“Gali ke modh par soona sa koi darwaza,

Tarasti aanknon se rasta kisi ka dekhega

Nigah door talak jaake laut aayegi...”

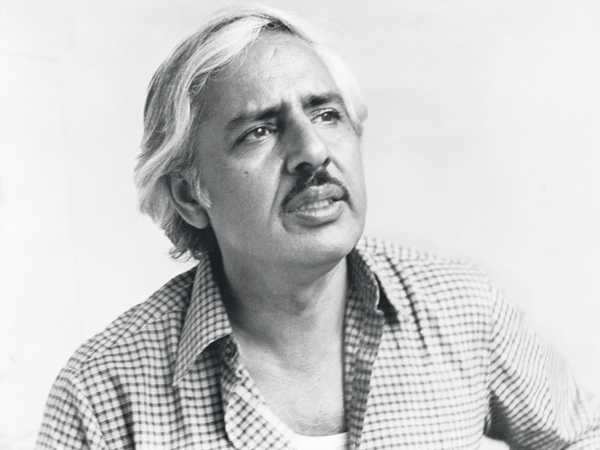

When Sagar Sarhadi directed the evocative Bazaar (1982), little did he imagine that Bashar Nawaz’s lyrics Karoge yaad toh har baat yaad aayegi... would eventually become his sundown sonata. The 80-plus writer-director lives in the nondescript bylanes of Sion. A door left ajar, almost in perennial anticipation, leads me inside his unpretentious home. A thousand dust-impinged books, unidentified knick knacks, random pieces of furniture, casually strewn trophies – even a Hum Sab Ghalib citation tussle for co-existence. His domestic help has deserted him, he says, even as he graciously offers me tea.

“The house misses the presence of a woman,” he says in mock jest. “I tell my friends there should be a woman in your home. A woman is maternal, she nurtures you. A woman who looks after you, smiles at you, fights with you is necessary in the periphery of your life.” He confides battling depression a while ago. Hence, he ventures out to nephew and director Ramesh Talwar’s office each day. “Heartbreak and loneliness takes its toll. Twenty four hours in the house will make you mad. To reach Rameshji’s office, I change two to three trains every day. After which I take a bus. All this movement cuts the depression. I see faces, I see trees, I interact with people in the office... it feels good.”

Refugee for life

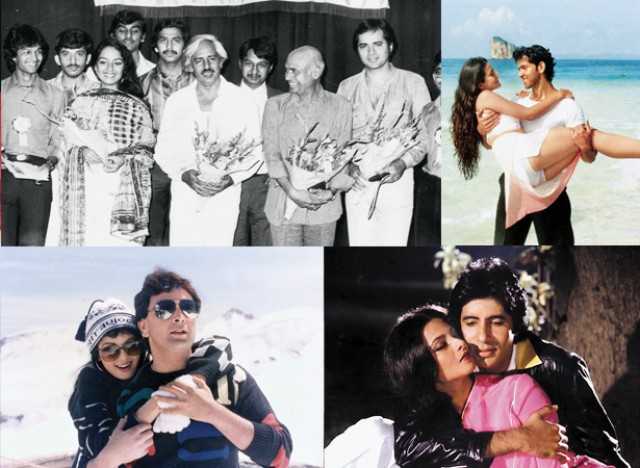

It’s not that Sagar Sarhadi, known for his dialogue and screenplays in love sagas like Yash Chopra’s Kabhi Kabhie (1976), Silsila (1981), Faasle (1985) and Chandni (1989), among others, has not enjoyed the warmth of relationships. But sadly, the holocaust of the Partition during his childhood, ensured he remain an ‘emotional’ refugee through life. Overnight, like million others, his family was driven out of Baffa in Pakistan and dumped in Delhi. Later, they came to Mumbai. “Bedar (displaced), beghar (homeless), bhookey (hungry)... we had lost our home, our fields. That sense of being uprooted never left me and the negativity coloured the way I viewed marriage later.” In Mumbai it was a subhuman existence. “We lived in a single room in Koliwada with my elder brother (Ramesh Talwar’s father), my Bhabhi (a fine woman, she nursed me when I lost my mother as an infant) and his children. There was no bathroom. We walked three kilometres in the salt fields to relieve ourselves.” He continues, “Once my father sent a postcard informing that he had fixed ‘Azeezun Gangasagar Talwar (his actual name) ki shaadi’ with a particular girl back home. I scribbled 120 gaalis (abuses) on a postcard and sent it to him. I said you get married, not me. He cried on reading it. Then, when he came to Mumbai, I explained the situation and he understood.”

What also influenced his radicalism was his affinity towards subjects like Marxism and Psychology. “That’s a deadly combination! Noted psychologist Wilhem Reich said that no marriage lasts more than four years. And that the couple ends up looking like brother and sister. Through the years, they talk like each other, behave like each other. Romance vanishes. It becomes a matter of fact existence more so after children,” he explains why he didn’t believe in marriage.

Besides he wasn’t financially sound. He earned just about ` 50 a month. “I feared I wouldn’t be able to look after my family. I’d have to leave the profession and become a clerk.” And Sarhadi didn’t want to give up his rendezvous with great minds and thinkers. He got a chance to understand literary greats like Ismat Chugtai, Kaifi Azmi, Sardar Jaffrey, Faiz Ahmed Faiz, Kishen Chander and others during my stint with IPTA. Along the course, his Urdu plays like Bhagat Singh Ki Waapsi, Khyaal Ki Dastak, Raj Durbar and Tanhai won much applause.

WOMEN & WOES

He insists he’s lived a ‘rich’ life and has had several relationships. “Romanticism is in my veins. I have had around 20 affairs. Also, I never left the girls, the girls left me,” he smiles. “They wanted to settle down. But I was against marriage. One of them was a theatre actress. She was even willing to ‘live in’ with me. But her family got wind of it and locked her up in a room. Somehow, six months later, she managed to sneak out and came to meet me. She sobbed and said that she was kept under scrutiny all the time and that she would soon be married off. A person waited on her even when she visited the washroom. I never saw her again.” His short story, Udaasi was based on this oppression of women. “Being left alone today is the high price I paid for idealism. A friend rightly remarked, ‘You can remain with your idealism. A girl won’t’.”

YASH CHOPRA & I

The pressing need for survival made him collaborate as dialogue and screenplay writer with the late Yash Chopra. He even wrote the dialogue for Basu Bhattacharya’s Anubhav (with Kapil Kumar, 1972), Raj Kanwar’s Deewana (1992) and Rakesh Roshan’s Kaho Naa... Pyaar Hai (2000). His short story Raakha was made into the superhit Noorie (1979). But he credits Yash Chopra for bringing him in the limelight. “As a screenplay writer, my name appeared before that of lyricist Sahir Ludhianvi and music composer Khayyam in the credits of Kabhi Kabhie. Sahir saab was upset that the name of someone so junior preceded his. He said, ‘Picture nahin chalegi’. Unka temperament aggressive kism ka tha. But Yashji did not waver.” He goes on, “I owe my popularity to Yashji. He made me a star. Unhone mujhe hatheli par rakha. He treated me with respect and would send the car to pick me up. After Kabhi Kabhie he treated me to a holiday in London. I was put

up in a five-star suite for 23 days.”

Sarhadi shares a fondness for Amitabh Bachchan as well. “Amitabh may have done more work with Salim-Javed but he held me in great respect. Once on the set of Kabhi Kabhie, out of affection, when he was pressing my legs he remarked, ‘Bahut gham dekhein hai aapne’. Maybe he could sense my loneliness. Also, Amitabh had a sharp memory. He’d say, ‘Padh kar sunaiye. While I read out the dialogue, he’d merely say, ‘Hmmm… Hmmm… Hmmm’. Such was his concentration that he grasped the dialogue easily.”

BAZAAR

Restlessness and an irritation with the industry, which doesn’t believe in paying writers well, pushed him to take to direction. And Bazaar, a lament against trade of young Muslim girls in Hyderabad to wealthy and much older Arabs, was born. “Bazaar emerged out of self-analysis.

I moved beyond romance and wrote a realistic, social subject.” The going wasn’t easy because he had never assisted anyone before. Also to convince stalwarts like Naseeruddin Shah and Smita Patil was not a cakewalk. “We first shot for eight days in Mumbai during which I sensed that Smita was not happy with me. The next day we were to leave for Hyderabad. I feared she wouldn’t join us. But before leaving the set, she told me, ‘You’re one of the fine directors I have worked with’. I was so relieved.” He adds, “Also Farooque Sheikh, after every shot would say, “Mashallah Mashallah!” That boosted my confidence.”

Naseeruddin Shah suggested Supriya Pathak’s name for the role of the simple Hyderabadi girl. “Supriya was a gol matol si ladki. I wanted just that.” Sarhadi recalls the dramatic ‘Boli lagaao’ scene shot with Naseer in the dead of the night. “I had thought that an entire night would be needed to shoot that. But he finished it within

two hours.”

He gives insights into the maverick actor that the late Smita was. “Smita had to trust you. Or else she could kill you. She was temperamental. She was fearless. Unfortunately, she was also kaan ki kachchi and a simpleton. Some director friend told her that in Bazaar she had no role. ‘You go by the train and you return in it,’ he said. She was upset and refused to dub. I thought of getting another dubbing artiste but just then she thankfully walked in.”

Bazaar is also remembered for its immortal music. “Writing lyrics for the film would not have lent it gravitas. So we culled out traditional poetry of classical poets. We took Dekh lo aaj humko from a 200-year-old book, Zehre-E-Ishq by Mirza Shauq. Dikhaye diye yun is written by Mir Taqi Mir. Phir chiddhi raat is by Marxist poet Makhdoom. And Khayyam saab worked his eternal magic!” Initially, Bazaar did not find takers but when released, it went on to mesmerise audiences. “It was in its 18th week, when I went to watch Bazaar in a theatre in Hyderabad. As the song Dekhlo aaj humko jee bhar ke played, women seated in the special ladies section, began sobbing. I just left the theatre,” he recalls. Bazaar was made in a shoestring budget of 13 lakhs. “After the release, we sent a cheque of 11,000 to Supriya and 40,000 to Smita,” he smiles.

NO REGRETS

Next he had planned Tere Shaher Mein, which cast Naseeruddin Shah, Smita Patil, Deepti Naval and Marc Zuber, a film around justice gone wrong. “The producer took finance from a Delhi financer. The producer could not pay back. So the financer took away the reels. The film never saw a release.”

Sarhadi may have lost out on people, but he’s not lost the capacity to dream. “I want to make a film on freedom fighter Ashfaqulla Khan,” he says pointing to his research on the martyr. Bazaar 2, a love story of a journalist and a pick pocket, is also a dear subject. “Bahut paaya, ussey bhi zyaada khoya. Yet I have no regrets. I’ve lived like

a badshah. I have lived it all... the pagalpan, the masti. Haraami hoon main. I’ve had enough alcohol. But now the body has given up. Phir jeeunga toh yehi haraamzaadi karoonga.”

SHOW COMMENTS