Artist awash in the land of refugees

On the Greek island of Lesvos, Chinese dissident artist Ai Weiwei stands tall to support the refugees.

Another child washed ashore dead yesterday. "We are all refugees of some kind," the artist will later say. A drone hovers over the edge of the sea when the boats come in, there where the remnants of the three discarded dinghies that have successfully made the crossing since 4 am this morning lie-it's his tell-tale signature. It is 10 am and a sunny 2 degrees in Skala Sikamineas, on the northern shore of the Greek island of Lesvos in the Aegean Sea, the mountains on the coast of Turkey visible on the horizon. The 58-year old Chinese dissident artist and India Today Art Awards' International Spotlight 2016, Ai Weiwei, here since Christmas 2015, is standing in the spray as the fourth boat carrying refugees comes in, some already suffering stages of hypothermia. Behind him, staggered on the shore are five members of his team recording different angles with their phone cameras held with a nonchalant focus at waist level. The dissident learns to record surreptitiously, you will learn. Several refugees walk with a limp, some have to be carried out, all are at some stage of soaked-to-the-bone, yet shaking hands with the volunteers helping them out, in quiet congratulations at having found the other side. The wi-fi at camp is named 'Better Times'. The first thing they all want to do is to message home, even before getting warm. Almost all, points out Weiwei, have children young enough to dream of a better future. He is shocked. "On some boats you find children unaccompanied, that's crazy. When you have given your children away, that is when you have given up," he says.

In Pictures | Syrian refugee crisis: Artist Ai Weiwei poses as Aylan Kurdi for India Today magazine

"We were all refugees once"

An estimated 53,4665 refugees have crossed over into Lesvos since January 1, 2015 last year, according to the UNHCR; 34,647 in January this year alone, averaging 1,155 per day. On the day India Today was there, 1,194 refugees arrived. Of the arrivals, 55 per cent are Syrian nationals, 25 per cent are from Afghanistan, 11 per cent from Iraq, and 3 per cent from Pakistan. The Syrians and the Afghans do not get along and have to be sent to different camps. The cameras come and go. Actress Susan Sarandon was here over Christmas, but it is a long- term engagement for the citizens of Lesvos. Michail Dimitrios, a 40-year-old who runs a gym in Myteline town, says in the summer there were over 40,000 sleeping in the streets, washing their clothes and cooking in bus shelters. Many come with money in their pockets, professionally qualified, and not looking for charity. Lina, from Oxfam Greece, explains that this wave of migrants comes with their dignity even if they lack possessions. The town of 86,000, despite the evident discomfort in accommodating such large waves-and there are occasional grumbles from locals-is shouldering the burden so well that Greece has recommended its citizens for a Nobel Peace Prize. "Not only have refugees always come to our shores, our ancestors are descended from the population exchange of 1922 between Greece and Turkey. We have all been refugees once," Kostas, a 74-year-old local landlord shrugs.

