Unlike most photographers, Khaled Zaki must glide his way deep into the sea to shoot portraits of fascinating faces and admirable bodies. Armed to the teeth, quite literally, Zaki, in water, chases his reluctant subjects that are a lot fussier than the biggest supermodels on land.

With around 25 years of diving experience behind him and nearly as many years photographing and filming an ecosystem we know little about, Zaki is an underwater globetrotter.

“On each dive I dive, I shoot around 200 pictures. I delete 170, retain 30. Of these, I might get a couple of good ones,” the 40-something Egyptian expat, who frequently travels across the world in search of aquatic superstars, tells Community, “It might take me around 15 minutes to complete that one round of pictures. I move very slowly and I move with the fishes, while factoring in the angle of the sunlight and choosing the right lens for the right shot.”

All the passion and hard work has paid off. The Master Instructor with Professional Association of Diving Instructors (PADI) won the first prize in the recent 4thUnderwater Photo Marathon, under the DSLR Ambient With or Without Model category. The prestigious competition featured 380 competitors from 37 countries and Zaki, Qatar’s lone entry, brought home the big prize. “There were huge stalwarts in the competition. I got lucky with this nice shot I got,” he says, referring to his award-winning frame.

While floating about in Thailand’s picturesque waters, earlier this year, Zaki spotted a Grouper fish and followed it to the depths. “I slowly trailed it and set up my camera. Eventually, I caught it eating a Jackfish,” he says, pointing to the picture on his laptop brimming with photos and videos, “I was thrilled.”

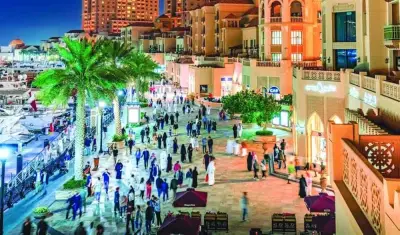

An ardent marine enthusiast, Zaki has been living in Qatar for 16 years, teaching diving for more than two decades and also working as a marine consultant for underwater photography and videography. “When you build something like The Pearl Qatar or Lusail, you need to discover what’s at the bottom. In 2004, I filmed at those locations to take samples of almost every centimetre underneath,” he says, “Likewise, I have worked on projects at Messaied, Al-Wakrah beach and Sealine Beach, apart from filming for pearl diving ventures and studies related to turtles. I have also worked on several marine documentary films with BBC network, Qatar TV, and AJ+ among others.”

Zaki believes an extensive knowledge of marine life is a pre-requisite to successful underwater photography. “That’s how you can predict the behaviour of each of the fishes. When I dive, I need to know the season of the fishes, their location, and what species can I expect to shoot. If I am exploring sandy bottom, for instance, then I will encounter more of sandy bottom creatures such as snails, manta rays and crabs,” Zaki says, pointing to his stunning close-up shot of a Sting Ray, “They are all very peaceful as long as you don’t disturb them.”

Suited up in his snorkel, goggles, flippers and MKVI rebreather, Zaki routinely sets off on his photography excursions with a fully-loaded Canon 5D Mark-III, couched in a high-end Nauticam housing to protect it, and a couple of big bright lights that he plays around with.

Obviously, good light under water is as critical as it is on land to create a most compelling image. While Zaki prefers optimising ambient light as much as possible, he uses his lights to illuminate his subject such that the details are masterfully highlighted as if they are shot in a deep sea studio.

“The deeper you go, the more light and colours you lose,” Zaki explains, “It’s not just that the light must be cast on the subject, but that the light must bounce back and return to my lens so that I’m able to capture it in the frame. So I keep experimenting by putting the lights at the back or the side of the subject, until I achieve the desired effect. All this comes after I adjust the white balance of my camera according to the amount of sunlight pouring in.”

While teaching, Zaki always advises his students to be calm, comfortable and relaxed under water. Often, underwater photography requires us to move so slowly that we may film only a few dozen cms in 20 minutes. “Good buoyancy control is crucial so that you don’t disturb the marine life which is rather shy,” he says, “When you spot an interesting sea creature, the key is to behave as if you are not impressed. Pretend like you didn’t see it but keep an eye on it. Allow it to develop the curiosity to come close to you. If you even breathe excitedly or move an inch suddenly, the fish will disappear in a flash.”

With measured movements in gentle increments, Zaki allows his subject to become as much at ease as he is. “The shape of the creature you are expecting will grab your eye. And suddenly, you might have a dolphin passing you by. So you need to be quick yet very cautious with your moves to capture the finest that the wonderful underwater world has to offer,” says Zaki, who usually shoots under water for about two hours.

Though Zaki can go 120 metres below, Qatar’s waters are shallow, limiting his journey to 50 or 60 metres below. “Qatar has amazing marine life and diving in North Qatar and the inland sea will surprise you with the wonders you will discover.”

Apart from describing how safe and serene the water world is and persuading both the curious and the apprehensive to try diving, Zaki likes to talk a lot about corals and our need to protect them.

“Some estimates put the total diversity of life found in, on, and around all coral reefs at up to 2 million species. Coral reefs are home to 25 per cent of all marine life, and form the nurseries for about a quarter of the ocean’s fishes, including commercially important species that could end up on your dinner plate any night of the week,” Zaki explains, “Coral reefs have survived tens of thousands of years of natural change, but many of them may not be able to survive the havoc wrought by mankind.”

With roughly a quarter of coral reefs worldwide already considered damaged beyond repair, and with another two-thirds under serious threat, Zaki’s frustration with people’s lack of awareness about these nature’s angels is understandable. “More than 80 per cent of the world’s shallow reefs are severely over-fished. If we don’t act now, 60 per cent of the world’s coral reefs will be destroyed in the next 30 years,” Zaki explains.

The major threats for corals, Zaki says, are destructive fishing practices, overfishing, callous boat anchoring, pollution, and climate change. “It breaks my heart to see how the corals are being damaged here in Qatar,” Zaki says, “What I notice is that the Qatari government is spending a lot of time, money and effort to protect marine life, but something needs to be done with the people.”

The seasoned vet then offers an analogy: “It’s like your father is asking you to study for the exams and he is offering you every possible facility to help you score well, but if you are not fully convinced how important it is for you to study and get good marks, you won’t do it.”

Awareness, therefore, is key, feels Zaki. “The fishermen, for instance, aren’t aware of how vital corals are. If they have five or six boats, they drop the nets on or around the reefs, sometimes as many as 30 or 40, and when the time comes to pull the nets out, they will drop an anchor and yank out the nets that are stuck in corals, breaking huge amounts of corals in the process,” he laments, “In fact, a similar phenomenon occurs when people go for fishing, cruising, or diving — they use the GPS to locate where the corals are, drop an anchor there, then drag it through the corals, destroying a chunk as big as this room.”

The solution is simple, says Zaki. “We need to be aware of what our callousness is causing. We need to save corals and thereby save the underwater world,” he says.

READY, STEADY: Zaki, all suited up.