Eugene Robinson tells Panthers cautionary tale

SAN JOSE—Eugene Robinson stood in a sunlit room of this city’s convention center earlier this week, holding his hands far apart. From a distance he appeared to be recounting a football play, perhaps one of the 57 interceptions he made in a remarkable 16-year NFL career. Maybe he was deconstructing one of the Panthers 39 takeaways this season.

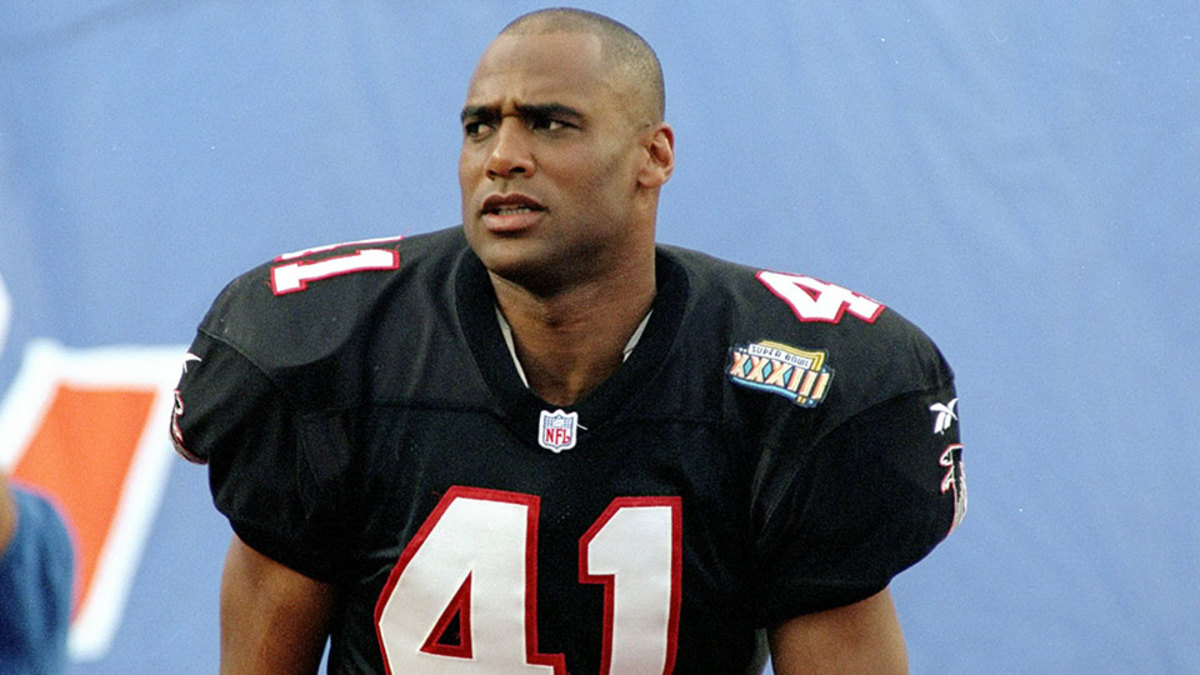

In fact, he was talking about a different kind of larceny. These days, the 52-year-old Robinson is thriving as an analyst for the Panthers radio network, and co-host of the morning TV show, Charlotte Today. Sixteen years ago, he was one of the veteran leaders of an Atlanta Falcons team facing the Broncos in Super Bowl XXXIII. On the eve of that game, Robinson was arrested in Miami for soliciting a prostitute. The ensuing media frenzy created a massive distraction for the Falcons, who were uncharacteristically out of sync – Robinson himself gave up an 80-yard touchdown pass – in their 34-19 loss to the Broncos. Always known as a team player, Robinson had robbed his teammates of their best chance to win.

Even with criticism, Goodell and the NFL keep winning to owners’ delight

Holding his hands far apart, he described the gulf between the model citizen he was when he woke up that morning – that day he accepted the Bart Starr Award, given annually to the NFL player "who best exemplifies outstanding character and leadership in the home, on the field and in the community" – and the disgraced john who was hit with a misdemeanor solicitation charge that night.

Robinson, deeply religious, was describing the distance that he had strayed from his Savior, talking about the moment “you realize that you’re way over here” – far removed from all that Bart Starr stuff – “and you say, ‘How the hell did I get over here?’ And all the world’s saying, ‘Hey who’s this dumb-ass, how did he get way over here?’”

