The powerful pan-Asian message of woodblock printing

Invented in China, perfected in Japan and widely appreciated elsewhere,art made using woodblocks is a reminder of a world beyond technology, artist and old China hand Ralph Kiggell, a Bangkok-based Briton who's often in Hong Kong, tells Mark Footer

I was born abroad, in Northern Rhodesia (now Zambia), and so were my parents. My father was born in Africa and my mother in India. We returned to England when I was four. I recently found a drawing I had done when I was six or so of a temple and mountains and a path with a signpost saying "Japan". As a child, I used to write pretend Chinese characters and colour in pictures of people from around the world, so I've always been fascinated by what lies beyond my own culture.

Malaysian punk artists use radical woodcuts to assert natives' rights

When I left school I couldn't decide whether to study art or not, but I chose, instead, to learn Chinese at the University of London. In 1980, we had the chance to go to Beijing for one year as part of our course. The first sight of Beijing was of a flat, dusty brown city crammed with people on bicycles. TV only seemed to show the trial of Jiang Qing (Mao Zedong's fourth wife) and the Gang of Four. Everyone asked me if London was as foggy as it was in , which is ironic when you think of Beijing now. Our curiosity for everything Chinese was equally matched by their curiosity for us. That year in China was a massive adventure. I was back in China from 1983 to '85, teaching in Kunming, in Yunnan province, which was another wonderful adventure.

Everyone asked me if London was as foggy as it was in Oliver Twist, which is ironic when you think of Beijing now.

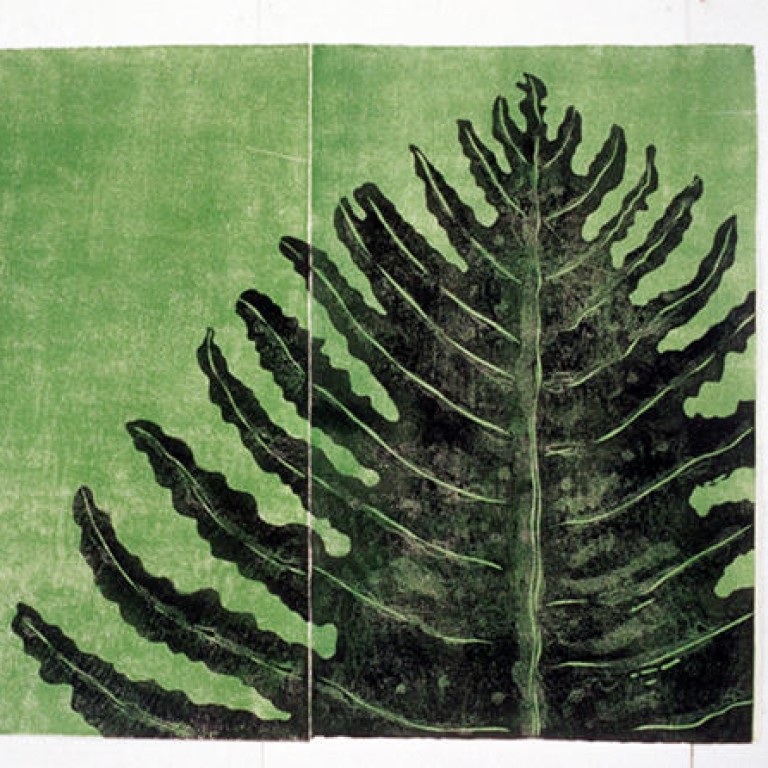

I began to study woodblock printing on and off when I went to Tokyo in 1990. I won a scholarship in 1995 to study a master's degree. The more I practise woodblock printing, the more I understand how the technique can be continuously experimented with and extended. Woodblock printing uses water-based ink and everything is done by hand, without presses. It's the time-honoured process that was invented in China - along with ink and paper - and spread to Japan. It's also non-toxic. The Japanese love visual information and have a deep sense of graphic design, which is what attracted me to woodblock printing: the startling arrangements of shape and colour that you might see, for example, in Kitagawa Utamaro's portraits of courtesans. In Japan, there is also a great respect for craftsmanship and materials.

In 2004, I had a two-month residency at the Sichuan Fine Arts Institute, in Chongqing, one of the six or so major art schools in China and the only big one in the southwest. I hadn't been back to China for any extended period since the late 1980s. Chongqing looked almost sci-fi. At the art school, I gave classes in my woodblock-printing techniques learned in Japan, and we compared these with the printmaking techniques that had evolved in modern China. I would say that traditional woodblock printing in China had lost its way a little at that time, because of the communist preference for black and white oil-based methods to tell a story clearly. Things are changing now.

I lived in Hong Kong from 1985 to 1990 - in Victoria Barracks before it was a park, then on Cheung Chau, in Mid-Levels and, lastly, on Hollywood Road - and I always try to visit regularly. As an artist, I'm particularly fascinated in the islands, hills and bays, and the toing and froing of boats in the harbour. I love to compare what you see now with the old China trade paintings. A few years ago, I did a big mural at the Ladies Recreation Club in Hong Kong, based on one of my swimmer prints, and I've collaborated on a children's book, . Recently, I've been doing prints of dramatic Hong Kong bays.

Baoan, in Shenzhen, is where the modern Chinese print movement began in the 1930s, so the local government there has invested a lot of money in the Guanlan print complex, which includes the print base and an amazing print museum. In December and January, I was one of several resident artists there, including Chinese, Bulgarians and a Finn. I worked with artist-technicians in the woodblock section, mainly in oil-based techniques, mixing in a bit of lithography. We all stayed in these wonderful houses in an old Hakka village, but the studios are modern with all the best facilities.

These days I'm mostly based in Bangkok, where I have a studio and give workshops at colleges and schools around the city. Bangkok has quite a few galleries and the art scene there has become more varied and provocative. As a non-Thai in the city, I would like to see a better community of artists and a wider understanding of the arts, not only as something you might buy and put on your wall, but as a voice of social change.

I'm working slowly on a book of 12 prints that will describe the palaces and gardens of Chengde, the summer retreat of the Qing emperors. That should be finished by next year. I've just finished an exhibition in Phnom Penh. In Hong Kong, I hope to show some of the seascape prints I did in Guanlan. And I'm helping to organise a big conference about woodblock printing in Hawaii for 2017. I see woodblock printing as much more than just an art form or a technique. It carries powerful messages. Wood reminds us of what lies, or should lie, beyond the city and technology.