The road to Behmai begins where the golden mustard fields of Sikandra end, making way for sandy ravines and scruffy vegetation. About 40 families live in the village, in small red-brick homes, and rear cattle and goats. Less than 100 km from Kanpur, the largest city of Uttar Pradesh, the village has little to its name other than its bloody past.

Earlier this month, that past came back to haunt the village when, during a hearing at the Kanpur (Rural) court in what came to be known as the Behmai massacre, led by Phoolan Devi, one of the accused was pronounced to be a juvenile. In a fortnight, it will be 35 years since the shootout that left 20 men of the village dead. The trial is still on in the case.

Phoolan and her gang had attacked Behmai to avenge her gangrape allegedly committed by upper-caste Thakur men in the village. She, however, never faced trial for the massacre as she and 10 of her gang members surrendered before the Madhya Pradesh government in February 1983 under an amnesty scheme.

She spent 11 years in Gwalior Central Jail and was released without any trial in 1994. Then Uttar Pradesh chief minister Mulayam Singh Yadav withdrew all the criminal cases, including Behmai, against Phoolan “in public interest”.

Those still on trial, apart from the “juvenile” (now 50), are four ex-members of Phoolan’s gang — Bhikha, Phosa, Ramavtar Singh and Shyam Babu. They are being tried for dacoity and murder.

***

With almost all the men in the village killed or injured in the attack, Behmai was a village of widows (Express Photos by Gajendra Yadav)

With almost all the men in the village killed or injured in the attack, Behmai was a village of widows (Express Photos by Gajendra Yadav)

That’s a travesty, say people of Behmai, who witnessed the killing and who, now aged and ailing, still remember it vividly.

With the exception of cellphone connectivity, little has changed in the village since that day on February 4, 1981. With no electricity, at sundown, Behmai plunges into darkness. The nearest bus station is 14 km away down kutcha roads and the closest primary health centre (PHC) is a two-hour walk. Those seriously ill are taken to the PHC in tractors.

It was to this PHC that Janter Singh was taken that day, though in a bullock cart. Then a student, he was among the 35-40 men of the village, he says, whom the Phoolan gang rounded up and opened fire on.

A key prosecution witness, Janter says, “We were all rounded up near the village well. I clearly remember seeing Phoolan, Man Singh, Phosa and Bhikha standing before us and cursing us. They asked us who among us had leaked information to the police. When nobody spoke, they decided to shoot us. What happened next was not clear for a few minutes. There was smoke from the guns, blood all over and dust rising from the ground.”

It was when the dust settled that he realised he had escaped the shooting. “I heard Man Singh asking his men to check if anyone was still alive. I lay motionless. After a few minutes, when I opened my eyes, I was looking straight into Man Singh’s. He said, ‘This one in the lungi and baniyan is alive’. I was not afraid, I told him he and his gang had betrayed the villagers by firing at unarmed men who had agreed to cooperate. He then placed his gun on my chest, looked straight at me and fired,” Janter, now 56, says.

But the bullet didn’t kill him. With almost all the men in the village killed or injured, it was his aunt who drove the bullock-cart with him.

“I had not lost consciousness until I was put in the cart,” says Janter. “Women of the village had never driven a cart before. But I told my aunt to join the yoke and the cart and that the bulls would do the rest. As the cart moved slowly, I lost consciousness.”

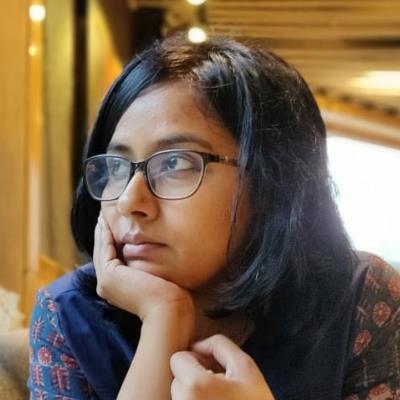

Janter Singh, a key prosecution witness in the case, was among the few who survived that day

Janter Singh, a key prosecution witness in the case, was among the few who survived that day

Janter, who readily yanks up his shirt to show the bullet scars, now lives 35 km away from the village, in Shastri Nagar, and works as a peon in the sub-divisional magistrate’s office at Bhognipur.

“There is no justice for the poor in this country. The trial begins after 30 years and one of the accused is declared a juvenile 35 years later! How are we even expected to hope for justice?” he says.

Rajaram Singh, 68, hid on the roof of his house when the gang came. “Nobody could see me but I could see what was going on. Now the court thinks that one of the perpetrators was a juvenile back then, and we don’t even get to know! This feels like a cruel joke.”