He has spent the intervening years “walking back in this direction,” bringing his hands closer together as he spoke. The first and most important step, he says, was to apologize to his wife, Gia, who forgave him.

“My wife could’ve easily left me, and who would blame her?” he asks. Instead, they recently celebrated their 30th anniversary.

The most recent step toward redemption came last Sunday in Charlotte. Robinson had broached the subject with Ron Rivera in October, following the team’s watershed 27-23 win in Seattle. If the Panthers made it to the Super Bowl, would Rivera allow Robinson to deliver a cautionary address to the team, reminding them of the magnitude of their opportunity, and the potential cost of losing focus? How had Robinson come up with that idea?

“God laid it on my heart,” he says.

Rivera’s rift with Lovie, Bears behind him in Super Bowl return

Rivera gave the green light. And so, before the Panthers boarded buses for the airport last Sunday, Robinson stood before them in the team meeting room. Asked to recount the gist of his message, he says, “I wanted my guys to know, ‘cause I love this team, that hey – you’ve got a great opportunity here. Go ahead and seize the moment, and don’t, in this respect, be like me.

“Keep your focus! Don’t let your selfishness ruin what you guys have built.”

“It took a lot of guts, the way he put his pride aside to share what he did,” says running back Fozzie Whitaker. “Guys really took note of what he said, and took it to heart.” Robinson’s message gave the guys one more reminder “to keep our focus on the final goal.”

Rivera raved about the brief speech: "I think it is one of the bravest things I have ever seen a guy do … For him to step up and relive that, to tell the guys he was wrong and [lost sight of] the reason he was there, that’s a huge message. And a great message."

Did it take? So, far so good. As far as we know, no Panthers found trouble during their moments of leisure. Not so with the Broncos. On Tuesday night, in a sad echo of Robinson’s transgression, Denver practice squad player Ryan Murphy was questioned by San Jose police in a prostitution sting. (Murphy was not charged, but team officials chose to send him home, to minimize the distraction).

Manziel's disturbing situation keeps getting darker

It was with a mixture of sadness and incredulity that I watched Robinson’s Shakespearean fall from grace sixteen years ago. He was not, and is not, a sympathetic character. No one grasps that more firmly than he does. But he was at the apex of a remarkable career that was eclipsed by a single act of selfishness and stupidity.

Robinson was two years behind me at Colgate, where he lit up the campus with his infectious smile, and lit up opposing receivers in the secondary. Genie-Rob, as we called him, was walk-on who quickly established himself as the best player on the field. An undrafted free agent in 1985, he made the Seahawks by the skin of his teeth, then spent 11 seasons with them, twice making the Pro Bowl. In ’95 he signed with Green Bay, winning a Super Bowl with the Pack in ’97. His was a remarkable story – I took pleasure in telling it following a Falcons playoff win in ’99, and was accused by an editor of engaging in “a certain Colgate-centricism” – sullied by a single bad decision.

That has been his fate. This week, I asked him if it felt unfair.

“I don’t sit there and go, ‘Oh man, woe is me,’” says Robinson, who has come to look upon his arrest as a necessary trial and correction placed in his path by the Almighty.

The pain has subsided, but flares on occasion. The scandal he brought upon himself “is just a part of me. So I don’t say, ‘Oh yeah, I got over it,' because you don’t get over it. It’s like having a scar.”

McClain, Finnegan have fit right in with Panthers’ defensive identity

There’s another reason he doesn’t feel sorry for himself: He’s in a great place. He is highly respected inside the Panthers organization, with whom he finished his NFL career, and for whom he’s worked the last 14 years. He’s deeply fulfilled, also by his second job: He coaches football, wrestling, and track at Charlotte Christian High School (His best known pupil in track and field: an erstwhile hoops player named Steph Curry).

“A Christian school,” he says, a twinkle in his eye. “Isn’t that ironic?”

It isn’t, of course. The faith he embraces also directs its members to practice forgiveness. In the days after his fall from grace, some acquaintances fled from him, “didn’t want to be seen with me. And I get that.” Others leaned in, offering support Among them, the late Reggie White, who was his roommate on the road with the Packers.

“I’m not going to kick you when you’re down,” he told his former teammate. “I’m going to stand with you.”

Until he passed 12 years ago, White did stand Robinson, and walk with him, figuratively, in the slow journey to redemption.