- India

- International

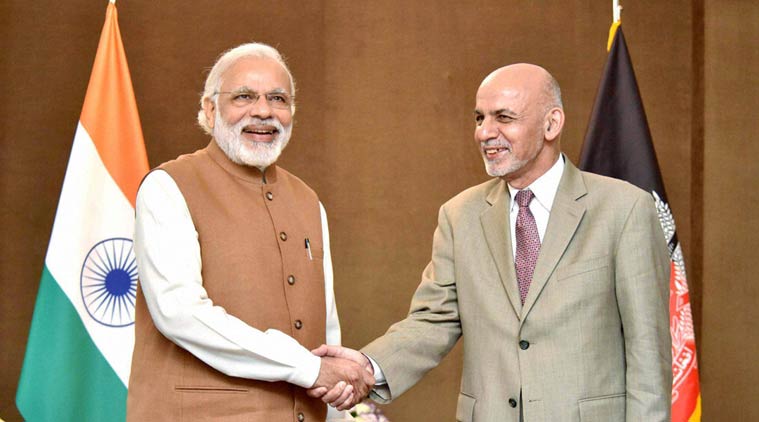

In Afghanistan, PM Narendra Modi’s weekend stop in Herat, a massive crisis of state

This weekend, when Prime Minister Narendra Modi inaugurates the Salma Dam, the largest of the development projects India initiated after the new Afghan republic was born, the unprecedented street celebrations in Herat will hide a grim reality.

PM Narendra Modi is scheduled to visit Herat on Saturday to inaugurate the Salma Dam. At over $275 million, the most expensive of India’s infrastructure projects in the region. (Source: PTI)

PM Narendra Modi is scheduled to visit Herat on Saturday to inaugurate the Salma Dam. At over $275 million, the most expensive of India’s infrastructure projects in the region. (Source: PTI)

The Taliban stopped the night bus from Kabul to Kunduz Tuesday night, and began to check IDs of the men to see who worked for the government. Then, the bus pulled into a side street. “It was like a horrific scene out of a terrible dream,” said Ay Noor Uzbik, on her way home from a women’s empowerment conference in Kabul. “I kept thinking, this is it, this is the last moment of my life.”

For at least 10 people, it was. As it is for many ordinary Afghans every day.

This weekend, when Prime Minister Narendra Modi inaugurates the Salma Dam, the largest of the development projects India initiated after the new Afghan republic was born, the unprecedented street celebrations in Herat will hide a grim reality.

Few of Afghanistan’s international supporters are even asking about the next steps on its development trajectory — focusing instead on the war material needed to keep the state from lurching over the abyss. For ordinary Afghans, Salma will likely to be the last transformational development project for years, perhaps decades.

[related-post]

Haibatullah Akhundzada, the new Taliban chief, signalled with the Kunduz massacre that his policies would be no different from those of his predecessor Akhtar Mansour, slain in a US drone strike last month. Installed with the backing of Pakistan’s ISI, Akhundzada is committed to battering the Afghan state into submission. India, and Afghanistan’s other international allies, have to find a way to defeat this campaign — or see a jihadist-run wasteland emerge at the heart of Asia. But guns alone won’t be enough.

Death by cash

Cash, it is clear, isn’t the magic weapon. In a paper published by the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute earlier this year, Richard Ghiasy, Jiayi Zhou and Henrik Hallgren noted that more money has been spent in Afghanistan since 9/11, in real dollar terms and corrected for inflation, than was received by all of Europe through the Marshall Plan after World War II. Yet, Afghanistan remains one of the world’s least developed countries. There are precious few projects like the Salma Dam, which will create income-generating infrastructure: the Kajaki Dam in Kandahar, due to come online this year, is one expensive exception, along with some roads and bridges.

The reasons are corruption, inefficiency, massively wasteful aid programmes that funneled more money back to donor nations than to Afghanistan. To be fair, however, Europe’s war-ravaged states had a robust history of industrial society and its institutions, while the very warp-and-weft of Afghan life had been incinerated by decades of war.

