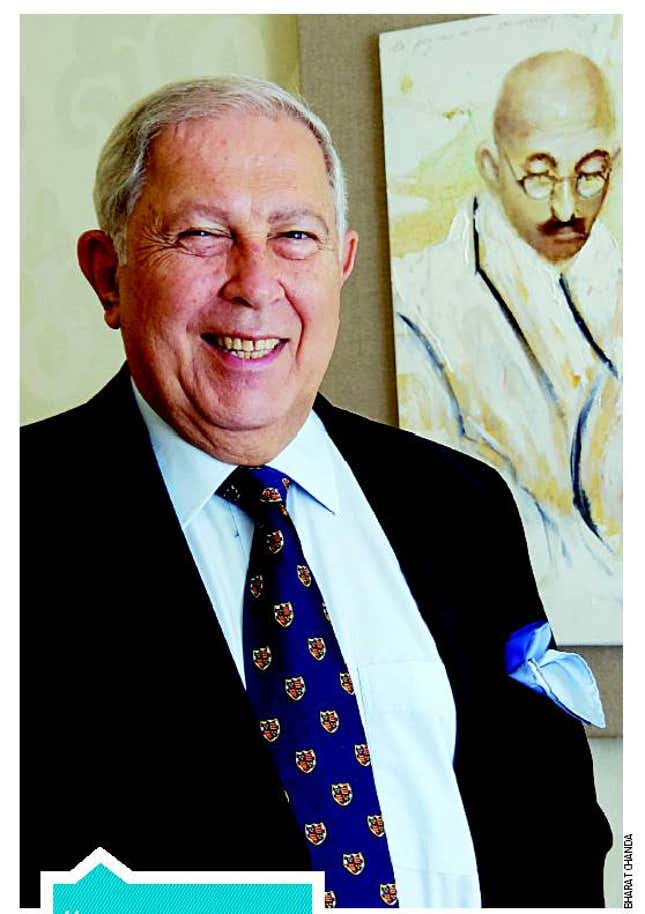

In 1992, the editor of The Times of India telephoned one of Mumbai’s most prominent businessmen—Yusuf K Hamied. The editor asked Yusuf, “as a Muslim leader”, his opinion on communal riots that were taking place in the city. “Why aren’t you asking me as an Indian Jew? Because my name is Hamied? My mother was Jewish,” Yusuf replied. His maternal grandparents perished in the Holocaust.

Yusuf, chairman of one of India’s largest pharmaceutical firms, is the son of an aristocratic Muslim scientist from India and a Jewish Communist from what is now Lithuania. Defined by his parents’ extraordinary marriage, he unites his father’s scientific skills, business acumen, and Indian patriotism with his mother’s compassion for the less fortunate. He charges the Western pharmaceutical industry with “holding three billion people in the Third World to ransom by using their monopoly status to charge higher prices.” And he has devoted himself to making life-saving inexpensive generic medications for the inhabitants of poorer countries.

Yusuf’s father

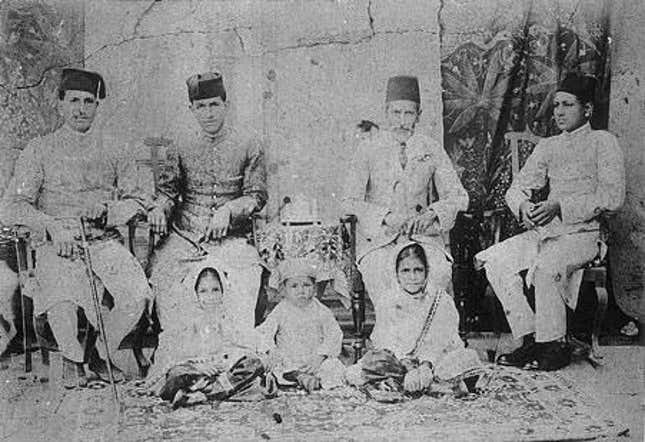

Yusuf’s father, Khwaja Abdul (K.A.) Hamied (1898-1972), was born in Aligarh. His paternal grandfather Khwaja Abdul Ali (1862-1948) traced his lineage through spiritual guides to the Mughal emperors of India back to Khwaja Ubaidullah Ahrar (1403-1490), a great Naqshbandi Sufi in Uzbekistan. His grandmother Masud Jehan Begum (1872-1957) came from the family of Shah Shuja ul-Mulk, the pro-British Amir of Afghanistan (1803-1809 and 1839-1842), whose family fled to India after his assassination in an anti-British uprising. Khwaja Abdul Ali’s uncle was Sir Syed Ahmed Khan (1819-1898), the great Muslim educational and social reformer.

