Four definitive exhibitions in New York during the 2015-16 season, when taken together, make a strong case for reconsidering Postminimalism as being second only to Conceptualism as the 20th-century movement most substantively informing non-pictorial artistic developments in the first decades of the 21st Century. It's not that Postminimalism is to be congratulated for its renewal today, or that there was any doubt that Conceptualism is the motivating force for all art from the Impressionists on, as much as it is a matter of discerning what in the legacy of the original movements of Postminimalism and Conceptualism are vital to artists working today. It is also a matter of clarifying in the historical shows of those artists who worked outside the West who it is that developed their own indigenous innovations compatible with Postminimalism and Conceptualism and those that grew as the effect of crossculturalism.

The season began with just such a crossculturalism manifest in the exhibition, Autobiography of A Line, a small but compelling exhibition at the Dominque Levy Gallery, from September 10-October 24, 2015, consisting of sparse, hanging and jointed-wire sculptures by the late German-Venezuelan artist Gego, the name by which Gertrude Goldschmidt (1912 - 1994) became known internationally in the 1960s. Another show of Gego's most renowned work known in Spanish as her Reticuláreas are scheduled this May at Dominque Levy, London. (This commentary will be expanded to reflect that show for those who care to check back.) In March of this year, the first American retrospective of the Minimalist/Postminimalist drawings and prints by the late Indian artist, Nasreen Mohamadi, opened spectacularly at the new Met Breuer Museum in the former Whitney Museum building on Madison Avenue. The two exhibitions clearly indicate that Gego and Mohamedi were already exploring their own hybrid postminimalism before the appellate became the international signifier of a movement, or anything resembling an identifiable international style known for its preponderant employment of materials derived from industrial manufacturing and architectural industries.

In between these two historical shows, a small but impacting two-person exhibit by Ruth Hardinger and Kara Rooney was hosted by the Five Myles Gallery, situated in the vicinity of The Brooklyn Museum, and curated by The Brooklyn's former chief curator, Charlotta Kotik. Kotik had assembled numerous shows by Postminimalists and Conceptualists since the late 1970s, when she then was a curator at the Albright-Knox in Buffalo. The Five Myles' pithy show title,Trace Matter, could have complimented any showcases known for promoting Postminimalist and Conceptualist exhibitions in the 1970s. But it's timing being concurrent with the first recent American exhibition of Gego's sculpture at Dominique Levy was fortunate, as is the concurrency of Ruth Hardinger's solo exhibition in March and April at the Amelie A. Wallace Gallery of the State University of New York (SUNY) at Old Westbury with the Nasreen Mohamedi show at the new Met Breuer for reprising postminimalist and conceptual issues not engaged with such enthusiastic zeal and theoretical acumen for decades.

The stature of Gego and Mohamedi on their respective continents notwithstanding, for most American and European culturophiles the art of both of these masters is as new as that of Hardinger and Rooney. In encountering them together we may consider them on something of an even keel at this outset, not so much to anticipate a renewed movement -- their concerns are too diverse for that -- but as a joint capitulation of legacies and inheritances that span six decades in their reformation. What all four artists simultaneously introduce is the chance to legitimately assess how Postminimalist and Conceptualist art has yielded what may be the first truly global movements. In fact it is likely that many reading this can add there own list of global artists celebrated by exhibitions in their regions for an art that evolved from either or both Postminimalism and Conceptualism.

In New York, recent relevant exhibitions that arguably renew and extend include those of the Ghanaian-Nigeria-based sculptor, El Anatsui, whose site-specific sculptures have become a favorite subject of many art writers for his ingenious fusion of African traditional arts (weaving and metal work) with an eye and hand for crafting his culture's version of postminimalist aesthetics, replete with a postcolonialist critique intersecting international identity politics and the exploitation of Africa by global capitalism. El Anatsui's woven "threads" are made from industrial materials that the artist finds in the sprawling African dump sites deposited by the world's industrial nations. El Anatsui's recurring shows at the Jack Shainman Gallery in New York since 2008 culminated in his much lauded-Brooklyn Museum show in 2013 and his hugely popular 2015 installation at the Metropolitan Museum. Also in 2013, MoMA's retrospective of the Brazilian artist Lygia Clark provided yet another art historical argument that the roots of Postminimalism (and in her case Minimalism) are as global as they are North American or European.

Whether or not we want to persist in calling the work of younger generations and non-Western artists 'postminimalist' (small 'p' when not referring to the original movement) is a worthy debate, given that it is now some fifty years since the term was first coined by the art critic Robert Pincus Witten for a generation of artists largely centered in New York. The most canonical of the early movement are all well known from their representation in museums and art history books around the world: Eva Hesse, Robert Smithson, Richard Tuttle, Bruce Nauman, Richard Serra, Barry La Va, Alan Saret, Keith Sonnier, Lynda Benglis, Joel Shapiro and Gordon Matta-Clark. It began as a relatively small coterie of artists who all knew one another. Although Hesse, Smithson and Matta-Clark died within a decade of introducing their paradigmatic work, all of these artists separately and together left a formidable impression on the work being made from that time and up through today to the point that it is time that we recognize just how great an extent the movement grew into a ubiquitous and capaciously-subsumptive choice of artmaking for three successive generations. Especially for those arists who relish working with a diversity of chance-accidental processes and with materials associated today as much with the principles of spontaneity and material improvisation that opens their work to multiple literal and metaphorical interpretations, or to no interpretation at all.

Until there is a better name coined for the practice of the new generations of artists who favor formal and contextual diversity (it truly is a generation of Post-Postminimalists, but that name will never do), looking back to Postminimalism ideologically and materially situates the art of the four artists here discussed and numerous others not originally associated with the movement. In expanding the terrain of Postminimalism we are attesting that art history isn't simply a record of the period movements and paradigms that defined the zeitgeist artistic productions and ideologies for each generation or epoch. It is also a record of the interstices between these movements and zeitgeists. Interstices within which there is no one or clear movement dominating artistic production yet may include any number of remnant movements of the past, even some intimations of yet-unrealized future movements overlapping simultaneously while sharing characteristics that no other movement vitalized. That Postminimalism and Conceptualism have continued to evolve and expand their parameters in large part explains why there has not been a truly new and formidable art movement since the 1980s, when the short-lived and small practices of Neo Geo and Pictures spawned a period of ironic posturing that we then called Postmodernism.

