Frankenstein: Freak events that gave birth to a masterpiece

19 May 2016

Two hundred years ago, on the lush green shores of Lake Geneva, a teenager called Mary Shelley wrote the world’s first Science Fiction story. Her revolutionary novel inspired countless writers and filmmakers, and now two new exhibitions, at either end of this vast and lovely lake, shed fresh light on her gripping tale, and the dramatic events that inspired it. WILLIAM COOK visits the source of Frankenstein.

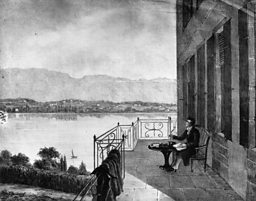

Cologny, view of Geneva from the Villa Diodati by Jean Dubois, late 19th century / Centre d’iconographie genevoise, Bibliothèque de Genève

When Mary Shelley sat down to write Frankenstein, in May 1816, in the Villa Diodati near Geneva, she never could have foreseen how her story would shape popular culture for centuries to come. She was only 18 and this was her first attempt at fiction.

Yet as these two new exhibitions reveal, that summer a collision of freak events created the perfect climate for a masterpiece. So what were the extraordinary factors which gave birth to Frankenstein?

The circumstances that brought Mary Shelley to the Villa Diodati were worthy of a novel in their own right

The circumstances that brought Mary Shelley to the Villa Diodati were worthy of a novel in their own right. She’d travelled to Switzerland with her young lover, the Romantic poet Percy Bysshe Shelley.

They’d been invited here by Mary’s stepsister, Claire Clairmont, who’d eloped here with another brilliant poet, Lord Byron – notorious for his numerous love affairs, most infamously with his half-sister (he’d been forced to flee abroad to escape this scandal, and the rabid interest of the British press).

Byron came here in the footsteps of his hero, Genevois writer Jean-Jacques Rousseau. And now the Shelleys followed Byron, kick-starting the Swiss tourist trade.

Like Byron, Percy had left a wife - and two children - back in Britain. Mary had also borne Percy two children of her own. However instead of ending up on the Georgian equivalent of the Jeremy Kyle Show, Byron and the Shelleys channelled the charged emotions of these tangled trysts into art.

(l-r): Percy Bysshe Shelley, 1819 by Amelia Curran | Mary Wollstonecraft Shelley, 1840 by Richard Rothwell | George Gordon, Lord Byron, 1813 by Richard Westall / all National Portrait Gallery, London

Mary was doubly inspired by the constant presence of these two great poets. In this quiet lakeside village, far from home, there were few distractions to dilute the creative energy she imbibed from them.

As these famous poets sat up late, putting the world to rights, Mary sat and listened.

As these famous poets sat up late, putting the world to rights, Mary sat and listened. Yet despite her reticence (or, perhaps, because of it) her creation eclipsed theirs.

Lake Geneva was another powerful source of inspiration. Shut off to travellers by Britain’s wars with France, Western Europe’s largest lake was now open to British visitors again. Surrounded by huge snow-capped peaks, it was unlike anything in Britain.

Byron pictured on the verandah, Villa Diodati, c. 1816 / Rischgitz / Getty Images

Alice Roberts at Villa Diodati

Professor Alice Roberts visits the house where Frankenstein was born

Taken from the 2014 series The Secret Life of Books.

It was on a dreary night of November that I beheld the accomplishment of my toils. With an anxiety that almost amounted to agony, I collected the instruments of life around me, that I might infuse a spark of being into the lifeless thing that lay at my feet.Narration of Victor Frankenstein, Chapter 5

When the sun shone it was idyllic, but in stormy weather it was the ideal setting for a tempestuous tale like Frankenstein.

When the sun shone it was idyllic, but in stormy weather it was the ideal setting for a tempestuous tale like Frankenstein.

If the weather had been fine, Mary might have never written Frankenstein. However that summer the weather was awful – not only in Switzerland, but all around the world.

Now we know why - a massive volcano had erupted in Java – but at the time this ‘year without summer’ was a mystery.

Crops failed and famine was rife, sparking social turmoil throughout Europe. For Byron and the Shelleys, the problem was less acute.

Stuck indoors for days on end, Byron suggested they all have a go at writing ghost stories. None of their efforts were up to much, apart from Mary’s Frankenstein.