Khwaja Abdul Ali entered the judicial service of the British government in India, but his son K.A. passionately opposed “the evils of foreign rule.” When Mahatma Gandhi’s Non-Cooperation Movement called for a boycott of government-run educational institutions, K.A. organised a strike at his school, Muir Central College. As a result, he was expelled from the university, then arrested when he tried to disrupt graduation ceremonies.

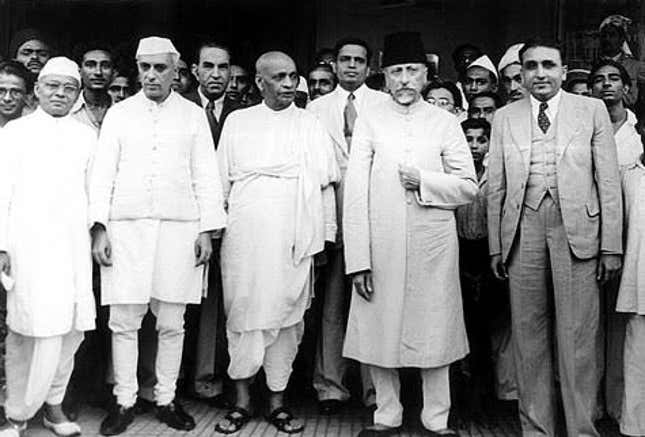

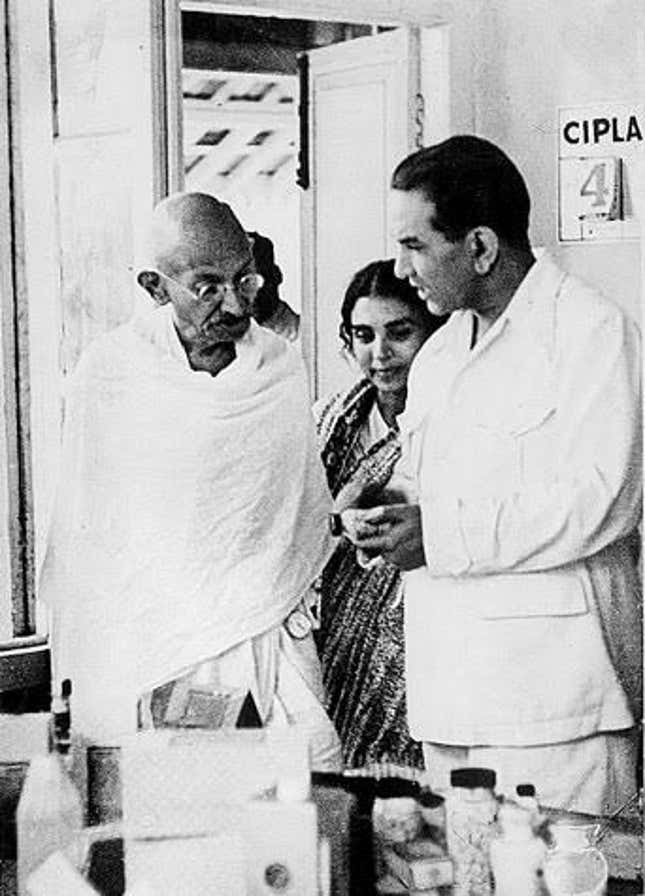

K.A. now returned to Aligarh, where Muslim nationalist leaders founded a new university, Jamia Millia Islamia, which refused government funding. He taught chemistry there. He also supervised the production and sale of khadi, or homespun cloth, which Gandhi had made a central element of Indian nationalism. At his maternal uncle’s home, he first met Gandhi as well as Motilal Nehru and his son Jawaharlal.

While teaching at Jamia, K.A. began a lifelong friendship with Zakir Hussain, later India’s president. K.A. and Hussain later left for Germany to pursue graduate studies. K.A. studied with one of the world’s leading chemists, professor A Rosenheim.