Janter claims he remembers seeing the juvenile coming with the other gang members. “He had pushed my aunt who was carrying a tray of cow dung on her head and it had splattered on the ground. He could not have been less than 21 at the time. When you see a teenager, you know he is one,” he says.

“If he has produced certificates and marksheets to show he was a juvenile, we will do our best to produce evidence to show that he was not. We cannot let this go,” says Uday Veer Singh, whose uncle was among the 20 men killed that day.

Hearing the talk, Jagrani Devi, 65, speaks up from the cot she is sitting on outside her house. “Will he (juvenile) not be punished?”

Talking about that day, she says, “I was standing right here when they came. My brother-in-law told me to stay inside the house. They came like a storm. I saw Phoolan Devi shouting ‘Jai Maa Kali’. They took everything from our house; even the pots and the utensils. They had tied a cloth across their shoulders to collect their loot.”

Wrinkled and frail, Tara Devi, another villager, says, “No one cooked anything in the village for eight days after the incident. Food kept coming from neighbouring villages for the children. It hurts that justice has been delayed. Maybe not to our children who were too young to remember anything, but it still matters to those of us who witnessed it.”

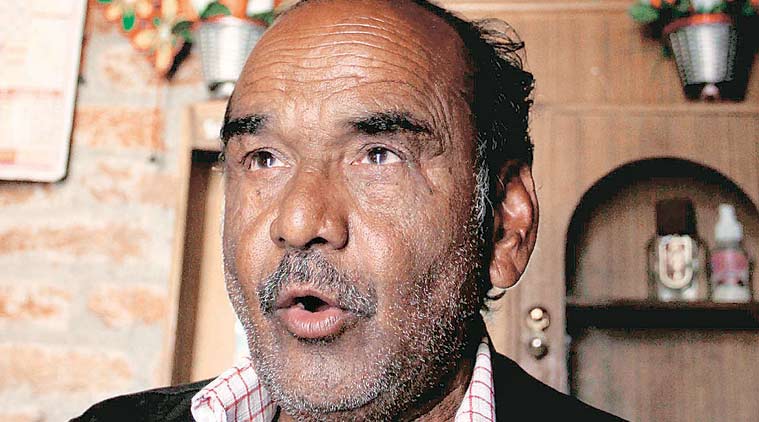

Beyond the village boundary wall, on the road that leads to the banks of the Yamuna, stands a memorial built in the memory of ‘martyrs’ of the Behmai massacre. It names the 20 Thakur men who were killed, their ages between 16 and 55. Of the 20, 18 belonged to Behmai, one each to nearby Rajpur and Sikandra.

Behmai still has only Thakurs with the exception of two families — one a Brahmin and the other a Dalit.

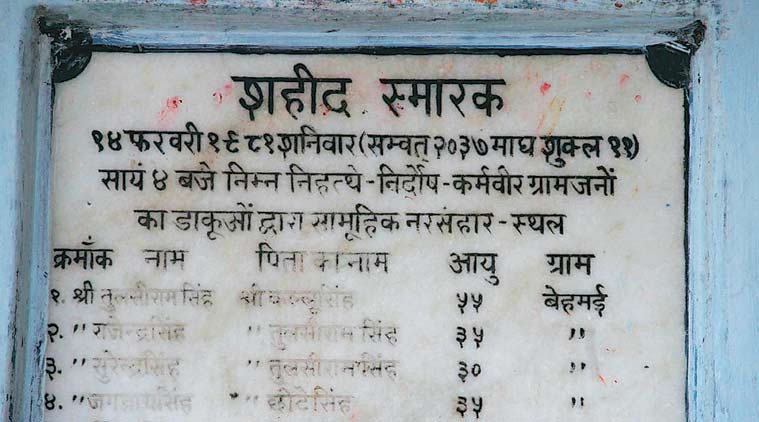

The plaque at the site of the massacte lists the names of the dead

The plaque at the site of the massacte lists the names of the dead

The plaque records that on the evening of February 14, 1981, at 4 pm, a gang of dacoits had killed “nimn nihatte nirdosh karmveer (the following unarmed, innocent, noble” villagers at the spot.

Behmai knows the grudge Phoolan held, of being kept captive and being repeatedly raped by the village’s men after her gang was attacked by rivals and she was brought to Behmai.

“She may have been wronged. But an entire village or all the members of the same caste cannot be labelled offenders and killed in cold blood. Each finger is different from the other,” says Janter, the prosecution witness.

He also claims that Phoolan started calling the incident “revenge” only when she entered politics. “This was taught to her so that politically she is not vulnerable. They were bandits and dacoits. That was a different time. They were fearless and lawless. They looted our village and killed 20 unarmed men. That alone is the truth.”

Another resident, Omkar Singh, says it’s easy for others to see her as wronged. “When women say their modesty was outraged, it makes them look like the victim. We don’t know how much of it is true. But does that mean crimes committed in the name of revenge be condoned? She was glorified as a heroine in the media. Does that mean 20 deaths will be forgotten?”

The BSP’s Indrapal Singh won the 2012 Sikandra seat in the Assembly elections, with the BJP coming in second. The ruling Samajwadi Party (SP) was third. Indrapal, who claims to have visited Behmai several times, says that as a politician, there is nothing that sets Behmai apart from the other villages in his constituency.

There are 750 villages in my constituency. The entire fund cannot be allocated for the development of one village, it has to be equally distributed. The entire area is in need of development and we have repeatedly brought this to the attention of the government in Uttar Pradesh. But our hands are tied because we are the Opposition and this government listens to no one,” he says.

The anger against the SP runs high. That’s not just because of the pardon Mulayam gave Phoolan. “Mulayam was the first to visit Behmai after the massacre, but after that, it just didn’t seem to matter to politicians,” says Janter.

Phoolan had joined the Samajwadi Party and was elected to the Lok Sabha in 1996. In 2001, in petitions filed by the families of those killed in Behmai, the Supreme Court directed that if she wanted relief from the cases against her, Phoolan would have to surrender before the Kanpur court. However, she was killed outside her residence in Delhi in July that year, before she could honour the court directive.

***

Phoolan Devi’s sister Rukmani Devi (left) and their mother Mula Devi at Ghura ka Purva. They have a different account — they say Phoolan never killed even a bird

Phoolan Devi’s sister Rukmani Devi (left) and their mother Mula Devi at Ghura ka Purva. They have a different account — they say Phoolan never killed even a bird

Phoolan Devi’s village is less than 20 km from Behmai. Unlike Behmai, Gurha ka Purwa, where she was born, is lined with mustard fields. Roads leading to the village are tarred.

At the village entrance, a 50-year-old is waiting for a car and saying her goodbyes. At least 20 people are seeking her blessings and seeing her off. She is Rukmini Devi Nishad, Phoolan’s elder sister, and bears a strong resemblance to Phoolan. With the 35th anniversary nearing, she had been expecting the media to come, Rukmini says, before adding pointedly, “We would have expected the media to reach much sooner.”

Rukmini, who lives in Gwalior, had been visiting her mother and younger sister Ramkali who live in Gurha ka Parwa. She has to leave now for the Kalpi railway station before heading for Lucknow, but settles down next to her mother Mula Devi on a cot at the entrance to the village. And begins telling Phoolan’s story.

“Phoolan and I were very similar, just like each other. As children, both of us worked hard in the fields to make some money for the family. But I was always healthier than her, she was skinny as a child,” she says.

Mula Devi, a widow and mother of three daughters and a son, lives with Ramkali’s family. Rukmini and Mula Devi walk down a narrow and winding lane to a decrepit brick house. It’s here that Phoolan stayed until she was married at the age of nine to Putti Lal, a man in his 30s. Pointing to a courtyard stocked with hay, Mula Devi says, “Phoolan used to grind grains in this courtyard when she was little,” she says.

The marriage to Putti Lal, who lived in nearby Maheshpur, has long been blamed for the start of the Phoolan story. Rukmini agrees. “Phoolan was Putti Lal’s second wife. He was first married to my mother’s sister but she expired. Then Phoolan was married to him but he said he could not keep her because she was a child and he did not want to look after her. He married again, this time to an older woman. He wanted to get rid of Phoolan so that she didn’t create trouble when she was older.”

She refuses to talk about claims of her sister being sexually abused by Putti Lal, but insists Phoolan was married only once. “This talk of her marrying some gang member in jail is all cooked up. There was no other marriage.”

The family has a different account of Behmai – from Phoolan’s rape to the massacre for which she was blamed. Rukmini says her sister had told her about being raped by two men when she was held in the village. “She never mentioned anyone else. Whether the relatives of these two men did anything wrong with her, we don’t know. But this is all Phoolan told me,” she says.

In the “revenge” massacre, the family adds, Phoolan had no hand. “They just used her name. They said Phoolan ka gang tha. But she never killed a bird even. The others may or may not have done it but Phoolan was never involved in any killings,”Rukmini says.