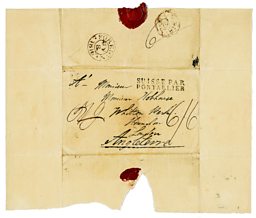

Hand-written envelope by Lord Byron to his Cambridge friend John Cam Hobhouse, 23 June 1816 / Murray Collection, National Library of Scotland

This letter was sent from Evian, the first stop on a boating tour of Lake Geneva which Byron took with Percy Shelley. The two poets visited the Château de Chillon and Clarens — the setting of Jean-Jacques Rousseau’s Nouvelle Héloïse.

A letter from Byron

I have taken a very pretty villa in a vineyard — with the Alps behind — and Mt Jura and the lake before — It is called Diodati — from the name of the proprietor — who is a descendant of the critical and illustrissimi Diodati.Lord Byron, writing to John Cam Hobhouse

> View large image in new browser window

Lord Byron's letter to Hobhouse from Evian, 23 June 1816 / Murray Collection, National Library of Scotland

If you only know Frankenstein from the movies, Mary’s novel is a revelation. It’s a compulsive page turner, but it’s also brimming with ideas. Her father, William Godwin, was a leading radical. Her mother, Mary Wollstonecraft, had been a feminist pioneer. She’d grown up surrounded by artists and intellectuals. Her writing wrestles with the great philosophical issues of the age.

The genetic engineering she foresaw has become everyday reality. Blade Runner is a direct descendant of Frankenstein

Strictly speaking, Frankenstein isn’t actually a ghost story. There’s nothing supernatural about it. Like all the best Science Fiction, it’s about the here and now. Subtitled The Modern Prometheus (after the Titan of Greek mythology who stole fire from the Gods) it grapples with ethical dilemmas which still trouble us today.

Do we have the moral right to create artificial life? Are scientists creating a brave new world we can’t control? Mary anticipated the danger of separating science from morality. In 2016, the genetic engineering she foresaw has become everyday reality. Blade Runner is a direct descendant of Frankenstein.

These two Swiss exhibitions are very different but they complement each other perfectly.

Frankenstein, Creation of Darkness, at the Fondation Martin Bodmer, belies its lurid title. It’s a serious academic study, at one of the world’s leading bibliographical museums, scrutinising Mary’s eclectic sources and the evolution of her haunting tale.

Among the highlights are handwritten pages from her first draft, with Percy’s comments in the margins. ‘You can see the very gestures of the writer,’ says the exhibition’s curator, David Spurr, Professor of English at Geneva University, as he shows me round.

Lord Byron, Le Retour at the Chateau de Chillon is equally meticulous. Here the focus is on Byron, and his visit to this medieval castle with Percy in 1816, but there’s also plenty about Mary. ‘At that time, she really had time to think for herself, and write for herself,’ says the Chateau’s Director, Marta Sofia dos Santos, as we walk around the ramparts.

Though the contents of the show are fascinating (letters, diaries, manuscripts...) the best exhibit is the location – looking out across Lake Geneva, where Byron and Percy nearly drowned, in one of the sudden, violent storms you get so often on this lake.

The Fondation Martin Bodmer is even more evocative. It’s just around the corner from the Villa Diodati, where Mary began writing Frankenstein. Today the villa is the private residence of British film director Alan Parker. A plaque outside records that Byron used to live here, but there’s no mention of Frankenstein.

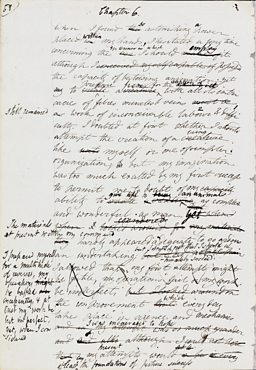

The manuscript

Alice Roberts examines the earliest surviving manuscript of Mary Shelley's Frankenstein

Alice Roberts takes a closer look at Frankenstein in 2014 series The Secret Life of Books.

> View large image in new browser window

First autograph manuscript version of Frankenstein, or, the Modern Prometheus, 1816 / Abinger Collection, Bodleian Library, Oxford

Chamonix and Mont Blanc

Vue de la Valée de Chamouny pris près d’Argentière by Carl Hackert / Centre d’iconographie genevoise, Bibliothèque de Genève

In July 1816, Percy Shelley, Mary and her half-sister Claire Clairmont made an excursion to Chamonix. Percy Shelley wrote to his friend Thomas Peacock describing their journey. His words were published alongside Shelley's poem Mont Blanc in History of a Six Weeks’ Tour, 1817.