Yusuf’s mother

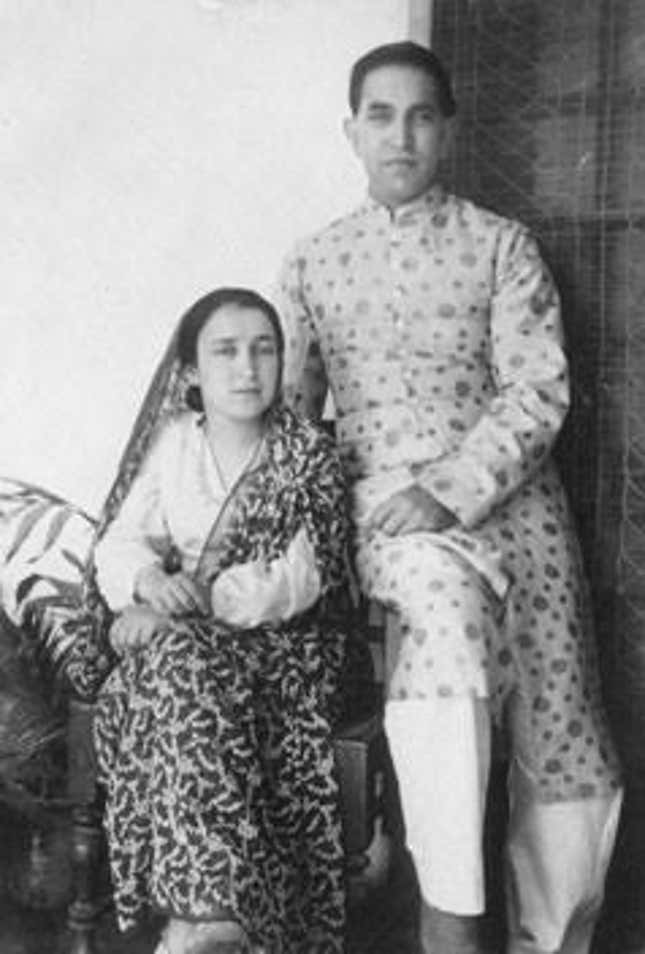

One day in 1925, K.A. joined some friends on a lake cruise near Berlin. One of the passengers on the boat was a young woman named, Luba Derczanska (1903-1991). Born in Wilno in Russian Poland (now Vilnius, Lithuania), she had come to Berlin to study. From their first meeting, the romance between K.A. and Luba blossomed. In 1928, they married in Berlin’s only mosque, and the following year they were again married in the Choral Synagogue in Wilno, and the marriage was “solemnised” at a register office in London.

Luba was active in Communist circles in Berlin, and sought to bring her Indian beau into the movement: the first gift that she ever gave Hamied was a postcard of Lenin and for a time the couple were regulars at party meetings. (In later life, K.A. had very strong reservations and concerns about Communism.) He was a prominent member of revolutionary circles in India.

Their parents were open-minded and welcoming, and the warmth with which Luba’s parents, Rubin and Paulina, greeted K.A. on his first visit to Wilno was matched by the welcome extended to Luba by Abdul Ali and Masud Jehan when she went to Aligarh.

Their son Yusuf was born in Wilno during his parents’ last visit there before the Holocaust. Yusuf is the Arabic form of the Hebrew name Joseph. It was the name of Luba’s grandfather, and hence pleasing to her family, as well as the first name of the Polish president, Józef Piłsudski, and so flattering to the K.A.’s Polish friends. A month after his birth, Yusuf’s parents took him back to Bombay.

Though Luba was not an observant Jew, Yusuf chose to memorialise her in the most active Indian synagogue. He heavily supported the reconstruction of the Shaar Hashamaim Synagogue in Thane.

Jews-Muslims partnership

K.A. defined himself as an Indian who happened to be a Muslim, and he became openly hostile to the Muslim League. He rejected the notion that Hindus and Muslims were “separate nations” as Jinnah argued. Unlike his brothers who opted for Pakistan, he always hoped for reconciliation in India between Hindus and Muslims.

In a speech to the inter-religious seminar in Delhi on Oct. 18, 1971, K.A. said that the “study of religion is my special hobby” and that “the basic attributes of this mysterious power, by whatever name we call it, are the same in all religions.” He quoted Zoroaster, Krishna, Moses, Buddha, Jesus, Mohammad, and Guru Nanak as “prophets” and said that “an ideal man must be a good man by virtue of his actions in society (and) may belong to any religion so long as he follows the tenets of his religion”.

