- India

- International

Mrinalini Sarabhai: A life in motion

Looking back at the life of classical dancer Mrinalini Sarabhai, a cultural icon and a woman of many parts.

Mrinalini Sarabhai during one of the dance performances. (Photo: Courtesy Darpana Academy of Performing Arts archive)

Mrinalini Sarabhai during one of the dance performances. (Photo: Courtesy Darpana Academy of Performing Arts archive)

If you sit on the lawns of Chidambaram, the house that Vikram and Mrinalini Sarabhai built in Usmanpura on the banks of the Sabarmati river in Ahmedabad, you can hear the azaan as clearly as the temple bells. In Vatva, an industrial suburb of the city, a 22-year old Muslim man who runs a garage, owes his life to Mrinalini Sarabhai just as Radha Sridhar, 59, owes her her dance career. Yasin Mohammad Naimuddin Ansari was just eight years old, when he sustained 80 per cent burns from a cylinder blast during the communal riots of 2002. Mrinalini read his story in the papers and called Radha, who was running Prakriti, a voluntary organisation launched by Mrinalini in 2000. “We reached out to the boy, got him treated. He survived. We supported his education and two years ago, he opened a mobile store and now he works in a garage,” says Radha.

Radha’s bond with the celebrated dancer runs deep. It was Mrinalini who inspired her to perform her arangetram in 2005, 27 years after she had completed the Bharatanatyam course from the Darpana Academy of Performing Arts under her tutelage. She was 49 years old. Age, Mrinalini would say, “was only a number that changed every year”. “Amma told me, not to worry and I just went ahead,” says Radha.

From her barrister father Subbarama Swaminadhan, to her freedom fighter mother Ammu; her sister Lakshmi Sehgal, who went on to lead the women’s contingent in Netaji Subhash Chandra Bose’s Indian National Army, to her husband Vikram who founded India’s space programme, Mrinalini Sarabhai’s family was full of worthy stalwarts. Mrinalini herself stood out as a quiet revolutionary and a trailblazer. Deeply influenced by the freedom movement, by Rabindranath Tagore from her education in Santiniketan, and by her dance gurus Muthukumara Pillai and Meenakshi Sundaram Pillai, the classical dancer was a curious melange of Indian philosophy and western etiquette and a woman of many parts.

After her marriage to Vikram Sarabhai in 1942, she emerged as a cultural icon, an activist and a philanthropist in Ahmedabad. Like her father-in-law Ambalal Sarabhai, the textile baron who had supported Mahatma Gandhi’s freedom movement, Mrinalini would help the needy. “In the first winter of Prakriti, she asked me if we could distribute blankets to the street dwellers. We bought 200 blankets and gave them out,” recalls Radha. Meher Medora, 82, who runs the Apang Manav Mandal for the physically challenged, describes how Mrinalini was among the women she looked up to when she felt “old”. “She had a young mind and was always open to new ideas,”she says.

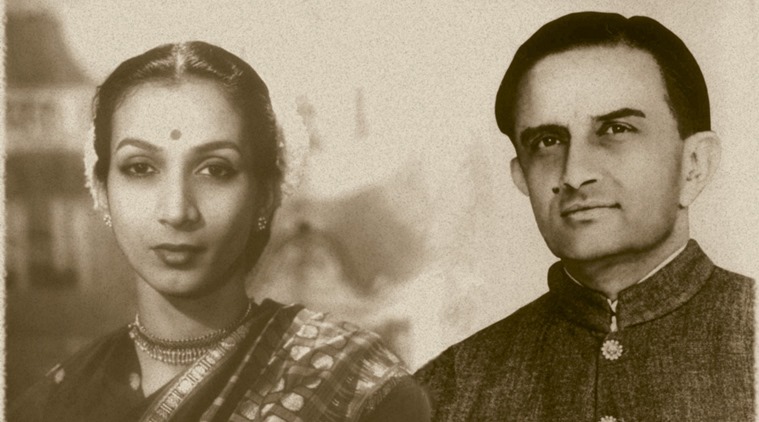

Mrinalini and Vikram Sarabhai. (Photo: Courtesy Darpana Academy of Performing Arts archive)

Mrinalini and Vikram Sarabhai. (Photo: Courtesy Darpana Academy of Performing Arts archive)

At home and outside, Mrinalini was a strict disciplinarian. She dressed immaculately and while she would not tolerate tardiness, she gave her children and grandchildren a lot of freedom. “In the middle of her drawing room, they put up this thing for children to climb and play on. She took it in her stride. I would not have liked it in the middle of my drawing room, but I saw how accommodating she was,” says Medora.

Integrity of character — be it in dance, architecture or personal appearance — was important to Mrinalini. “Amma was very exacting in her standards,” says Kartikeya Sarabhai, founder-director of Centre for Environment Education (CEE), and Mrinalini and Vikram Sarabhai’s first born. At Chidambaram, there was never an occasion where one was served “Indian food with a baked dish thrown in”. “She had a great repertoire of recipes and there would always be something nutritious at meal times,” says Kartikeya.