In the absence of a new and galvanizing movement since, the current generations of artists active globally are enjoying an extensive interstice, one in which the earlier art movements are being salvaged by artists of various cultural origins to extract what potential the former movements had either left unrealized during the movement's heydays. And yet there is no prior movement of sculpture that can compete with Postminimalism's assimilation of diverse and often refuse materials. While the earlier Dada and Surrealist inventions of the assemblage come close to Postminimalism, and are truly its parentage, 'assemblage' refers only to the collection and assembly of elements. It doesn't represent the modeling and gesticulation, colorization, serialization, incorporation of nature, scattering of objects across indoor and outdoor spatial fields, and especially the care given to placement, linearity and interval, in the Postminimalist installation that defines much abstract and figurative work being made today.

Proof that artists and their audiences are today enjoying a prolonged interstice between movements is that Postminimalism, with it open systems, survives today while Minimalism, with its narrow and closed systems does not. Minimalism was so monumental, so dependent on the labor and expense of large teams to ship, install and dismantle art that Minimalism became symbolic of the corporate, impersonal world of high finance that alienates many younger artists in the Occupy Age. Postminimalism, while lending itself to grand statements on occasion is altogether a more personal enterprise. Whereas Minimalism was the product of a virtual assembly line, Postminimalism was and remains a kind of cottage industry.

It might also seem that it would be more accurate that this commentary be called Reprising Postmodernism and Conceptualism, since Hardinger and Rooney, among many other artists of their generation, make each object the subject of a contextual scheme, and for Hardinger an eco-political one. But Conceptualism has never disappeared from the contemporary art scene, having survived the generational shifts in production and discourse since it was introduced in the 1960s. But why has Postminimalism again become au courant after losing favor with succeeding artists in the 1980s and 1990s? Not that Postminimalism ever became invisible for new generations as completely as did Abstract Expressionism and Formalism. But why have these latter movements become irrelevant while Postminimalism and Conceptualism have not?

The answer seems to lie in how current generations of artists and viewers are learning that the earlier generations were not always what they represented themselves to be. The First Modernist Century of Art was not -- as so many today believe -- an epoch that exhausted what can be discovered and invented in the name of any one of its movements: Impressionism, Expressionism, Cubism, Symbolism, Dada, Surrealism, Action Painting, Fluxus, Pop Art, Minimalism, Performance Art. There is no debate that each of these movements came to an end despite that each lives ubiquitously on in the studios of artists. What we never truly note in our art histories is that these various movements didn't end because the terrains and concerns that each movement introduced were exhausted. They ended because amid the fever of discovering and mining the radically new in a century that prized the avant-garde, the rapid pace of the convulsive changes transpiring throughout international modernism and the invention of successive movements ensured the founding members of those movements were accorded the most vaunted accolades for pushing the avant-garde ever forward toward the new, uncharted, provocative and transgressive.

It didn't matter that no art movement truly exhausted the parameters of the paradigms they introduced. (Can an idea truly become exhausted? More likely it is we who tire of it.) Nor did it register among the ideologically transgressive that the popular culture often assimilated the most accessible or the most notorious contributions of a movement in watered-down imitations. What mattered was that the race to the next new invention or innovation accelerated as required to assure that the myth of progress and the canonical apotheosis of the great innovators of profoundly new ways of perceiving and shaping form, action and ideas could be sustained by its own transitions into the next phase of invention and innovation regardless of however it contradicted or challenged -- in fact because it contradicted and challenged -- the paradigm of art preceding it.

That is until the 1960s. This is when the art academies first came to assimilate Modernism and its critical and theoretical apparati, and by the 1980s academics turned their scrutiny on modern artists to ensure that the avant-garde would endure. We know, however that it did not endure, at least not as a succession of formal innovations approved by academics. The avant-garde evolved into a series of cultural activisms that sought parity for marginalized cultural identities and histories while dismantling at least many of the barriers based on false essentialist ethnic and gender identities. In tandem with these activisms, formal innovations became secondary. By the 1980s the avant-garde progression of formal principles and practices came to a halt, so that in the last two decades of the 20th Century nothing in the market place of Modernist art could be championed without it first being submitted to a political-academic critical inspection. At once the accelerating pace of Modernist invention and innovation decelerated. In its place was germinated a zeitgeist of ironic engagement of an academic nature that came to supplant the spontaneity of the avant-garde with a self-reflexivity that slowed innovation to a crawl. The academics, artists, critics and curators, replaced the avant-garde with the myth of Postmodernity that became a kind of twelve-step program for creatives addicted to but unable to inaugurate significant invention or innovation largely because they converted to the self-fulfilling prophecy that the new had been exhausted.

Whatever we think of this encapsulated narrative, the last truly original and concurrent movements of Modernism are Postminimalism and Conceptualism. In fact, it is because both of these movements, whose boundaries are so porous that artists engage effortlessly in both simultaneously, are arguably the most open-ended of all art movements in terms of their employable processes, while being inclusive of nearly all media and material, sensory and structural innovations.

The blending of Postminimalism and Conceptualism isn't only being seen in retrospect or as a route to reappraising protean artists who had been passed over in their lifetimes in the race to proceed to the next newest art movement. A new generation of artists who had been schooled in the history of art no longer believe in movements. Given the evidence of their art and expressed concerns, two such artists are Ruth Hardinger and Kara Rooney. Neither comments explicitly on either Postminimalism or Conceptualism as a personal practice, but their art and comments implicitly align with the concerns and practices of Postminimalism, particularly their shaping of objects by hand, their concern for materials and textures, and their use of a gallery space as a field in which single works interact to form a greater gestalt. Conceptualist cultural concerns, meanwhile, motivate them as well as inform how they shape, light and intersect their objects with other objects in the field to elicit ecological, architectural and bureaucratic social contexts for Hardinger, and the universal unification of structural-linguistics, morphology and semiotic signifiers for Rooney. It is in particular the new global agora for art that has expanded and intensified the political and cultural functions of Postminimalism and Conceptualism for both these artists.