K.A. always enthusiastically urged a partnership between Jews and Muslims. He loved to talk about Islamic Spain, where Jews and Muslims had joined to create a golden age, and once said that “if the Jews, with their wealth, knowledge and scientific skill and Arabs made a common cause, they would have a strong empire covering West Asia and the entire coast of South Mediterranean”. He even “asked president Nasser as to why he was seeking help from the communists, who were mulhids (non-believers in God) to fight Jews, who were nearer to Islam.” He always emphasised that “the Arabs and Israelis should see the necessity of getting out of this whirlpool of Russian and Western power politics” and “sit together at a round table conference away from Western powers to thrash out their differences and carve out a new future based on ancient friendship, alliance and mutual regard”.

The Holocaust

He regularly visited Germany, where he had many friends as well as business dealings. Once, Germans mistook him for a Jew and insulted him. He foresaw something far worse than discrimination and insults, and urged his Jewish friends to leave Germany. They insisted that, as members of the intellectual élite, they had nothing to worry about.

The horrors of the Holocaust were to touch K.A. and Luba directly. In June 1941, Nazi troops occupied Wilno, and almost immediately began the extermination of the city’s Jews. Luba’s siblings survived: her brother Zorach was working for K.A. in Bombay, and her Communist sisters had escaped to Moscow before the coming of the Germans.

However, the Nazis murdered her elderly parents who were unable to emigrate. K.A. tried to obtain visas so his in-laws could come to India. The papers finally came through two weeks after the Derczanskis were killed.

Their son Yusuf was very moved when in 2008, during a visit to his birthplace, Vilnius, he went to the Ponary forest, where German units massacred up to 100,000 people, the great majority of them Jews. Recently, he commissioned statues of Gandhi and his Lithuanian Jewish disciple Hermann Kallenbach in Vilnius. In honour of his mother, he sponsored a concert there by his life-long friend Zubin Mehta.

Yusuf, though focused on the lessons of the Holocaust, does not feel threatened personally as a Jew. He sees anti-Muslim mob violence in Bombay as particularly chilling, since to him it evokes the fear that Indian Muslims may share the same fate as European Jews. He remembers his father’s stories of Jewish friends who believed that their elevated place in society would protect them, and he says that Indian Muslims who echo this sentiment are as naive as European Jews were.

