The window of the stuffy room must not have been opened for a couple of years. Eugene Dokukin sits at his computer and speaks at a breathtaking pace about the achievements of his group of hackers. They steal information from the Russian Ministry of Internal Affairs and from the servers of the so called Donetsk People’s Republic that is pro-Russian. Through hijacked CCTV cameras, they spy on the activity of rebel fighters and the Russian forces in Eastern Ukraine and the Crimea. They hack into the social media accounts of separatists and block their payments transactions. These nationalistic cyberattacks are organised in a derelict Soviet apartment block in Kiev, the capital of Ukraine.

Hackers that break into data systems usually avoid publicity and use pseudonyms, even when communicating with their peers. The Ukrainian Dokukin has chosen another path. For two years, he has led the group Ukrainian Cyber Forces that administers cyberattacks against the Eastern Ukrainian separatists and Russia. In his view, he and his troupes are waging a justified cyberwar against an invader.

In spite of the threats, Dokukin does not admit he is afraid for his life.

The opponents, pro-Russia hackers in Eastern Ukraine and Russia, are also active on the cyber front. Data protection researchers have gathered plenty of proof of cyber operations executed by hackers supported by Russia in the last two years. Russia occupied the Crimea in the spring of 2014 and also got involved in the Eastern Ukraine armed conflict.

Dokukin says that when he started the cyber activism, he knew he would be targeted by the pro-Russia crowd but still decided to take the risk.

“They are trying to attack me 24/7. They are constantly trying to steal my passwords. My personal information and address and those of other activists are published online. Trolls slander us. They put psychological pressure on us. Watch out for us. We are coming to kill you. I have received hundreds of messages like these.”

In spite of the threats, Dokukin does not admit he is afraid for his life.

Most of the time in the group is spent sabotaging the communications and payments transactions of the rebels supported by Russia. In practice, the goal is to prevent the use of as many websites, social media accounts and bank accounts as possible. According to Dokukin, most of the activity of the group is legal and does not require hacking into data systems.

The group collects information about the connection of separatists to military operations or simply just proof of the fact that they have violated the terms and conditions of PayPal or Twitter, for example, which ban threatening, harassment and misinforming the service provider, among other things. Complaints to service providers have in several cases led to closing social media or payment service accounts.

”From 2014 to February this year, we blocked more than 300 accounts in various payment systems and banks. This means preventing transactions worth 12 million dollars, at least,” Dokukin calculates.

It is difficult to prove the figures correct or false but in any case, Dokukin’s group seems to make a lot of effort to close accounts, in particular.

However, complaints to social media and payment services are not even nearly always successful. Apparently, PayPal is especially reluctant to take the complaints of the Ukrainian group into consideration. But according to Dokukin, one Russian company providing payment transaction services has closed several accounts.

It is no surprise that the opponent uses the same means. Dokukin defends the Ukrainian government, whereas a hacker group that calls itself CyberBerkut opposes it and supports Russian actions in Eastern Ukraine.

So, one of the weapons of cyberwar is quite mundane and does not require much knowledge of information technology. But of course, Dokukin’s group certainly resorts to stronger means, as well. If they don’t get a website closed by complaining to the administrator, they break into data systems.

“We Hand the Information over to Security Services”

On the Eastern Ukrainian front, there are daily battles in spite of the truce agreed on in the Minsk Treaty. In Kiev, there are no blazing guns but cyberattacks are fierce.

”We wage war with the means of war. We break into a website and make it crash. Sometimes, we will put in a banner saying Stop Russian Aggression,” Dokukin says and shows us examples of websites his group caused to crash.

The group also hacks into social media accounts to collect information. The communication of targets, or “terrorists” as Dokukin calls them, may be followed for a long period of time.

The group also hacks into social media accounts to collect information.

”We acquire the information we want without the user knowing and we hand it out to SBU, the Security Service of Ukraine.”

According to Dokukin, he has not received funding from the Ukrainian government for his operations although he estimates the information given by him has led to several arrests.

Ukrainian Cyber Forces invest a lot of time in hacking into CCTV cameras in Eastern Ukraine, the Crimea and Russia and monitoring the manoeuvres of soldiers and military equipment in Eastern Ukraine and the Crimea.

Russia has not admitted to having any troupes in Ukraine even though a lot of evidence of its presence has been published. Dokukin searches for a video clip on his computer where three men in military uniforms are buying perfume in Luhanski in the midst of war in 2014.