Both the reclamation of artists neglected in the past and the reclamation of the disparate material and conceptual concerns of that same earlier generation by artists today evidence that the artists who became renowned for their introduction of Postminimalism and Conceptualism came nowhere near to exhausting the potentiality of meaningful innovations afforded them. In retrospect, we can incline ourselves to considering not only that all four artists here discussed, despite being separated by generations and cultural barriers, share being informed by the global confluence that Postminimalist and Conceptualist tendencies afford artists. While the generation of Gego and Mohamedi initiated and sustained some aspects of the Postminimalism that survives today, Hardinger and Rooney salvage them as a matter of disinterest of artists today in forming movements.

Unlike the artists today who have had ample exposure to generations of artists who liberated sculpture from strict formal principles, Gego and Mohamedi had to contend with the constrictions of formalist ideologues. Feminism and other liberation activism had not yet mitigated the reception of women within art in Venezuala and India as it had begun doing for their New York contemporaries, Eva Hesse, Lynda Benglis and Nancy Graves, or even as psychological liberation propelled Lygia Clark, which may account for why their greatest innovations come not until their late work. And yet Gego and Mohamedi managed to transgress the formalist restrictions of their predecessors without a milieu like that formed by the Postminimalists in New York, a move that made each legendary in her country for the singularity she fostered. Only upon showing her suspended Chorros sculptures in Betty Parson's New York gallery (and which were reinstalled in the Dominique Levy Gallery in the fall of 2015) did the pliable and transposable features of Gego's trademark wire membrane become identifiable with the New York artists who had elaborated similarly interchangeable and transient installations under the name Postminimalism.

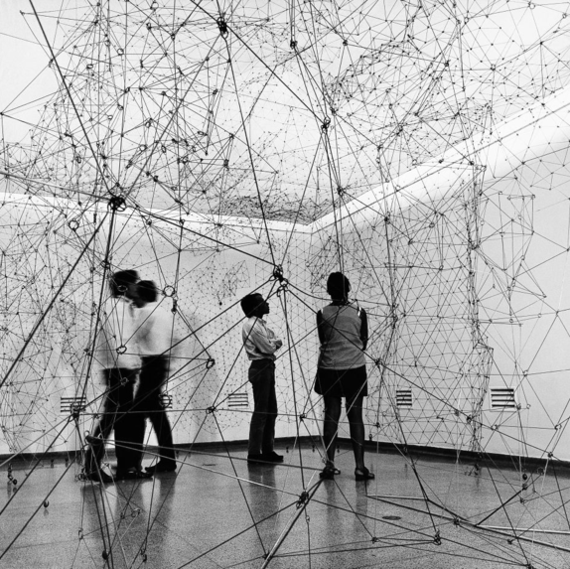

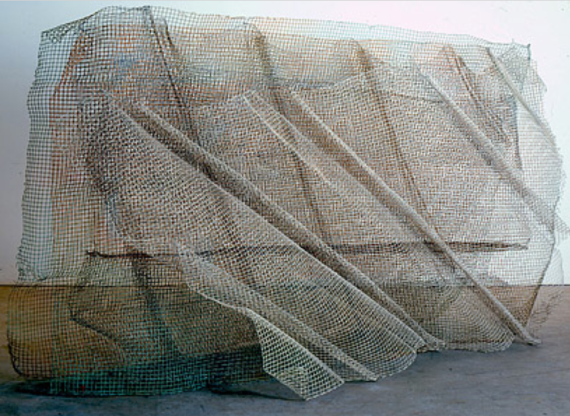

Gego's now renown Reticuláreas, first made in 1969, consisted of a series of wire sculpture installed from wall to wall, ceiling and floor that cast shadows creating an illusory effect of multimedia drawing in three-dimensional space, trading off between the line of the wire and the shadows of the wire cast on the confines of the gallery. The date is significant because the Reticuláreas predate the illusory small scale sculptures that Richard Tuttle made in the early 1970s and exhibited at The Whitney Museum in 1975. (See the image of Tuttle's wire, graphite and shadow drawings in this post.) In that groundbreaking exhibition, Tuttle worked with only one or two small wires anchored at two end points to compose his compact wire drawings, but then he conjoined the points at which the wires adhere to the wall with arching pencil lines drawn onto the wall (and around a corner if one was present), then finished by lighting the small sculptures so that the shadows cast by the arching wires formed a third drawing. The three modes of drawing were at times so uniform that it took careful viewing to determine which line was wire, graphite or shadow. Whether Tuttle saw Gego's work at Parson's or anywhere else, we only know that Gego and Tuttle are the first to claim that wire and shadow can be constituted as drawing.

Unfortunately, Gego's work was shown too infrequently outside Venzuela. Besides her show at Betty Parsons, Gego was featured in shows at Hunter College, The Drawing Center and El Museo del Barrio, with the most significant being the 1965 group exhibition, The Responsive Eye, at MOMA. She was rarely if ever properly acknowledged as the Postminimalist she was, at least not in direct relation to the New York school.

