What made CJI TS Thakur cry in front of PM Modi

Why the judicial system has broken down and how to fix it.

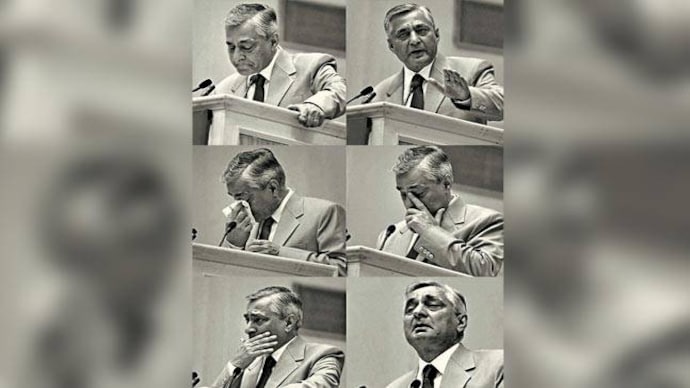

Oh, poor litigant, people languishing in jails." His voice trembled a little. "In the name of development and progress, I beseech you," he looked at Prime Minister Narendra Modi, "to rise to the occasion and realise that it's not enough to c-r-i-t-i-c-i-s-e." The sentence trailed off, pauses between words got longer. Heads jerked up and eyes widened. It was the sound of a man struggling to keep his voice from betraying his feelings. But it wasn't just any man. The 43rd Chief Justice of India, Tirath Singh Thakur, stood on stage, jaws tight, eyes averted, reaching into his pocket for a handkerchief to mop his eyes. The silence inside Delhi's Vigyan Bhavan on April 25 was absolute, people exchanged glances in shock and dismay. The prime minister looked on intently from his seat on the stage.

It actually took all of 37 minutes and four seconds for the CJI to force the nation to sit up and pay attention. Exactly the time in which judges around the country conclude 15 hearings and decide seven cases, on average. That's because judges in the busiest courts spend an average of 2.5 minutes to hear a case and about five minutes to decide one. Not because our judges are in a hurry. But because they can hardly devote more time to a case, such is the shortfall of judges in the country.As mentioned in the Lok Sabha on March 3, 2016, 44 per cent judges are missing in high courts, 25 per cent in subordinate courts and 19 per cent in the Supreme Court.

Four noble truths

At the heart of the CJI's address were four strands of arguments: that judges are overwhelmed by the load of litigation; judicial vacancies are not being filled up; the appointments procedure is getting stuck at the level of the government for obscure reasons; and that without the wheels of justice turning smoothly, the common man will suffer the most. The Law Commission of India has been crying itself hoarse since 1987, along with 15 successive CJIs in the last 29 years, about the need to increase the number of courts and judges drastically for justice to have any real meaning. But it had stopped hitting the headlines. With the CJI's emotional tribute to the cause of justice, it has taken centrestage again. "Getting emotional is a weakness," said the CJI at a press conference later that day, "one should not get emotional?but (one has) some commitment towards the judiciary."

"It's deliberate negligence from governments that has pushed the judiciary into such a state of scarcity," says eminent jurist Ram Jethmalani. "The judiciary accounts for just 0.5 per cent of the budgetary allocation." The CJI's outburst caught the prime's minister's attention. Modi, who was not scheduled to speak on April 25, took the microphone to say he understood the CJI's pain. "Let us see how to move forward by reducing the burden of the past," he declared, inviting the CJI and his senior judges for a closed-door meeting with him and his Cabinet colleagues.

Tough tactics

The CJI has taken Supreme Court lawyers by surprise. Soft-spoken and patient, Justice Thakur is also known to be fiery and fearsome. Lawyers discuss countless occasions when he has ticked off the high and mighty of the nation: "Senior lawyer and Union minister Kapil Sibal was appealing for the release of Sahara chief Subrata Roy and the CJI told him, 'Argue on facts and law, don't lecture us every time'," they cite; they also talk about his tough stand on the BCCI reforms, the Saradha scam and even the PM's pet project of cleaning the Ganga. "Your action plan will not clean Ganga in 200 years," he famously told off the government solicitors.

That reputation for tough dealing has created confusion and difference of opinion down the spectrum. Some lawyers express deep disappointment: "The CJI is extremely important in our Constitution. He should not have broken down before the PM." Some can't deal with the shock: "The CJI is known to be very tough, with a strong command of the courtroom. He can make senior lawyers sweat." Some say that the Supreme court could have issued a writ of mandamus to the government, to enforce its duty. Others point out how that would have been perceived as "judicial overreach". Yet others believe it was a tactical posture: "We need judges. Period. With the Modi government blocking all efforts of judicial reform, especially after its defeat over the NJAC, the only way is to call public attention to a crying need."