”The material is from a camera in the separatist area of Eastern Ukraine. You can clearly tell by the appearance, accent and military beret of the men that they are Russian. Maybe they are buying perfume for their girlfriends or maybe they need it themselves. Terrorists need perfume too,” he laughs.

Dokukin also points out that in the video, certain soldiers in poor Eastern Ukrainian regions seem to visit gold shops day after day and spend a lot of money. He claims that this is proof of the funding the separatists receive.

”I Impose Daily Sanctions against Russia”

Hacking into social media accounts is not a very demanding job. Also, it does not take long for someone who knows what they are doing to hijack streams of CCTV cameras. However, Dokukin’s group has also succeeded in more demanding break ins into data systems.

He is particularly proud of stealing information from the governments of Russia and the Eastern Ukrainian separatists.

“We exposed hundreds of gigabytes of data on the hacked servers of the Russian Ministry of Internal Affairs. We also hacked into the servers of the Donetsk People’s Republic and stole plenty of confidential information from the separatists”, he says.

Dokukin produces a document that, according to him, is proof of large payments to the members of the parliament of the Donetsk People’s Republic. He also presents a long list of personal data of separatists with photos and addresses.

We also hacked into the servers of the Donetsk People’s Republic and stole plenty of confidential information from the separatists”

The hacktivist believes that every cyberattack, no matter how small, is throwing a spanner in the works for the rebels supported by Russia.

“Setting up a service again and again costs money. The United States and EU only impose economic sanctions once a year but I impose sanctions every day.”

I have to ask him again whether he really is not scared for his life after all that he has done and all the death threats he has received.

“If they wanted to kill me, they would have already done it two years ago. It is not like killing opposition in Russia. Putin can easily send a killer and nobody will investigate it. It is harder to do it in Ukraine. There is a danger but nothing has happened to me in two years so I don’t worry. "

Undeniably, Dokukin’s group does all it can to disrupt the operations of separatists and Russia. However, he does admit that the opponents, Russian cyberspies, have resources that are superior by far.

For example, he has no doubt that the opponent’s hacktivists receive direct support from Russia and that Russia executed the cyberattack that caused a part of the Ukrainian electric grid to crash.

“Nobody else has resources like that,” he argues.

Listening to Dokukin, it has to be pointed out that, in spite of all his expertise, he is also someone involved in the conflict. He is a politically motivated activist hacker, a hacktivist. Due of this, we have to turn to someone else to assess the activities of the opponent: data protection experts researching the attacks.

Far Superior Hacktivists on the Opponent’s Side

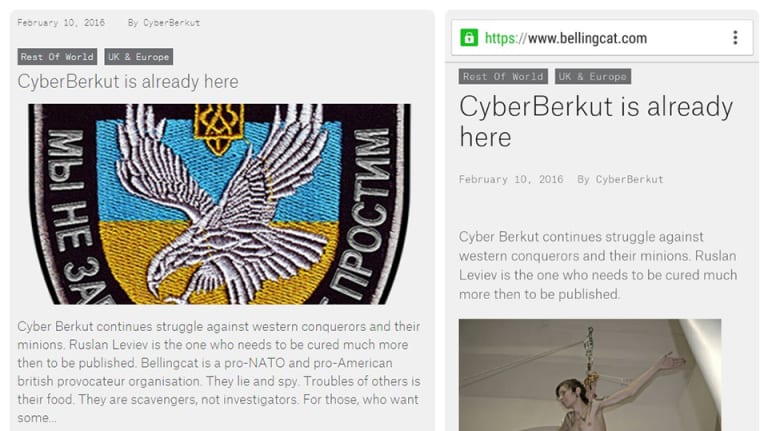

It goes without saying that there are hacktivists on the opponent’s side, as well. One of the most significant groups is called CyberBerkut. It is against the current Ukrainian government and supports the annexation of the rebel areas of Eastern Ukraine to Russia. To them, people like Dokukin are enemies. On its website and in its messages, the group says it is also fighting against “Western occupiers” and NATO. In its propaganda, the group firmly states that the current government oppresses the people in Eastern Ukraine, and shows videos of civilians being attacked by the Ukrainian army.

The name of the group is derived from the former special police force of Ukraine, Berkut. The unit is remembered for its heavy-handed approach when reigning in protests on the Maidan Square and for shooting protesters in February 2014.

The pro-Russian hackers of CyberBerkut boast about their attacks and proclaim their propaganda on social media accounts they have acquired, for example. Ruslan Leviev is a founder of Conflict Intelligence Team, and a Russian citizen journalist co-operating with the the group Bellingcat investigating the Ukraine conflict. When he published an article about a Russian soldier wounded in Ukraine that Sergey Shoygu, the Russian Minister of Defence, had visited, CyberBerkut started to put pressure on him. The hacker group broke in to Leviev’s computer and stole his personal information.

“They stole my passport information, my phone number and my home address and published them. After that, I have received constant death threats like We know where you live, We will be there tomorrow, and Prepare to die,” Leviev says. He has also published other evidence about the presence of Russian troupes in Ukraine

“They also stole photos of me with my female friends and published them claiming I met up with underage girls and raped them. The youngest one of my friends is 21,” Leviev explains and says everyone close to him will be in danger.

The group also hacked into the website of the group Bellingcat and left a threatening propaganda message slandering Leviev as well as Bellingcat. Bellingcat is a group of voluntary citizen investigative journalists from around the world known for its investigation into the incident of the Dutch aeroplane shot down in Ukraine in July 2014, in particular. (Kuvakaappaus Bellingcatin viestistä; hirtetyn näköinen mies ja Cyber Berkutin uhkaava teksti.

However, the most impressive attack by CyberBerkut so far is probably hacking into the system used for counting the votes in the Ukrainian presidential election in 2014. Data protection researches have tracked down every detail of how the attack was executed and recently published new information about it in the publication of the NATO Cooperative Cyber Defence Centre of Excellence, Cyberwar in Perspective: Russian Aggression against Ukraine.

On the day of the election, the software that was supposed to show real-time information about the counting of votes, did not work for 20 hours. 12 minutes before the polling stations were going to close, the attackers uploaded a photo of the false winner, the right-wing leader of Ukraine, on the website of the central election committee. The photo was immediately broadcasted on Russian TV channels. The report by the NATO Cooperative Cyber Defence Centre of Excellence concludes that the activists of CyberBerkut did not execute the attack on the election systems by themselves but they used or were supported by the know-how and tools of the cyberspies of a nation-state.

**Yle has also received comments **from other data protection sources stating that the group worked in close cooperation with the most skilful cyberspies of Russia. This strongly implies that it is not merely a group of voluntary hackers but a part of a larger network of state-led cyberespionage and hybrid warfare.

On the whole, the reports of security software companies like Symantec, Kaspersky, F-Secure and Trend Micro suggest the conclusion that Russia or pro-Russia groups dominate Ukrainian networks.

Data protection researchers have found some of the most sophisticated malware in the world, such as Black Energy, Turla/Uroburos, Dukes and Sofacy/APT28/Sednit, on the computers of the Ukrainian government, businesses, army and citizens.

The software is so progressive that developing them requires the resources of a software company. This kind of malware is not available on the market and is also not used by regular cyber criminals trying to steal money. Consequently, recognising this kind of software on the computers of the army, government or a company is a strong implication of the target being a victim of cyberespionage.

Yle interviewed data protection researchers in the Japanese company Trend Micro that have examined attack campaigns by cyberspies active in Ukraine. In addition to this, Yle acquired information from several other experts in the industry, some of which preferred to stay anonymous.

State-led Cyberespionage for a Decade

The one cyberespionage campaign in Ukraine that has most likely been the most active one is the Pawn Storm. The campaign or the group of attackers is also known as Sofacy, APT28, and Sednit, named after the malware the cyberspies used. Unlike CyberBerkut, the group does not present the results of its attacks publicly. Data protection specialists consider the group to be a part of the State Intelligence Service of Russia

Cyberspies have attacked the computers of the Ukrainian government, military forces, businesses and politicians. Outside of Ukraine, they have targeted NATO, the United States and several European countries. In Russia, the group has spied on opponents of the Putin government, activists and media.

In recent years, attacks have also been detected elsewhere. When the Arab countries criticised the Russian strikes to Syria last year, cyberspies attacked the countries critical of Russia and the computers of Syrian opposition politicians in exile. Last year, the group attacked the German Parliament, and this spring, they targeted the Turkish media.

The most recent finding was made in April. Cyperspies targeted the Germany’s Christian Democrats, the political party of Chancellor Angela Merkel.

In May, the Federal Intelligence Service of Germany spoke to the press agency Reuters and confirmed that Sofacy/Pawn Storm hit the German Parliament a year ago. The Intelligence Service blamed the attack on Russia.

Russian nonconformists have also been actively spied on this spring, according to Feike Hacquebord, a Senior Threat Researcher specialised in the attack campaign. He does not allow his photo to be published but describes his latest analyses in an interview with Yle.

“It is clear that Pawn Storm selects targets that can be seen as a threat to the policies and interests of Russia. The people behind it have extensive resources and launch frequent attacks,” he says.

Historical Cyberattack Cut Power

After long-continuing cyberespionage, Russia seems to be expanding its cyber operations further than just espionage, namely strikes that can cause physical damage and inconvenience to civilians, as well. The first assault was launched late in 2015.

On the Eve of Christmas Eve, employees managing the electric grid in Ivano-Frankivsk, Eastern Ukraine, got a big surprise. They could no longer manage the functions of the electric grid on their computers. They could see on their screens that an outsider was moving the cursor and switching electricity off in an expert manner. The software called the Ghost Mouse is just one of the tools in the arsenal of the attackers.

Preparations for the strike had been started months before, at least, by phishing for passwords. After that, the attackers were able to break into the systems that control the electric grid.

The attackers were exceptionally skilful. Not only were they able to execute a multi-phased break-in into the data systems but they also knew how to operate the electric grid. The electricity supply of 225,000 people cannot be cut off by the click of a single button, but they knew exactly what to do.

Citizens getting frustrated because of the power cut tried to report the fault but calls did not get through. The Distributed Denial of Service was executed by the hackers by artificially creating a queue in the phone service which prevented the network company from seeing the extent of the problem. It took several hours before the employees of the energy company were able to bring the power back on.

However, data systems were still not working because the KillDisk software that overwrites hard drives had destroyed the software. The first cyberattack in the world targeted at civilians had been a success.

The strike was in the global news in January. Experts started to frantically find out who administered the strikes and why. During the spring, Yle interviewed several experts investigating the strike in order to shed some light on the background of the strike.

“The Whole Code of the Malware Is Made in Russia”

Data protection experts from the United States who studied the attack conclude that the level of sophistication and motive of the assault imply that there is a well-organised executor with plenty of resources behind it. In addition, researchers know exactly what kinds of techniques and malware the attackers used.

In the attack of the power station, a major role was played by the malware BlackEnergy3 and its component KillDisk that destroys hard drives. They are also essential tools for certain Russian cyberspies, in particular.

The whole code of Black Energy that has been developed for years is of Russian origin

”We can never be a hundred per cent certain but based on the behaviour of the attackers, the BlackEnergy3 software that was used, and the target, we can conclude that in this case, the attackers were Russian. In fact, the whole code of Black Energy that has been developed for years is of Russian origin,” says Kyle Wilhoit, a Senior Researcher in the company Trend Micro.

For several years, Wilhoit has studied cyberattacks targeted at the control systems of industrial businesses, in particular. He assumes that the same malware has been used to attack the railways and a mining company in Ukraine, as well. In addition, CERT-UA, the Computer Emergency Response Team of Ukraine, has reported that the same malware has been found on the computers of Kiev airport.

In these cases, the hacks have only gone as far as reconnaissance. The attackers have not managed to or not wanted to cause physical damage. A power cut lasting hours is quite a poor result for an extremely expensive cyberattack joining the forces of several top experts.

However, Wilhoit considers the break-ins to be extremely serious. He states that it may have served as preparation for an attack on critical targets.

”The attackers could have had the critical infrastructure of the country under their control. They could have paralysed the railways, prevented the operations of the mining company and halted all operations at the airport,” he says.

“A Power Cut Lasting Hours - Poor Result for an Expensive Cyberattack, Why Did Russia Do It?“

The attackers were not necessarily even trying to cause as much physical damage as they could. It is possible that the expensive and demanding assault was simply military research and development. In the same way as Russia has tested its new weapons in Syria, it has now completed a test launch of its cyber weapon in Ukraine.

Hacker Eugene Dokukin doing his tricks on the Ukrainian side also thinks that strikes like these will not be seen again anytime soon.

“I do think there will be attacks but not such complicated ones. There will rather be regular DDoSing, hacking and Russian propaganda, information warfare, in particular. It is easier and cheaper than cyberwar. The two types of warfare are combined.”

It hardly comes as a surprise because it has long been assumed that Russia and the United States have the capability to launch such assaults. Fears have been expressed about disaster scenarios concerning water and electricity supply.

The deterrent has, however, not been as powerful as intended since the two countries have not used all their abilities and not been able to present cyber weapons in the Victory Day parade on the Red Square.

Now that Western researchers have found that the attack was conducted skilfully, Russia has shown what it can do in terms of cyberwar when it wants. Watch out for us.

Edit 14:17: Ruslan Leviev is not a member of Bellincat, but has been in co-operation with the group.

Translated by: Katja Juutistenaho