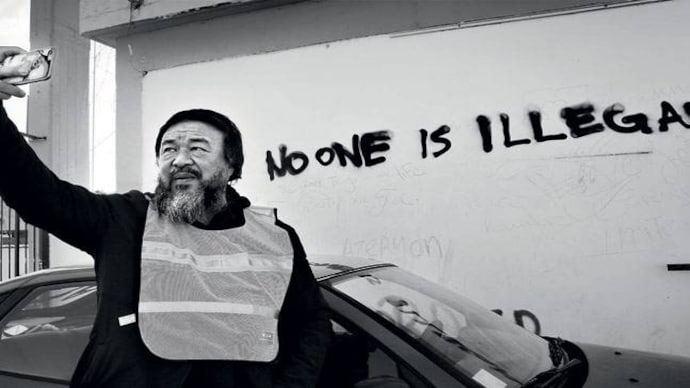

For refugees getting off the boat, it is not Ai Weiwei the artist who steadies their hand. He is not even so famous for many of the young volunteers from all over the world who stop to talk to this tall Chinese man in the water. A few recognise him: an Italian art graduate volunteer wants a selfie, a music graduate from UC Berkeley working with musicians here offers to lend him music, a London gallery owner's cousin name-drops in the hope of being on Weiwei's team, Nathan Scott-Peterson is a medical camp volunteer from England who wishes he could sneak him over the fence. But Sirkka from Switzerland whose hands are frozen from being in the water all morning, and Father Christoff Schuff in his brown orthodox robes, have no clue whom they are speaking to and ask after he's gone. Weiwei has recorded Father Schuff speaking of giving CPR to a woman and child off a boat, and burying four children in one day with Muslim rites on a plot of land in Yera, the most picturesque port in Lesvos. "This isn't about religion, this is about humans helping humans and I've only seen gratitude and respect," Father Schuff says. Weiwei's selfie-clicking, hug-handing genial presence here may bring international attention, but it also infuses ground efforts with bonhomie for those shepherding the never-ending waves. Once the refugees are sent for medical check-ups and warmth, Weiwei's team harvests the washed-up rubber dinghies divested of their engines, into pieces for a possible future installation.

"I was born like this"

In Moria, an hour away, refugees wait in volunteer-pitched tents on the slopes. The camp they line up to call home has three layers of military-grade barbed wire, and rolls of concertina on the roof, 16-metre high concrete walls and surveillance cameras. "It is a prison," Weiwei says. He watches refugees being treated roughly, volunteers turning themselves into authoritarian forces, putting people in line, commanding order and stopping filming. Last week, he was asked to delete all his recordings. Weiwei refused but his assistant lost everything. They've learned to recover it from memory cards and a local medic suggests they squirrel a microchip in cheek pockets. "It is all about control and how naturally man aspires to it," Weiwei says.

His guerrilla recordings, shot from outside the fence-he has not sought permission to shoot inside believing he will be given a sanitised version -will form part of Weiwei's video to be released online. "They ask why I have become like this. I don't have to become like this, I am like this. I was born like this," he says. It is assumed Weiwei became an activist-artist after his incarceration in Beijing by Chinese authorities during his investigations into fraud on the Sichuan Earthquake Names Project. But it goes beyond, to his father poet Ai Qang's hard labour cleaning public toilets and 20 years of being banned from writing poetry, which saw Weiwei live for five years in a hole in the ground between the ages of 12 to 17. Allegations of misappropriations raised against him, Weiwei was jailed at a time when he was considered too big to be jailed, left with a haemorrhage in 2009, sent as a message by Chinese authorities to those who would criticise them.

Himself a poet, an admirer of Rabindranath Tagore, a photographer and a professional blackjack player and well known for his friendships with poet Allen Ginsberg and Anish Kapoor, achieving collaborations with contemporary musicians and visual artists such as Olafur Elliason, Weiwei's work is unique to the counterculture movement and uses quirk to raise the resistance. When they moved to demolish his studio, he threw a party; when they jailed him, he responded with a single 'dumbass'; when they released him, he spoofed Gangnam style and danced. He is often criticised by some for being gimmicky, of making art that does not outlast its political statement, and of being a vandal, in his destruction of Han Dynasty vases in 'Dropping a Han Dynasty Urn', statements he makes to counter rampant consumerism and the dangers of glossing over the hidden past. Critics such as New York-based curator Francesco Bonami have said they "hate" Ai Weiwei for "exploiting dissidence in favour of promoting his art", even calling for him to be jailed. Ai Weiwei shrugs. "They are free to make art for art's sake and I respect that. I do not criticise them. I am not born an artist, I am born a human. I care about human conditions, rather than the opinions of others. I don't have a choice." He is evolving his own tongue outside the system, he says. "I'm trying to find a language which I am not familiar with, not feeding into traditional language, and I try to communicate through human instinct, ordinary people and their happiness, sadness, fear, imagination and fantasy." Though he would love to see that in galleries, it is here, in reality, that this is clear, he says. "If you are dealing with something new, the courage, sensitivity and skill are composite, and that is important for any artist, poet, writer. Otherwise it's not art, it just looks like art," he says.

"Most of the time, just provoke doesn't work''

Weiwei sees provocation as his instrument. "It is the artist's job to provoke ideas, to provoke aesthetic, ways of behaving, otherwise it's not relevant. If you think your art should be relevant, then provoke is always related to discovery, and related to finding a new language and skill." But he is conscious of its potential for failure: "Not every provoke will succeed. Only when you have profound knowledge about what happened before, in art, or culture, or politics, or human life, then maybe it will work. Most of the time, just provoke doesn't work. It's just attitude. And attitude can be very empty." Contrary to popular opinion, Weiwei, here at least, is devoid of attitude, a far cry from the Paris-Hilton- selfie-taking-larger-than-life artist the world sees him as.