Deeper reasons for the crisis go to the heart of Afghanistan’s tragic political history.

From 1953, Afghanistan’s modernising Prime Minister, Muhammad Daud Khan, nationalised key sectors of the economy, and introduced central planning. But Daud’s economy was deeply tied to foreign aid, with Afghanistan leveraging competition between the US and USSR to draw in assistance. Foreign sources provided some three quarters of the capital for Afghanistan’s five year plans — and by 1973, nearly two-thirds of its revenue.

The Afghan state never developed a sustainable internal resource base. Big chunks of the foreign funding were frittered away — moreover, because of bureaucratic incompetence and corruption.

In 1979, Soviet troops crossed the Amu Darya river, sparking off the war that would shape the country’s modern history. The war saw Afghanistan’s rural economy bombed almost to the point of annihilation — and the collapse of the state was followed by the emergence of a highly criminalised economy, in which trafficking and narcotics by warlords played a key role.

From 1998, the Taliban regime brought a semblance of order — but it had no agenda for rebuilding the state. Its primary source of income remained opium trafficking from Helmand and Kandahar. Illegal cross-border trading and smuggling of goods into Pakistan and the post-Soviet Central Asian states is estimated at over $ 2 billion a year.

In 2001 began a crippling drought that would run for 7 years, killing off a fledgling revival of the agrarian economy. In 2002-03, the year after international forces went in, the country received some $ 404 million in military and civilian aid. That figure had ballooned to a staggering $ 15.7 billion by 2010-11.

This aid economy, and the ensuing boom in everything from salaries to property values, left Afghanistan the renter economy it was in the 1950s — just bigger and even more vulnerable.

Now that the West has scaled down its presence and the aid economy has vanished, skilled Afghans are leaving the country in droves, there are growing numbers of jobless youths in the cities, and the countryside can no longer count on even the crumbs.

Political meltdown

Fixing this crisis of state-building while also fighting a war needs a government with extraordinary determination and grassroots legitimacy. But the National Unity Government created to resolve the electoral deadlock caused by the bitterly-disputed 2014 election is on the edge. The agreement that allowed President Ashraf Ghani to take power with Abdullah Abdullah as his Chief Executive — a position that does not exist in the Constitution — is scheduled to expire in September. No one knows for sure what might follow.

Under the 2014 agreement, a Loya Jirga, or General Assembly, was to be called to amend the Constitution to accommodate the position of an executive Prime Minister — thus legitimising the position Abdullah now holds. To call a Loya Jirga, though, the government first needs to hold Parliamentary and District Council elections. The terms of both bodies expired in 2015.

Former President Hamid Karzai is among those calling for a traditional Loya Jirga, or council of tribal elders, to chose an alternative government — an option the government has flatly rejected.

Karzai’s former aide, Umar Daudzai, has meanwhile, sought to mount pressure on the government by casting himself as a peacemaker with the Taliban. Since a meeting early this year — at which the Taliban insisted on the right to choose its interlocutors — Daudzai has exchanged at least five drafts on a potential political agreement. The Taliban’s Doha office has agreed to negotiate with an interim government — which would presumably replace the one in office — and allow some foreign troops to remain in the country, say sources close to the process.

Fresh elections, opposition politicians argue, might be another option, while some in President Ghani’s circles suggest he could ease out his Chief Executive — no easy option, since Abdullah won close to 50% of the vote in the first round of the Presidential election.

These won’t, however, offer a solution to the seemingly intractable crisis of state. Leading an army through a long war against insurgents backed by a hostile neighbour will need real political leadership — and mass legitimacy that can come only from building a sustainable economy generating employment and incomes.

Can Afghanistan do it? For now, the military and the people have shown a dogged resolve to keep driving down the dangerous, rutted path they hope will lead to a better future. But the road to peace is pitted with minefields and booby-traps.

More Explained

EXPRESS OPINION

Apr 26: Latest News

- 01

- 02

- 03

- 04

- 05