A front row seat at the theatre of war

Staff at Dublin's Abbey Theatre, from actors to stagehands, played a role in the Rising

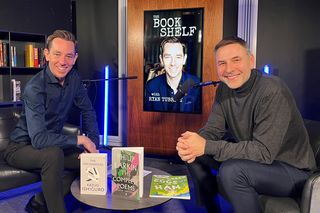

Show must go on: Archivist Mairead Delaney carefully holds an Abbey Theatre programme from Easter Monday 1916. Photo: Fergal Phillips.

On Easter Monday 1916, Abbey Theatre manager St John Ervine had a front row seat for the real-life drama unfolding on the street outside, as rebels marched the short distance from Liberty Hall to the GPO.

Ervine was preparing for the matinee of Kathleen Ni Houlihan, the play by WB Yeats and Lady Gregory depicting Ireland as an old crone transformed into a beautiful young queen when men die for her.

As the first shots rang out from the GPO at about 1.15pm, Ervine realised the show would go on - but not in the confines of his beloved theatre.

In the ultimate case of life imitating art, this production was happening for real, and the martyrdom of its leading men would soon garner a global audience for a tiny nation taking on the might of the British empire. As Kathleen proclaims in the play, "The people shall hear them forever."

"Ervine, a staunch Unionist, shared none of the nationalist sympathies of many of his players," says Abbey archivist Mairead Delaney. "Fearing Kathleen would play into the hands of the rebels and further incite the people, he cancelled all performances that week."

First on the cast list of Kathleen Ni Houlihan was Sean Connolly, who would go on to mark other 'firsts' as he led his troop of 10 men and 10 women to Dublin Castle, the headquarters of British administration in Ireland.

He was the first rebel to kill a fellow Irishman, Constable James O'Brien, at the castle gates, and the first of the rebel fatalities when he in turn was shot dead on the roof of City Hall. He died in the arms of fellow Abbey actor Helena Molony, a prominent republican, feminist and labour activist who'd spent the previous night in Liberty Hall with a parcel of Proclamations under her pillow.

The company's original leading actress, Maire Nic Shiubhlaigh, was a key member of Cumann na mBan, and took charge of the women in Jacob's biscuit factory, while actor Arthur Shields fought in the GPO. Arthur's brother William was better known by his stage name, Barry Fitzgerald, who went on to win an Oscar for his role in Going My Way.

"On Easter Sunday Arthur returned from the Abbey's English tour," says Mairead. "On Monday, he got permission to drop off a script at the Abbey before reporting to James Connolly at the GPO. It's believed to have been the script for The Spancel of Death, a story of witchcraft by Mayo playwright TH Nally, which was to premiere on Easter Tuesday.

Actors were never given an entire script in those days, as it was too expensive to print. Instead they were given only their part.

"After the Rising, Arthur served time in Frongoch prison in Wales, but he was back treading the boards that September, and went on to become a Hollywood star in the 1930s. To this day, The Spancel of Death has never performed at the Abbey and is now known as 'the play that never played.'"

But it wasn't just the Abbey actors who were active in the Rising; many behind the scenes were also involved. Prompter Barney Murphy fought in the Four Courts, and usherette Ellen (Nellie) Bushell, was stationed at Jacob's factory, as was stage hand Peadar Kearney, who wrote the national anthem.

Between the nightly curfew imposed immediately after the Rising, and the fact that many of its key players were in prison, the Abbey Theatre didn't reopen for some weeks and when it did, relations between the manager and his players were strained.

It wasn't helped by Ervine announcing his biggest regret of the Rising was that the British naval ship the Helga didn't train her guns on the Abbey and blow the theatre sky high.

"That was partly because the British Government would issue compensation for buildings damaged during the insurrection and owners could use the money to expand their premises. Apart from a couple of smashed windows, the Abbey remained intact, perhaps infuriatingly for Ervine."

When he put actors on notice for not turning up for rehearsals, they went on strike and the company temporarily disbanded. Ervine enlisted with the Dublin Fusiliers and lost a leg while fighting in Flanders.

In her research into the history of the theatre, Mairead says she became intrigued by the preponderence of poets, playwrights, actors and behind-the-scenes staff who were revolutionaries at that time.

"I wonder how much of what they saw here might have helped to radicalise them. Part of the mission of the Abbey Theatre since it opened in 1904 was to put the deeper thoughts and emotions of Ireland on the stage, and I wonder if that influenced the people who worked there. Did art inform their political beliefs?"

Undoubtedly, tales of heroic nationalism were part of the cultural revival that went hand in hand with the political revolution of the time, but nobody could have foreseen the accuracy of some productions put on years before the Rising took place.

"Rebel leader Thomas MacDonagh's play, When the Dawn is Come, which premiered in 1908, was set in the future, at a time of insurrection, and featured seven captains of the Irish Insurgent Army," says Mairead.

"And in 1913, a play ironically called The Post Office translated by Yeats from Indian poet Rabindranath Tagore's work, dealt with themes of liberation from captivity.

"Conscious though I am of looking back with 20:20 vision, you have to wonder if it was with some kind of prescience that these plays predicted such detail of what was to happen years later."

Join the Irish Independent WhatsApp channel

Stay up to date with all the latest news