Learning to stop the cultural habit of lying

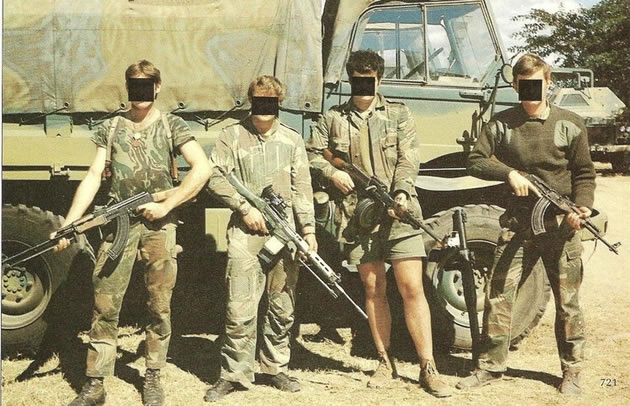

After a whole night at a pungwe with the comrades, everyone lied to the soldiers when asked whether they had seen the terrorists, as the Rhodesian soldiers called the liberation fighters

Dr Sekai Nzenza On Wednesday

When we were growing up in the village, long before independence, we lied a lot. My grandmother, Mbuya VaMandirowesa, my mother, the neighbours and some relatives told us to lie because it was the “normal” way to protect ourselves in some situations.

At school, Headmaster Muchando held his punishment stick in hand and always asked us why we were late coming to school. Instead of saying we had to plough the fields because Mbuya said school was not important, we lied. We said, “Sorry Sir, we woke up too late.” Headmaster Muchando knew we were lying, but he did not beat us for that. Instead, he told as to wake up earlier. Then he hit us on the cuffs of our legs three or four times. We promised that we would never be late again. But we were lying. It was not possible not to be late for school, especially during the rainy season when planting had to be done.

My mother always told us to lie about her whereabouts when she went to visit my father in Salisbury or if she went to her maiden village. “Where is your mother?” people asked when they passed by the homestead. We said, “she has gone to collect clay for moulding pots. She has gone to collect a debt behind the mountains. She has gone to visit Mbuya Mashonganyika across the Save River.”

My mother was never too far in our lies. Yet she would be gone for days. The reason for the lies was to stop neighbours such as Nyakudirwa the village chicken thief from breaking into our chicken coop or goat pen if there was no adult around our homestead.

Mbuya gave us strict instructions to say takaguta or we have eaten, if anyone that she did not approve of asked us to share a meal with them. She said we could easily get bewitched by people who were jealous of our family or those who wanted to settle old conflicts with Mbuya or Sekuru.

At one point my sister Charity, (the one who later became Zimbabwe’s diplomat in New York and other places) and I were coming back from an Anglican baptism and ceremony many kilometres away from our village. An elderly lady saw us and asked whose children we were. When she discovered that we were Mbuya Va Mandirowesa’s grandchildren, she said “Come into my house and eat some food”.

We were hungry and thirsty. Just above the fireplace inside her hut were juicy roasted pieces of mhembwe, or buck. She offered that to us with leftover cold sadza. Charity, being the older one, quickly said, “Taguta”, (we are full). That was a lie. We were starving. The old lady begged us to eat, but we said all we wanted was water because our stomachs were full of food.

The old lady knew we were lying. She shook her head with sadness and said, “Next time I see your grandmother, I shall tell her to teach you that I am no stranger. Why would I bewitch you?” With embarrassment, we said it really was not like that at all. We were quite full. It was such a painful lie because we would have enjoyed a tasty smoked piece of the buck.

Some lies in the village had serious long-term consequences. When Mainini Nkazana got pregnant before anyone knew her boyfriend, it was the talk of the village and beyond. Most of us knew that Mainini’s secret lover was Mr Sanboy, the storekeeper at Muzorori & Sons Store. But Mr Sanboy was already married. Mainini Nkazana then lied to the boy wekwa Zenda from across the Save River. She said the pregnancy had occurred during the one brief intimate encounter she had with him. Since he was a rather quiet and polite boy, he accepted the pregnancy without question. He made plans to marry her.

Then Mainini Nkazana went into labour earlier than expected and the baby would not come out of her womb. Mbuya Gambiza and the other women gathered around Mainini Nkazana and asked her to tell the truth about the men she had slept with or the baby would never come out. That was the custom then. You could never lie about the paternity of a first child. If you did that, you could easily die in child labour. After much pain, Mainini Nkazana confessed that she had slept with Mr Sanboy on more than three occasions.

Upon that confession, the baby came out very easily and gave out a loud healthy cry. Everyone said the baby boy was a spitting image of Mr Sanboy.

“So why did you want to kill yourself and the baby by telling a lie?” the midwives asked Mainini Nkazana.

She just smiled and asked if someone could please go and tell Mr Sanboy that his son had arrived. Mainini Nkazana spoke as if her earlier lie about the child’s paternity was normal.

During the liberation war, we got used to lie to the soldiers very well. After a whole night at pungwe with the comrades, everyone lied when asked whether they had seen the terrorists, as the Rhodesian solders called the liberation fighters.

Just before writing the Grade Seven examinations, we were required to produce a birth certificate from the Native Commissioner’s office. Since no village births were recorded, parents guessed birthdays and years in which we were born.

Today, we know that the dates and years on my birth certificates and that of siblings are a lie. And we are not the only ones with official lies on our personal records. But such lies had to be told, or you would never write an examination or go to high school.

Many years later, I travelled from America where I was living, to visit my sister Charity when she was working as a diplomat in Ethiopia.

I said to her, do you ever lie when people ask you to comment on the situation in Zimbabwe? She quickly said, “Why would I lie? People need to fully understand the events of Zimbabwe within a historical and political context.”

I then said to her, well, some of us living in the Diaspora know life is hard in Zimbabwe. “And how do you know that? From the media?” she asked. I said, yes and added that people from Zimbabwe do call and say life is hard because of sanctions. I think Charity must have forgotten for a moment that I was actually her sister and she did not have to put on that serious professional diplomatic voice in briefing me about Zimbabwe.

Afterwards, I joked and reminded Charity of the number of times we used to lie back in the village, when telling little lies was almost part of our culture. Then she spoke like the big sister that she is, telling me that in professional and personal life, we must depart from the village behaviour of telling little lies because what might appear to be a little lie can cost us serious credibility and reputation. Having travelled so far away from the village, we must make the big leap to avoid lying and work towards transparency, no matter how difficult such a cultural shift might be.

But some lies in our cultural habits are hard to leave us. Take my niece Shamiso, for example. Sometimes she lies for no reason at all. When we want to go to the village and I ask her to meet us in town, near Fourth Street (now Simon Muzenda Street), she always says that she is already in a kombi and will arrive in a few minutes. Then we wait. An hour later, she arrives, and jokes that she had lied when she said she was in a kombi.

She was actually getting dressed. She argues that if she tells us the truth, then I would have gone to the village without her.

No matter how I have tried to tell Shamiso to tell the truth, this little habit of lying does not seem to leave her.

Changing a cultural habit requires discipline. But, one day soon, we must conquer this troublesome undesirable habit of telling big and small lies.

- Dr Sekai Nzenza is a writer and cultural critic.

Comments