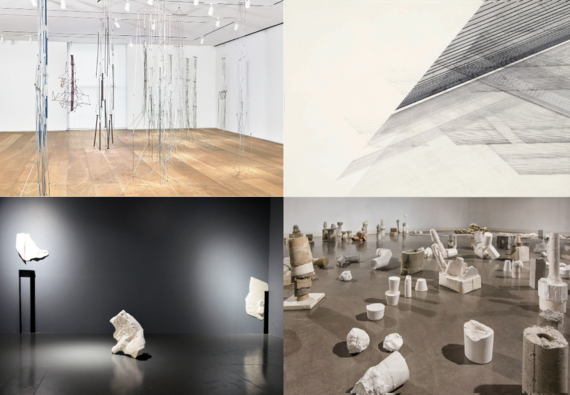

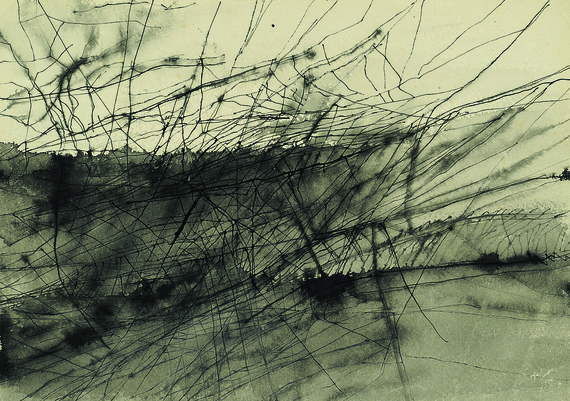

Gego's Chorros sculptures, shown last fall at Dominque Levy New York, count among the first suspended wire sculptures to be discussed as drawings in space. These forty-five years later, as we treat abstraction less reverently and metaphor again is attached to suggestive form, the Chorros appear as waterfalls, enough for this viewer to imagine a sublime pairing with the poured paintings made by Pat Steir in the 1990s and 2000s, an artist who is also very much a postminimalist for embracing allusions to materialist and gestural metaphors over the illusion of realism and the elusive tropes of painting. Londoners will be treated by the Levy gallery to one of Gego's magnificent Reticuláreas, an immersive web or membranes assertively occupying the gallery in ways rivaling the transient and pliable installations of Eva Hesse, yet keeping within a narrower range of site-specific parameters that conform to the space at the same time the webbing takes the space hostage. Gego's are exceedingly irregular intersections that take Postminimalism further than Alan Sarat. For Sarat, industrially-manufactured mesh and fencing articulate intricate relations between positive and negative spaces at regulated intervals. By twisting and bending the mesh, Sarat desecrated the sacred Minimalist grid with as much relish as can be imagined in the austere artworld of the 1960s and 1970s. In this, Sarat is also the Postminimalist who shares most with Mohamedi's drawings, despite their being the more unpredictable. In fact several of Mohamadi's drawing from the 1970s appear as if the two artists composed a dialogue of negative and positive spaces outlined as much by taut lines as by the loose and overlapping ones. For that matter, Sarat, Gego and Mohamedi all show great and loving attention to the nexus of intersections, the source of strength and endurance imparting flexibility in sculpture, and perspectival variety in drawing and painting.

The Levy Gallery notes that Gego utilized both stable and unstable materials, the latter making her work companions in concept to Barry La Va's fields of scattered sculptural remnants. The stable elements of art is the sculptural installation itself (which remained in place throughout the duration of a show), while the unstable elements consist of the constantly changing shadows and the slight movement in Gego's designs due to the fragility of her materials, and emphatically in the mutability, transience and variation of the spatial installations that never appeared the same. In the late 1960s and throughout the 1970s the mutability and high degree of specificity demanded of each installation by the artist required that the artist (or an instructed surrogate) be present to direct each installation. That this demand was met by many art institutions was sometimes jokingly-yet-seriously referred to by the Postminimalists as the artist's 'power'. Gego was one of those artists who commanded such 'power' sensibly. But the jokes shared among the New York Postminimalist was that the Minimalists wielded an autocratic power in having their demands met to install towering gestalt metal sculptures, some two or more stories high, situated in the company of corporate skyscrapers, or in competition with the sprawling landscape, at the unprecedented expense of tens of millions of dollars spent for labor, fabrication, transport, and storage.

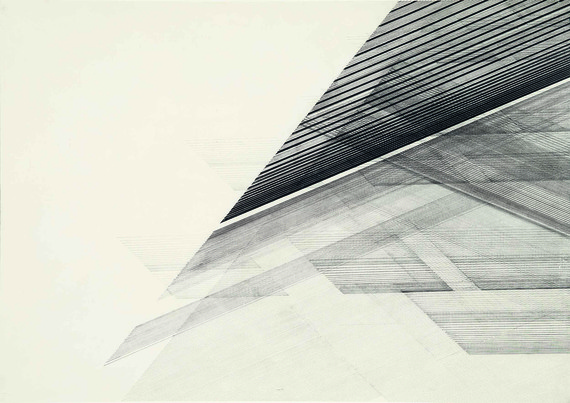

Of course a brilliant Minimalist such as Agnes Martin never sought to wield such power and her work today commands the attention of every Modernist collection in the world. Mohamadi is often compared to Martin, though I believe that comparison is superficial. Martin's work is nearly always a gestalt that can be summoned to mind visually even if only approximately as a simple grid with repetitive shadings, dots, etc. By contrast, Mohamedi's work is altogether too complex and varied within the comparison itself to be summoned to mind like a gestalt. This is one difference between Minimalism and Postminimalism. The degree to which our power of recall is strengthened by our understanding of basic geometric shapes and perspectives. The test of whether Mohamedi is a Minimalist or a Postminimalist is to be found in the manner in which she elaborated complex compositions that are anything but gestalt images -- that is the simple compositions or images that the mind can recreate without difficulty as say, a pyramid, a cube, a sphere can be summoned to mind, or some simple elaboration proceeding from combining simple volumes or planar shapes. Even in her most exacting, perfect drafts, Mohamedi's later works impart a sense that only the critic Barabara Rose put into words in her October 1965 Art In America essay, "ABC Art"," that the Minimalists were a generation that raised questions which were ultimately unanswerable, questions that were thought by many to be formal, yet which were underpinned by sociological conditions and ideological choices. This is closely associated with the fact that questions of content or meaning were made more prominent by Minimalism's omission of them."

To answer the question, "Is Mohamedi a Minimalist or Postminimalist?", the answer is neither, only because she was a 'postminimalist' before there was a minimalism to be post to, making her a kind of preminimalist without the closures. More sensible is the question, is Mohamedi an agent of stasis, centering and stability in creating fixed, gestalt geometries? Or is she an agent of dynamism, de-centering and destabilization in opening geometric spaces to the unseen and unforeseeable? I advocate the latter, even if she has written early on about the purity that the Minimalists obsessed over. Getting back to the comparison of Mohamedi with Agnes Martin, it is a difference comparable to the period of Mannerism that followed the Classicism of the Renaissance, with Martin the Classicist and Mohamedi the Mannerist. The quest for purity and perfection, which account for Minimalism's paring down to bare, necessary shape and volume, is often a psychological response to disorder of great magnitude. If for Gego the memory of Germany after Kristalnacht and her escape in the treacherously late year of 1938 kept the specter of destabilization central to Gego's work alive and made it likely impossible for her to become a minimalist. Mohamedi too may have had the memory of the violent partition of Pakistan and India calling her to account for her emphatically-decentered, asymmetrical compositions (as opposed to Martin's symmetry), and especially her steep inclines and multiple perspective points that at times evoke the cul-de-sacs where things go down without our knowing.

But we must remember that Mohamedi had the solace of the religious aniconic aesthetics of the mosque drawing her serenity out from her and onto the page. Edward Said would have non-Muslims acquaint ourselves with more than the mathematical patterns and the incomparable harmony of the mosque designs. We should as well enlighten ourselves with what really goes on, he wrote, inside the mosque for the majority of Muslims: prayer; contemplation; centering; a few moments of tranquility; being human before an image of God. But Said never takes the Muslim to task for making the same generalizations because they know the deeply contemplative aspects of Islamic geometry. Mohamedi traveled to the great mosques of the Middle East and the experience we are told had a defining influence on her vision. And yet she does not indulge the interlacing of arabesques that characterize Islamic design. Instead she plots out the intersections of acute, obtuse and right angles in a fashion recalling Renaissance perspective and Modernist architecture, especially the architecture of the skyscraper. It is an intriguing contradiction, yet it is evident that it is the schemes of angular architecture that disallows her imagery from dissolving into anything close to disorder. Mohamedi consciously or unconsciously delays our arrival at the purity that she herself claims to have sought. Much has been made recently of her diary entry from 1960 in which Mohamedi states her conscious ethos: "It is a most important time in my life. The new image for pure rationalism! Pure intellect, which has to be separated from emotion, which I just begin to see now; a state beyond pain and pleasure! Again a difficult task begins."

The production that Mohamedi issued after her sojourn among Asia's greatest mosques in the 1960s, as we see above, is not pure abstraction, not rational to the extent it would become by the 1970s. Of course at the time the drawing would be lumped together with Expressionism. But Expressionism is erratic, anti-logical, desirably rough and off-putting, symptomatic of irrepressible anxiety, compulsive drives. By contrast the drawing here is elegant, schematic, logical insofar as its parts are not in conflict, and every inch is meticulously rendered: all qualities of Postminimalist abstraction, not Abstract Expressionism. The image is not truly expressionistic; it is marked by a remarkably-controlled draftsmanship, the kind that would be poured into her later mannerist abstractions. The dilemma is instructive: we must soon call 'Postminimalism' something new and more accurate: it requires an appellate that does not construe a presumed chronology, is not post- or pre-, that is just resolute about asserting itself emptying of meaning in the Zen fashion that fascinated her, as it had Vasudeo S. Gaitonde, whom she greatly admired.

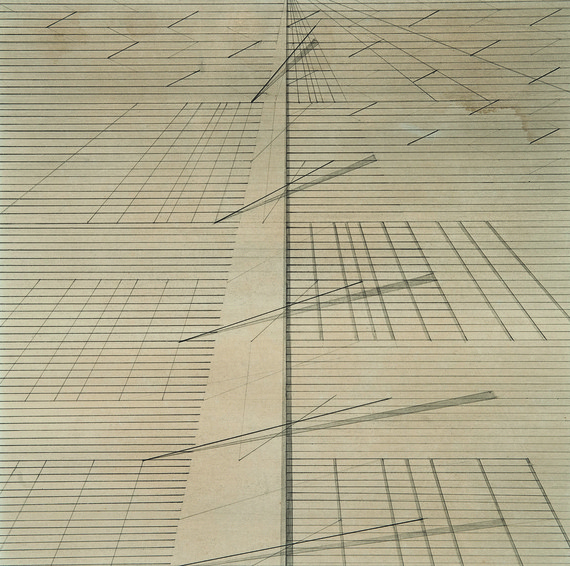

Instead of abandoning Expressionism or Minimalism, Mohamadi conflates the two in a fashion that Agnes Martin would never have countenanced. Which is why it is incorrect to say that Mohamedi is the Indian Agnes Martin, despite that she and Martin were in 2007 paired at the 2007 documenta in Kassel, Germany. While it's true that Mohamadi kept to an obsessional programatic scheme, as did Martin, it was a scheme that remained open to breaking off abruptly and arbitrarily, and most importantly without obedience to an imposed logic, such as that which Martin imposed upon herself. While Mohamedi's more minimal (in contrast to Minimalist) compositions allow her to chart inclines that form one atop another, the drawings of the 1970s do not close the compositions off to dispersals and minute shifts in direction that are not rationally perspectival. That is, they don't have a common generative point of progression, in contrast to Martin's grids, but rather allow momentary excursions that are idiosyncratic, however subtlety and unobtrusive. This interplay of reason and caprice is distinctly Postminimalist, as the dating of these works as post-1970 affirms. Even in the drawings that keep to one or two common perspective points, Mohamaedi weaves a complexly-layered lattice of varied intervals, the thickest of which blacken out in ink or graphite geometries with no apparent reasoned perspective underpinning the scheme that challenges Minimalist gestalt principles.

