al Saadawi and Fatima Mernissi. For years, leading authors in the Arab Middle East, offered exquisite works, like those of Naguib Mahfouz who earned a Nobel Prize in Literature in 1988 or Abdul Rahman Munif, whose sharp exposes on socio-political developments on the Arabian Peninsula stand as a genuine contribution to our understandings of the many transformations under way here.

Such efforts, and there are many more than it is possible to list in this essay, highlight valuable contributions. Still, it would be an error to assume that Arab writers, composing their work primarily in Arabic have any impact on decision-makers in their homelands or outside. Likewise, one can venture to declare that American academics from the Arab world have even less of an impact, even though their lingua franca is English and many are quite prolific. Regular attendees at the annual conventions of the Middle East Studies Association or the American Historical Association or any number of similar professional societies can attest to widespread participation, the availability of useful resources, and the proclivity to dig into what ought to be pertinent topics. Policy relevance, however, is another matter.

In the post-9/11 era, the number of books published on the Middle East, terrorism, violence, Al Qaida, Osama Bin Laden, the Taliban, Daesh (the self-proclaimed Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant), and assorted sensational topics that are crucial to perceived western security interests have overtaken genuine scholarly tomes. Sadly, the vast majority of this genre of books is authored by non-Arabs, many of whom shroud themselves in the authority cloak but who, in reality, harbour sharp dislikes, if not outright hatred of Arabs.

Those who fall in the more honest category must therefore devote significant amounts of time just to keep up with these legendary experts, most of whom fall under the Kool-Aid variety (just add water), on account of their ignorance or peripheral knowledge of the Arab and Muslim worlds. With rare exceptions, western journalists fall into this category as well, available to be easily manipulated to satisfy corporate interests. In fact, most of this fare highlights preferences for the sensational that no longer need any evidence: One simply accuses, judges and executes with the mightiest sword ever — the word. It behoves everyone, however, to be more careful for our lives are on the line.

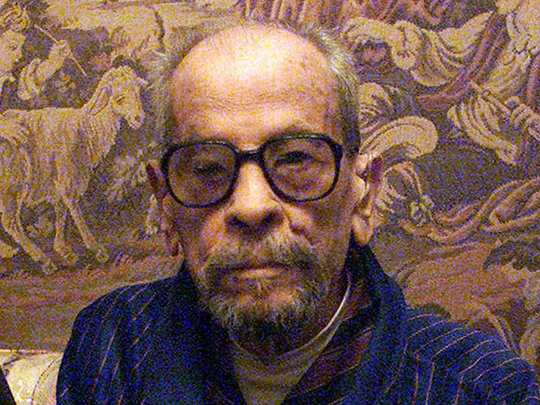

Dr Joseph A. Kechichian is the author of the just published From Alliance to Union: Challenges Facing Gulf Cooperation Council States in the Twenty-First Century (Sussex: 2016).