Mont Blanc was before us […] Pinnacles of snow intolerably bright […] shone through the clouds at intervals on high. I never knew - I never imagined what mountains were before.Percy Shelley, writing to Thomas Peacock

All men hate the wretched; how, then, must I be hated, who am miserable beyond all living things!The Creature to Frankenstein on the Sea of Ice, chapter 10

Straight away, Percy saw the potential of Mary’s short story. He encouraged her to expand it into a novel. Later that summer they went to Chamonix, another location in Frankenstein. In September Percy and Mary returned to England. In December, Percy’s wife, Harriet, was found drowned. She was pregnant with her third child. Percy married Mary a few weeks later.

Frankenstein was published in 1818, and quickly became a bestseller. ‘The tale, though wild in incident, is written in plain and forcible English, without exhibiting that mixture of hyperbolic Germanisms with which tales of wonder are usually told,’ wrote Walter Scott. Mary bore Percy two more children, but in 1822 Percy drowned, aged 29, on a voyage across the Med. In 1824, Byron died, aged 36, of malaria in Greece.

Mary devoted the rest of her life to her husband’s posthumous reputation. She edited numerous collections of his poetry, but her father-in-law forbade her from writing Percy’s biography. She never remarried. Three of her four children predeceased her.

She wrote several other novels, but nothing she wrote subsequently matched the success of Frankenstein. As she recalled in later life, ‘It was the offspring of happy days, when death and grief were but words.’ She died in 1851, aged 53, the last survivor of that ‘year without summer’ in the Villa Diodati. These two exhibitions beside Lake Geneva bring that momentous summer back to life.

- Frankenstein, Creation of Darkness is at the Fondation Martin Bodmer in Geneva until 9 October 2016

- Lord Byron, Le Retour is at Chateau de Chillon in Montreux until 21 August 2016

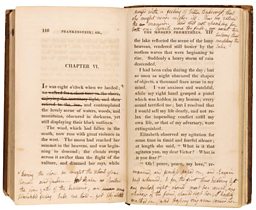

Mary Shelley's first edition

> View large image in new browser window

This copy of the first edition, known as the 'Thomas copy', is the only one containing annotations in the author’s hand which has been preserved. Mary Shelley presented it to a Mrs Thomas of Genoa shortly after the death of Percy Shelley in 1822. The annotations consist of changes which Mary Shelley envisaged, some of which were made in later editions / Pierpont Morgan Library, New York

Le Monstre et le magicien, 1826

Platel (drawing) et Cheyère (lithographer) | Mr Cooke in the role of the monster (Théâtre de la Porte St-Martin, 3rd act), Paris: Genty, 1826 / Bibliothèque Nationale de France, Paris / Le Monstre et le magicien, by Antony Béraud and Jean-Toussaint Merle, was among the first theatrical adaptations of the novel by Mary Shelley. It was produced in Paris in 1826. The role of the monster is played by the London actor T.P. Cooke, who had earlier played the same role in Presumption, an English version. This illustration of the script shows the moment where, in the novel, the creature kills William, the little brother of Victor Frankenstein.

Frankenstein

Read more

More from Books

-

![]()

#Vote100Books

Seven must-read novels by female authors.

-

![]()

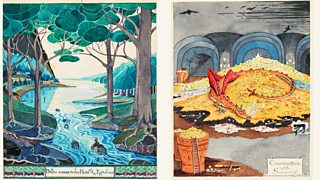

Middle-earth in colour

Tolkien's own illustrations of his fantasy universe.

-

![]()

Neil Gaiman

The author picks his three favourite works of science fiction.

-

![]()

Publishing design cliches

Judge these books, and their genres, by their covers.

More from BBC Arts

-

![]()

Picasso’s ex-factor

Who are the six women who shaped his life and work?

-

![]()

Quiz: Picasso or pixel?

Can you separate the AI fakes from genuine paintings by Pablo Picasso?

-

![]()

Frida: Fiery, fierce and passionate

The extraordinary life of Mexican artist Frida Kahlo, in her own words

-

![]()

Proms 2023: The best bits

From Yuja Wang to Northern Soul, handpicked stand-out moments from this year's Proms