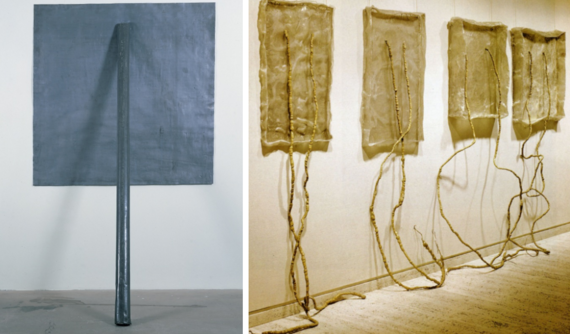

Of course sculpture is the true medium of Postminimalism. Which is why the FiveMyles exhibition and its offshoots by the artists Ruth Hardinger and Kara Rooney is so compelling. We should remember when defining Postminimalism that it was a movement of artists who proclaimed painting to be either dead or to be in reality another form of sculpture. Objects as much as images. This is one reason why color played a role in the making or finding of Postminimalist sculpture.

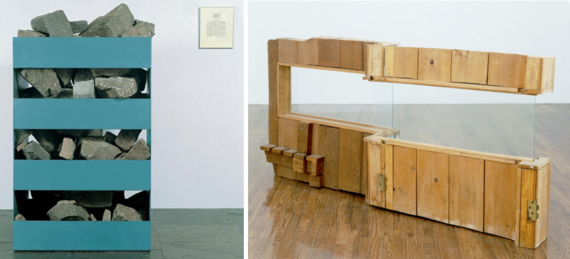

The most salient feature of Ruth Hardinger's work is her field of objects. Each has been somehow formed and crafted with a kind of mythopoetic attachment of fictional function: a totem, an envoy, an archeology, an ecological marker. But these are their fictions, as Hardinger fashions all her objects herself. None are found, none are truly archeological, as are Gordon Matta-Clark's. They are constructed, mostly from cardboard and concrete, which compels her to claim that this is so she will be ever mindful of the reality of weight. In this she shames the Minimalist, who seemed throughout the 1960s and 1970s to think that the bigger and heavier the sculpture, the more immutable, permanent and historical it would be.

In her economical catalogue for Five Myles Gallery, Charlotta Kotik conveys that a central tenet of conjoining the work of Ruth Hardinger and Kara Rooney in her show Trace Matter was because their work reflects diverse issues and realities. She writes that the pairing of the artists displayed to what extent they were "intersecting in key areas such as the frequent acknowledgment of cultural history; in the physical traces rendered by the intensely physical effort used to create a majority of the pieces; in the complexity of conceptual approaches; and in the work's partially revealed narratives. While utilizing a plethora of techniques and materials, both artists choose to express themselves primarily through the exploration of three dimensional or sculptural idioms, with drawing, photography and digital collage all serving to convey a multiplicity of ideas."

Then Kotik got down to the business of what those idioms are.

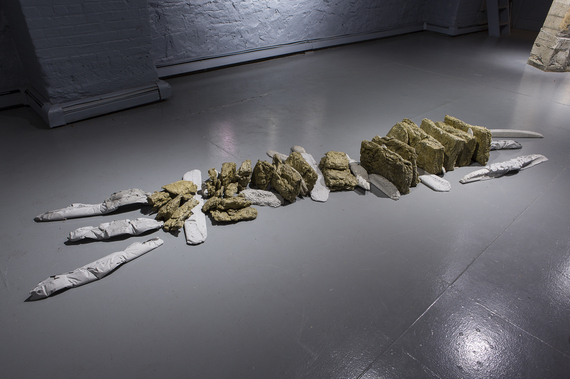

"In Conundrum / Consideration, 2015, Hardinger recalls linear shapes of ancient African stone objects from Tenere dating to about 8,000 years ago, believed to serve as food utensils. While transforming their forms into segments of her piece, she distorts the original shapes through the subjective processes of her memory into entities hovering within the past and present. She pairs them with the rectangular shapes fashioned from a contemporary architectural material, stone wool, an energy-efficient insulation, creating a complicated dialogue of incongruous materials and distant time periods. ...The memory of ancient monuments or totems is manifest in Hardinger's Envoy # 30. Compact, with a wide variety of surface treatments and materials employed ... this simplified and enigmatic shape is cast as a messenger to warn us about the ecological concerns that are destroying civilization as we know it. Growing from the deep concerns for the environment and its steady destruction, it is the artist herself who sends us messages through her work. These are encoded not only in her sculptures but also in the mysterious content of her Envelopes/Envelops, 2005-15, where the low relief, the implied fragility and the use of graphite, a pure carbon, brings to mind the fragility and vitality of earth layers ant the organic life's compounded interactions."

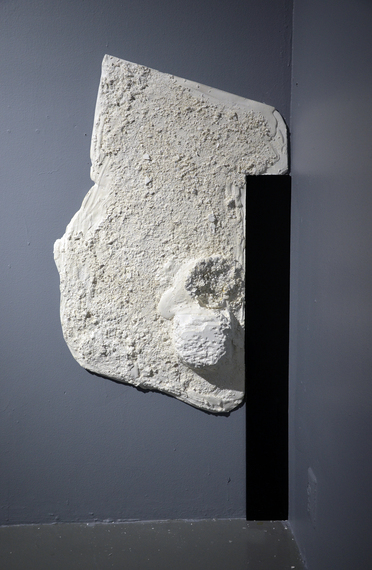

"Kara Rooney's series of Alters manifests her interest in the issues of personal and collective memory, history, philosophy, and linguistics, collapsing them into tightly integrated three-dimensional entities. ... Elements in the wall bound Alter no. 1, 2015, situated at eye level ... its straight planed construction functioning as a minimal sculpture in and of itself that could be also seen as supporting the sculptural Hydrocal segment that hovers closely above, is highly reminiscent of exquisite forms of classical Greek sculpture. Rooney's interest in classical antiquity and the mediating filter of history is further exemplified in the carefully folded pleats of two chiffon scrims that bring to mind the fluting of Greek columns. Although transparent and almost immaterial, the scrims possess a firm architectural presence -- their silkscreens printed photo images, which reference multiple natural and manmade forces, can certainly be read as an illusion to this fact."