He also remembers, how, in the “pre-internet days”, he would look to his mother as “his Google”. “Sometimes, I would say, ‘Amma I am stuck’, while looking for environment-related quotations from the Upanishads. At the next meal, there would be relevant cuttings ready for me. I don’t know how she found it. She would always try to help me and Mallika out,” he says. His sister Mallika was always an activist, finding causes to immerse herself in. “Mrinalini used to equate Mallika with Mridula (Vikram’s firebrand sister who went with Gandhi to Noakhali in 1946) and said, you can’t stop her,” remembers Medora.

Mallika says her mother never pushed them to do anything, but kept a close watch over their activities. “Having been brought up in a Victorian way with an Irish nanny, she was a bit conventional, unlike Papa, but she allowed her children to grow and flourish,” she says. She remembers an incident when she wanted to go out for a movie and Mrinalini told her to go in a group of girls. If she went to a dance party, she would have to be home by midnight. “She used to say that after I turn 18, I could do as I please, but till then, she did not want people to give me a reputation that I did not deserve,” says Mallika. After their father’s death, she became even more protective. “She guarded us like a lioness. She might have disagreed with us, but she would never turn us out.”

In her autobiography, Voice of the Heart, Mrinalini writes about how she first saw Vikram as a young tennis player in Ooty in 1941. “To me, he looked like a Rajput painting come to life,” she wrote. A year older to Vikram, the two became the best of friends. In the beginning, Vikram told her, “Don’t let us fall in love. I do not want to get married,” and she had told him about finding her vocation in dance. Six months later, they were married and remained deeply committed to each other till Vikram’s death on December 30, 1971. He was only 52. By then, he had helped establish the Indian Institute of Management, Space Applications Centre, the Darpana Academy of Performing Arts, Vikram Sarabhai Space Centre, Thiruvananthapuram and other scientifc and cultural establishments in Ahmedabad.

Kartikeya, who was doing a PhD at MIT then, remembers the call he got from former bureaucrat TN Seshan, who was then director in the department of Atomic Energy. “‘I’ll give it to Mrs Sarabhai’, he had said. Amma came on the line and said ‘Papa’s gone’”. Kartikeya could not make it back home on time, due to a delayed flight. Mallika lit the funeral pyre, just as she did for her mother on January 21, alongside him.

As a young wife, Mrinalini often found herself bored by the staidness of life in Shahibaug, an old part of Ahmedabad, where The Retreat, her in-laws’ house, was located. In 1953, they moved to a new house, Chidambaram, in Usmanpura, a newer part of the city. “Her family was known for their dry Swaminadhan humour. She threw wonderful parties,” says Kartikeya. He recalls how Mrinalini had a curly blue wig which she would don sometimes and “dress up as a different person”. “She was not conservative, but preferred creativity built on tradition,” he says. As a dancer, Mrinalini was in love with Lord Krishna. “Her intense love for Krishna inspired her to write her mystic poem Kaan. In a world where there is much debate over Hindu norms, she was a devoted Hindu who considered tolerance as divine,” says Jayaraj Thayyil, her personal assistant since 2001.

Mrinalini with Kartikeya and Mallika. (Photo: Courtesy Darpana Academy of Performing Arts archive)

Mrinalini with Kartikeya and Mallika. (Photo: Courtesy Darpana Academy of Performing Arts archive)

Padmanabh Joshi, who works with the Nehru Foundation and whose book Vikram Sarabhai: The Man, the Vision, was the first published work on the scientist, recalls his first meeting with Mrinalini. “I had first seen Amma when studying in St Xaviers’ college in Mumbai, when she had come as a guest. A boy had performed a classical dance and everyone had laughed. Amma was furious. ‘Who told you that only girls can dance?’, she rebuked us,” says Joshi. Mrinalini went on to give them a lecture on the gender neutrality of classical dance. Today, her grandson, Mallika’s elder child Revanta, is a Bharatnatyam dancer, as is Mallika’s daughter Anahita, who famously went public with her lesbian status.

After Vikram’s death, Kartikeya says, “Amma would not share her loneliness or articulate it. She poured herself into dance, and created the Vikram Sarabhai festival in memory of my father.”

The family is yet to come to terms with her demise. “Yesterday, when we went to collect her ashes, Mallika instinctively said, ‘Call Amma’,” says Kartikeya. It was almost a throwback to how Mrinalini describes the day Vikram died, in her book. As people came to the Sarabhai home to pay their respects, she wrote, “Through all this sadness, the people and the crowd all around, I kept thinking, ‘I must tell Vikram.’ That thought has unconsciously persisted till this day.”

Apr 27: Latest News

- 01

- 02

- 03

- 04

- 05