Most important pharma company

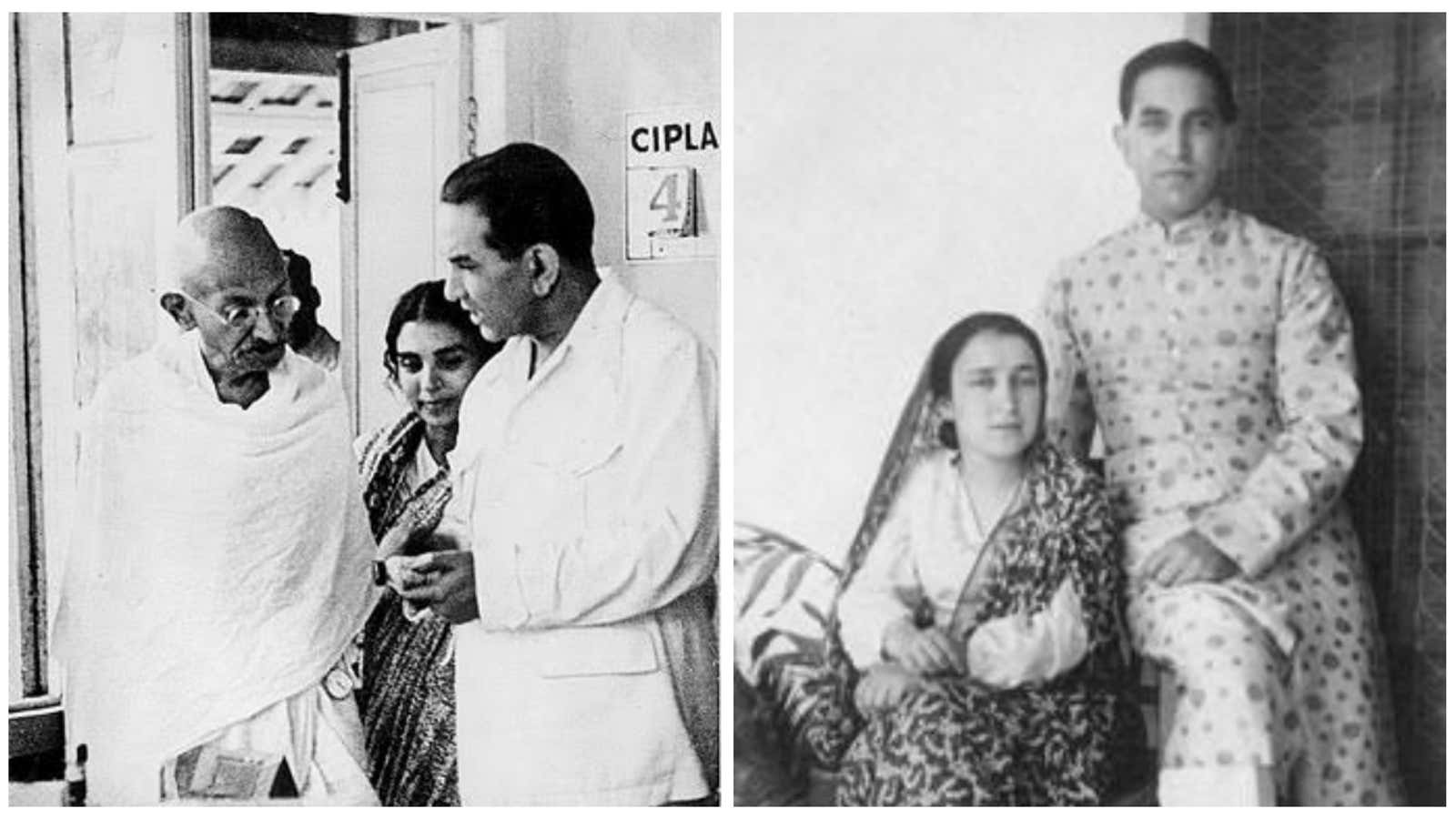

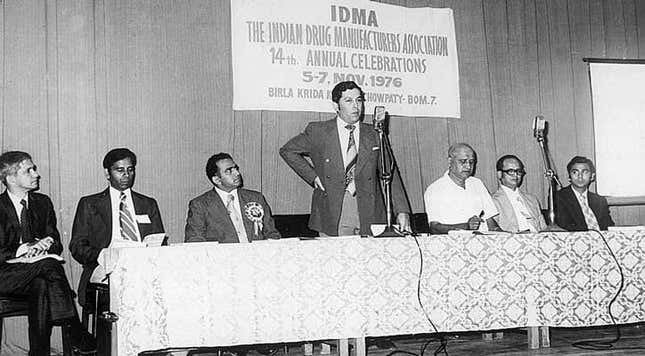

After several years in India, K.A. gained success as a businessman, and in 1935, he founded the Chemical, Industrial and Pharmaceutical Laboratories (CIPLA). It has since become one of India’s most important pharmaceutical companies.

K.A. had written in The Times of India on Dec. 11, 1964, that patent law should enforce “compulsory licensing” to other manufacturers to prevent monopolistic predatory pricing. Later, Yusuf picked up this same battle in the case of the astronomical pricing of AIDS medications by patent holders. By retro-engineering the first medication and anti-retroviral cocktail effective against HIV and AIDS and selling them at a fraction of the price, he helped saved millions of lives.

Perhaps with the murders of his own grandparents and six million other Jews in mind, Yusuf has called Big Pharma “global serial killers,” “traders in death,” and “death profiteers.” He sees the lack of access to life-saving medication by poor people in the developing world due to cost as a form of “selective genocide in healthcare” driven by Big Pharma’s desire for profits.

Note: A more comprehensive study of the Hamieds by the authors will be included in one of seven forthcoming volumes dealing with Jews in South Asia. This project, conceived by Kenneth X. Robbins, has already resulted in the publication of Western Jews in India and Jews and the Indian National Art Project as well as the current American Sephardi Federation exhibition, Baghdadis & the Bene Israel in “Bollywood & Beyond: Indian Jews in the Movies. Objects and Artifacts from the Kenneth And Joyce Robbins Collection.” Dr. Robbins is presently working with the Indira Gandhi National Centre for the Arts on a comprehensive exhibition dealing with Jewish communities in India and contributions to India made by Jews.

This post first appeared on Café Dissensus. We welcome your comments at ideas.india@qz.com.