As her statements make clear, Kotik has taken pains to make the artists au courant. But their contributions are also significant for building on the foundations of an earlier generation of artists. Hardinger, for instance, inherits the concerns of two artists who died too young in appropriating architectural materials taken from deconstruction sites. As already mentioned, Hardinger recalls Gordon Matta-Clark (see image), whose dialectal explorations of constructed spaces culminated in their deconstruction by cutting whole buildings into cross-sections that enable the public to view the insides of formerly enclosed buildings, exposing multiple perspectives inconceivable to earlier generations of architects and artists. Hardinger doesn't accumulate actual architectural remains. She simulates them, but the simulation references the art history simultaneously with imparting a concern for the toxicity revealed to be of concern in modern housing. At the same time, Hardinger invokes Robert Smithson's dialectal essays concerning the conceptual and material exchange and cross-fertilization of indoors and outdoors, what he called sites and nonsites, by bringing into the gallery excerpts of nature while making the environmental surroundings outdoors a gallery without walls. In this Hardinger works much like the Paleolithic or Neolithic artist who re-presents the world surrounding her in artifacts brought into the temple or home. Yet as a contemporary artist, she does so while defining the gallery space not merely as a locale for situating discrete works, but like Barry La Va and Eva Hesse, she makes the galley a field of objects related in formal sensibility, urban archeology and political/ecological implication.

To expand on Kotik's foundations. Ruth Hardinger derives her lessons in abstraction largely from the world and its environmental and political relations, while Kara Rooney is more reflective in terms of the phenomenological tradition of dismantling assumed "concrete" realities to distinguish and enlarge our consciousness of the hidden and neglected features that we empirically observe yet for cultural and linguistic reasons get unconsciously fused with larger observations that we construct together as objects in the world without knowing much about those objects' parts. Art historically, though perhaps unintentionally, both take up the mantles of earlier visionaries of the Post-minimalist and Conceptual era introduced in the late 1960s.

When I asked Hardinger to write a statement for this commentary, she offered the following.

"I'd heard that stone wool (aka rock wool) is one of the materials used to insulate walls of passive houses, reducing emissions in these home by 80 to 90 percent. In response to this knowledge, I used stone wool insulation for Conundrum / Consideration. This sculpture sprawled on the floor like an animal from the Cambrian period, reminiscent of an animal which geologically was converted into a fossil, and then again converted - this time by man -- to a fossil fuel. The stone wool insulation provided an opportunity to say during the panel associated with the exhibition, that we need to tackle climate change, and that passive house construction is one of the many ways to do so. Interestingly, despite its conceptual inspiration, my sculpture, Conundrum / Consideration, continued to express abstraction even within the matter of rock-like formations."

"I like materials that come from basic origins and have teeth with sources and definitions. Most of these favored materials include powdered graphite, milk, concrete, cardboard and stone wool. Because the procedures I use encase concrete in a cardboard box or the graphite covered with milk, I don't see a final stage of the work until it dries or cures into the resultant forms they become. I don't modify these formations then. These procedures give a sense (or spirit) of being in collaboration with the materials. Ultimately, graphite, rock, concrete and other materials have a living life whose vitality draws my interest, even though their time frame and elements are millions of years longer than those of humans."

"Envelope/Envelop. Graphite, the largest material in this work, is a pure carbon, and pure carbon is an element required for all life. That's a back-story for these pairs of works on papers. However, they are about much more than their material. Experiencing an inner protected place, embraced by something that envelops, is one way to see these works on paper. Mounted on the expanded brick wall in the gallery, these graphite works on paper are paired-up on one side and again on the other side. The pair on one side has an open channel and on the other side the pair adjoins. Spacing of the Envelope/Envelops pairs reach across the wall as though in a conversation ... or an action arising between them, with open and closed pathways. The surfaces of these graphite positions are open to determine a scale concept or space distance and depth. These pieces were total surprises when they dried."

"The Envoy #30 / Standing is a solid, heavy, strong, tall messenger of abstraction that has four sides from the concrete cast inside the boxes. The concept of messenger reaches across time and cultures, associating to totemic constructions and power. The front and back sides each contain an inside smooth plate of concrete embedded deeper into the surface, as though a window-like form was placed there to entice or envision the vitality of the inside. The cracks running up and down its sides (another surprise in its creation) make its formation appear to have been actively made, and actively viewed."

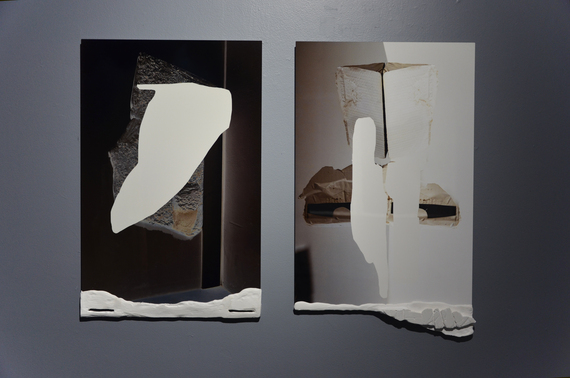

Rooney on the other hand revives an analytical mode of presenting art that doubles as a formative language analysis, the kind introduced to the art world in the late 1960s by conceptual artist Joseph Kosuth. She starts out with the kind of standard phenomenological art making that redefines such traditional artistic values as color, line, mass, texture and shading as perceptually relativistic values. Then she subjects them to multi-layered, illusionistic manipulation that results in multiple conceptual readings based on a similarity of appearance. We may think we are looking only at an abstract hydrocal abstract, but upon close analysis we find embedded within it a small, slightly hidden photograph or silkscreened image. Upon discovery, the sculpture becomes a collage, and the language we use to describe it must change. Similarly, Rooney's photographs are conjoined with collage then rephotographed to create a single image that reads as a textured collage. The interplays of translucency and opaqueness are no more than illusionistic conveyances of a flat modulation of tonal values on a smooth surface. In evoking the processes of Conceptualism (Kosuth), Postminimalism (Tuttle), and Surrealism (Man Ray), Rooney brings together materials and epochs not ordinarily thought of as compatible but which discretely together inform the art history we inherit.