Rukmini was herself married at the age of 11. For all the things that went wrong in their lives, she blames the poverty the family faced after her father’s first cousin allegedly usurped the mustard fields belonging to them. “He took it saying there was nothing in my father’s name. But the village khasra records show it was my father’s. We have contested their claim before the district magistrate. It is yet to be resolved,” says Rukmini.

After Phoolan’s death in 2001, she formed the Pragatisheel Manav Samaj Party, an initiative to take forward Phoolan’s Eklavya Sena, which claims to help poor farmers in Gorakhpur and Purvanchal. It’s not just Phoolan’s political legacy that Rukmini has claimed. Of Rukmini’s three sons and daughter, one, Santosh Kumar, had been adopted by Phoolan. Rukmini insists Phoolan be remembered as someone else — “the messiah of the poor”.

“The roads came to this village because of Phoolan. There is a temple Phoolan built for our community… She was an MP from Mirzapur so she could not have used funds allocated to Mirzapur for the development of Gurha ka Purwa. But all the money she made from the proceeds of her films she used it for the development of our village.”

Pulti Lal Kevat, an elderly man sitting on a porch nearby, nods in agreement. “Our village made a name for itself because of Phoolan.

***

On a pitch dark evening, a 50-year-old man returns to his house in Maheshpur, 10 km from Behmai, after ensuring that his gram fields, a few hundred meters from his home, are protected from grazing animals. “They are a menace. They destroy a lot of crops,” he says, perched on a plastic chair brought from the house of his brother next door.

Clad in a crisp white shirt, white trousers and black woollen vest, the man declared a “juvenile” at the time of the Behmai massacre denies having been associated with any gang of dacoits, let alone Phoolan Devi’s.

He is among the five facing trial in the case. It was in November 2015 that the district court in Kanpur (Rural) accepted the application he filed in 2008 to declare him a a juvenile.

“My name is the bane of my life,” he claims, adding he had no knowledge of any attack on a village where 20 Thakur men were shot dead. “I saw it in the movie Bandit Queen. I don’t know any more than that… The killing of so many people by dacoits in Behmai was wrong. It should never have happened.”

It was his namesake, according to him, who was part of the Behmai massacre and who has been absconding since.

“I was a student. On March 30, 1981, the pradhan of our village and an elderly gentleman came to my school to call me back to the village. My school was in Umerpur, 2 km from the village. When I came back, policemen were waiting for me. They took me into custody despite villagers protesting,” he says.

In four months, he got out on bail and privately took his Class X examinations but failed. “I wanted to be a teacher and teach subjects like Hindi and mathematics in a private school. I was also a very good athlete. Ever since I was made an accused, my life has meant little apart from labouring in the fields and making the rounds of court,” he says. He once owned 4 bighas but all had to be sold to get his four daughters married, he says. He now lives with his wife, son and daughter-in-law.

He says the news that the court had declared him a juvenile offender is the first happy one in a long time. However, the Uttar Pradesh government plans to challenge the decision in the Allahabad High Court.

Additional district government counsel (criminal) Raju Porwal says the trial court erred in declaring the accused a juvenile. “We have already decided to file a revision application in the High Court. It has been sent to the district magistrate.”

Girish Narayan Dubey, the defence lawyer for all five being tried in the case, explains that the initial FIR lodged in the case on February 14, 1981, named three others apart from Phoolan — Lallu, Mustakin and Ramavtar Singh — as well as 35-40 “unknown persons”. While Phoolan was pardoned, the remaining three named were killed in “encounters”. It were the “unknown others” registered in the FIR that led to his clients being booked, claims Dubey.

According to him, these names were decided based on statements of other accused or personal rivalries in the village and a faulty identification parade.

Porwal, who insists the trial is “in its last stages”, argues that while there was no recovery of any loot from Behmai, police seized bullets from the spot as well as three letters allegedly written by the gang.

“In those days, dacoits used to leave their mark in the villages they attacked by leaving letters with the name of their gang. This was to instill fear. Three such letters left by Phoolan’s gang were recovered and are in the court’s record,” Porwal says.

Of the five on trial, Bhikha, Phosa and Shyam Babu were released on bail within a year of their arrest, while Ramavatar Singh continues to be in jail. “He too was granted bail. But he was so poor that he could not provide two sureties to fulfill his bail conditions,” says Dubey.

While Bikha and Shyam Babu are said to be living in Sikandra, Phosa, Dubey says, has become a “sanyasi”. “His family members have died and he is without a home. He wanders from one place to another and feeds on alms. He somehow always shows up in court on the date of hearing. But what he does and where he lives in between court dates nobody knows,” says Dubey.

The next hearing is on February 1.