Weiwei walks with such rapid strides across the camp on olive slopes, on the slush from human waste to melting snow, touching tent materials, looking at the layout, scoping for a good spot to shoot in, that even his young team cannot keep up with him. He cannot sit down or slow down. "I have a very strong conviction and motivation, and it keeps me moving," he says. He hands a child chocolate through the fence, his left hand never ceasing to film the queues, the officers, children playing with construction stone. He heads to the perimeter behind the camp, where registration queues are visible. "People don't question the loss of civil liberties because they pretend they don't know," he says. "That's why I am here. To say, 'this is reality'. That is why oppressions can exist, because there is very little opposition to it." When the Chinese crackdown on him occurred, he admits, very few actually stood up for him. Many make statements, but on the ground those who stand up for freedoms are rare.

"Artists have to become more human, not more political"

"Artists don't have to become more political, artists have to become more human," he says. If you're human, then in today's world, acquire your voice. "The job for artists is the freedom of expression, and if artists don't have the voice that will be tragedy," he says. When Weiwei recently attempted to buy Lego bricks in bulk to make portraits of dissidents, including one of Irom Sharmila struggling to free Manipur from AFSPA, the Lego company refused him the shipment. Weiwei took the appeal to Twitter and bricks poured in from across the globe. Despite the high-voltage reactions Weiwei invokes, no museum or gallery in the West would host his works. China, the might of its economy, looms despite his physical absence from its terrain. The West is no more a defender of free rights than the East is, he laughs. "The West exploits Third World countries because many nations in the West are not really defenders of democracy but use democracy as a cloak, a defending tool for their own profit." How Europe and the western world reacts to the refugee situation is a testimony to how they look at the human rights' condition, he points out. "The refugee situation reflects their understanding of essential human rights, made clear in the United Nations Treaty of 1952. You can see how much attention has been paid, how much money has been used in that and how much politics is played with that, it's shocking," he says. He recently shut his Danish show in anger against a law that allows the state to confiscate the valuables of refugees.

Though the West would like to think of itself as a more democratic space than an India or China, this is hardly true, as Weiwei has discovered the hard way. "They all say 'to maintain stability' or to 'make some kind of growth', but we have our rights to protect. We have to watch the government not to abuse its power, because it is given by us. That is every citizen's responsibility, of the media, and all kinds of artists. We have to react on it. Otherwise, we give up our basic rights. With no freedom of speech, the world can be horrifying," he says. To artists dealing with difficult governments, he advises: "Fight your way, all the way."

Himself an exile since the age of one, now living between Berlin and Greece, he is Chinese only in paperwork and language. For Chinese citizens, art has always been the language of the dissident. "I'm self-contained, I'm outside. It's not a desirable situation, but I've almost no choice," he says. "I don't see myself as a refugee because I've got my passport and can travel freely, and I'm better than refugees that have lost their lives. But in a way, many of my friends are still in jail, many of their families don't know where they are and they cannot have lawyers or proper records. In one sense, we are all refugees. I am not Chinese but I am a human artist, a human rights defender and that's a beautiful thing to defend and a condition we cannot afford to lose," he says. "Anything that will benefit a person or a society I will defend," he says.

Weiwei isn't obsessive about his activism. It uproots him. "I have a seven-year-old boy, I'd much rather spend time with him in a park. I brought him here two weeks ago. This is not my joy, it's painful to be here. But I cannot pretend not to see it," he says. He's taken to calling the internet his one true home. He credits social media, Twitter and Instagram, with giving him his voice. He uses it extensively in his work. Its ephemeral quality, the inability to save the responses it provokes, builds itself into his art like a new-age installation of its own kind.

He has ceased to believe in the material and textures and techniques of traditional arts, and uses them, as with the silk and bamboo that forms a halo of surveillance at Bon Marche supermarket, Paris, to satirise lack of movement. Every generation of artists must find their own language, he says. His activism extends to breaking out of the gallery system. Locating his work at Le Bon Marche itself cocks a snook at traditional circuits. "I think the system is too broken, too old and too corrupted. I don't believe in any system actually unless it can self-renew. To do that, they must focus on the individual, take a conscious understanding of what art is about, what culture is about, not just about power or money."

Ai Weiwei has no studio in Lesvos. "The world is my studio, this seashore is my studio," he says.