Rooney, who is also an art critic with The Brooklyn Rail, doesn't stop at this rudimentary level of form-and-meaning conjunction. In an interview with Sara Jimenez for Artfile Magazine, she elaborates further.

"There's something about the transcriptive act that has always intrigued me- how the written form can crystallize thought, can embody a sense of time or place, in a very different sphere than the object can. My visual work stems in part from an interest in seeing if I could change my relationship to the object by working through the ideas of coding that are attributed to the letterform or to written script, between the tangible world of text and the ephemeral nature of memory."

"The separation between object and text or object and theoretical thought is a slippery distinction. One can't exist without the other. We need the image just as much as we need the textual component in order to make sense of our surroundings. They're kind of all we have as a way of moving towards understanding or meaning. As someone who traffics in both mediums, I'm hyper aware of this tension or dialogical play."

"The sculptural works I create are intended to act as visual semaphores, or stand-ins for speech. I'm enlisting the semaphoric act of cueing as a means of widening the gap between speech, visuality, and definitive conclusion. The object acts as an entry point for understanding that there is something else that exists beyond the 'thingness' of the object. What that is for most viewers is a sense of the theoretical or the textural, not necessarily more materiality. Something that is less tangible, less easily pinned down. This is a lot to ask of abstraction but I'm doing it anyway!"

We have been at this level of meaning formation in art before, but not in the materially visceral and tactile way Rooney conjoins it with the different textures, materials, colors and illusions. It was articulated for conceptual art in 1968 by Joseph Kosuth in "Art After Philosophy". "Colors and shapes are the art's 'language'." "Modern' art and the work before seemed connected by virtue of their morphology. ... art's 'language' remained the same, but it was saying new things." "Artists question the nature of art by presenting new propositions as to art's nature. And to do this one cannot concern oneself with the handed-down "language" of traditional art, as this activity is based on the assumption that there is only one way of framing art propositions. But the very stuff of art is indeed greatly related to "creating" new propositions." "A work of art is a kind of proposition presented within the context of art as a comment on art. We can analyze the types of "propositions. ...Works of art are analytic propositions. That is, if viewed within their context - as art - they provide no information whatsoever about any matter of fact. A work of art is a tautology in that it is a presentation of the artist's intention, that is, he is saying that that particular work of art is art, which means, is a definition of art."

Pinning down the thingness in Rooney's semaphores requires going outside the system she has constructed for herself. Since she introduces language as an analogy to how her work functions we are free to project onto her work two models from structural linguistics to show how her work does become meaningful despite its being abstract. In fact we may appropriate two models for language formation at the root by which meaning becomes attached to abstract constituents. We begin with the phoneme, what linguists call the a basic unit of a language's phonology, the system of sounds and the written letters that signify those sounds. Take the term 'remaking". It has three phonemes 're', 'make', and 'ing'. The phoneme does not refer to meaning. The phoneme is abstract, the way that Rooney's white hydrocal and black resin objects are abstract. Meaning is only attached at the level of morphology with the morpheme, the smallest grammatical unit in a language. Although the word 'remaking' has three phonemes, it has only two morphemes that ascribe meaning to the single phoneme: 're' and the double phoneme 'making', to assemble the meaning 'making again'. In fact we may debate whether 'making again' is one or two morphemes, but that is the province of perceptual theory in which the question "Does 'making' always imply 'making again' in the phoneme 'ing', that imparts the meaning 'a stream of making?').

But while Rooney's work always functions as a visual phoneme or visual conjunction of phonemes, it only functions as a morpheme or conjunction of morphemes when the viewer sees in the work meanings that Rooney may or may not have intended, and unless she has told us, we are guessing at. But guessing at meaning is the most primitive level of meaning formation and there is no authority in the world, not even the artist or the authorial culture that designates preferred usage, that can tell us what meanings to ascribe to abstract forms, whether those forms are phonemes or abstract sculptures. But in this the only difference between abstract forms and pictorial forms is that we share the meanings that are ascribed to the component signifiers of pictures.

Despite the various layers of art history invoked by Hardinger and Rooney, the dominant aesthetic apparent in their work is that of the 1970s generation, whose sense of the social contextualization of art in place of the formal and psychological exercises that the Minimalists and other formalists exalted, dominates the gallery context. But we must distinguish the materials that Hardinger and Rooney employ, as they are considerably different from those the Postminimalists favored, as are the conceptual concerns and the contexts of their inquiries. Even Rooney's affinity for illusion is more complexly defined and rendered than those offered by Man Ray and Tuttle, just as her material manipulations are more nuanced than Hesse's. Hardinger's ecological and health concerns are also more chronic to society, given that our knowledge of the materials composite to modern dwellings has been increased exponentially.

What remains the same, however, is that both artists carry on the open-ended ideology of the Postminimalists and the Conceptuaists, in terms of the diverse technologies and materials, the reflection on past and present experiences; the forces, traditions and languages that inform current and future generations of artists. In so doing, artists such as Hardinger and Rooney disprove the thesis, as it was argued at the end of the 20th Century, that the Modernists had exhausted all the possible innovations of their movements, possibly exhausted the formal, conceptual and contextual potentialities of art altogether. The truth is there is much terrain and and many more open-ended material, conceptual and performative systems of artistic production untouched by the artists and movements of the last century and that present themselves to artists of today in what now can be seen as the interstices between the schools and movements bestowed to us by 20th-century artists.

Listen to G. Roger Denson interviewed by Brainard Carey on Yale University Radio.