Spectre of overreach

Strangely, it was a moment that added the finishing touch to a tumultuous year between the Modi government and the judiciary. It was exactly on this stage last year, on April 5, that the showdown started. It was here that the chief executive of the nation, Prime Minister Narendra Modi, had taken the opportunity to rap the judiciary on the knuckles and in public. "While the Indian judiciary at all levels is getting powerful, it is necessary that it also becomes perfect to live up to the expectations of the people," he had said.

In a way, it was an incident that triggered off months of flashpoints and face-offs between the two pillars of Indian democracy, finally leading to the failure of the PM's flagship legislative endeavour: the six-member NJAC, aiming to replace the collegium system of senior judges cherry-picking brother judges by a commission which would give the executive the power to influence appointments in higher courts and all ethics-related issues. "The government may have accepted it, but the clash between the judiciary and the political class is clearly not over," says Upendra Baxi, professor of law at the University of Warwick, UK.

It's not just the NJAC, but the thin line between judicial activism and judicial overreach that will continue to haunt the judiciary unless it gets its act together, and fast. There's a feeling that judges have wrapped themselves in a cloak of inviolability. As eminent jurist Fali S. Nariman says, how are they appointed? Why are they appointed? What are their shortcomings? How are these dealt with? "Ask and they'd say, 'It's none of your business. We know what is best for the system'," he says. At the root of it is, of course, the collegium system. The allegation of overreach also lies in the apex court's penchant for driving investigations and prosecution. That focus on investigating agencies is often seen as systematic and deliberate, resented enormously by the government of the day. The failure of the NJAC was seen as a "tyranny of the unelected"-in the words of Union finance minister Arun Jaitley.

The CJI knows that. On December 2, 2015, as he took over the reins, he had said: "The judiciary is facing its greatest challenge in recent times." The striking down of the NJAC Act gave people the impression that the judiciary had claimed for itself the power to appoint judges. It needed to come up to their expectations, fill up vacancies in courts across the country. "Chief justices and judges of the Supreme Court, while selecting people for elevation, must go strictly by the beats of their conscience."

A few fixes

Focused on streamlining judicial appointments, the CJI had set up a constitutional court in January to reduce the burden of pending cases that involve interpretation of the Constitution. By February, however, things were clearly not going quite right and the CJI was calling for "an audit of the government's performance", blaming it for "sitting on" decisions of judicial appointments. From March, the CJI started questioning why the Intelligence Bureau should take months to verify judges recommended by the Supreme Court collegium. "Why can't the Prime Minister's Office ask the IB to send its report within 15 days?" the CJI asked on April 9, pointing to proposals for the appointment of 170 judges pending with the government for months, although 90 per cent were sitting additional judges.

The winter session of Parliament that had passed the Commercial Courts, Commercial Division and Commercial Appellate Division of High Courts Act, 2015, to transform the manner in which commercial cases are dealt with and bring down delays-has been a thorny issue: without separate manpower and infrastructure, the courts are being designated out of existing ones-which already have far too many vacant posts.

Another solution could be for the Bar Council of India to utilise judicial academies optimally. Academies are being set up in different states for training judicial officers and lawyers, set the standards for legal education, ensure law students from all law colleges have access to academic facilities. A separate judicial administrative corp can also supply much-needed manpower. The apex court has set a target of taking the combined strength of the judiciary to 30,000 in the next five years.

The key to judicial reform lies in taking initiatives, for instance, to quell the ease with which adjournments can be secured in courts. Shifting hearing dates repeatedly causes delay in civil cases. Limiting reasonable grounds for adjournments, some inhouse rules along with strict directive from the CJI, can reduce pendency considerably.

Introducing modern methods and technology can also solve delays to a large extent. From service to summons to bail, everything in the justice system is manual. Fifty per cent of judicial delay is due to non-service of summons, arguments over validity of summons, proper identification and so on. It's old-fashioned ethos, and not vacations, that keeps the courts clogged.

What about increasing work hours? The Supreme Court works for 193 days, high courts 210 days and trial courts 245 days a year. In contrast, in the United States, courts never close for summer break, just as in some European countries, such as France. The Supreme Court of Canada goes on vacation for just 11 days. In Britain, the court closes for 24 days in a year. But will our higher judges be able to handle the work pressure without down time?

Being a judge is "a privilege, a pleasure and a duty", wrote a legendary judge once. A distressed CJI clearly doesn't bode well for the brotherhood of Indian judges, or for the nation. The whys and hows will be debated for years. Meantime, an exclusive sharing of survey data by Bangalore-based legal resource, Daksh India, with india today, gives some clue to that puzzle.

Also read: