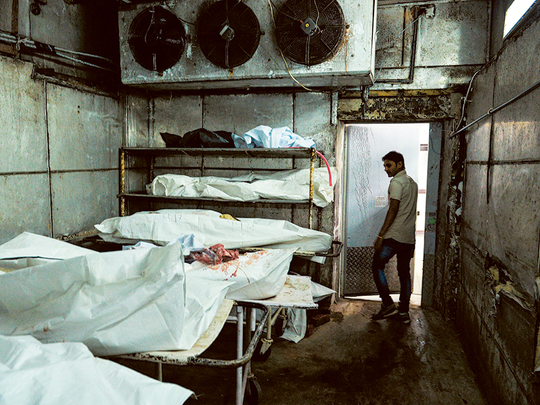

New Delhi: A rusted carving knife and a mallet lie on a steel table, while inside the cold storage rooms, bodies take up every square inch of the bloodstained floors.

More than 2,500 autopsies are carried out every year at New Delhi’s oldest and busiest morgue, but the air purifiers have long been broken and disinfectant supplies for washing floors ran out two months ago.

“The mortuary is compromised at every level,” Sabzi Mandi mortuary’s chief doctor, L.C. Gupta, said of the dearth of resources.

The decrepit state of the Indian capital’s dozen-odd morgues, mostly state run, recently stunned the High Court, which ordered the city’s government to take action.

From outdated equipment to poor storage of bodies and sick staff, the results of a court-ordered investigation made disturbing reading and shocked many in this deeply religious country.

“It’s a clear-cut case of negligence,” said lawyer Saqid, who uses one name, appointed by the court to conduct the probe.

“There are a lot of rights under the constitution and people in India spend a lot of time fighting for them,” he said as he poured over photos and documents in his office.

“But the dead cannot protest their rights.”

The crisis is compounded by the sheer number of unidentified bodies, several thousand a year, that fill Delhi’s morgues after being discovered outside train stations, bus terminals and other public places.

Many are homeless men who pour into the city of 16 million from villages every year desperately searching for work. They die from disease, malnutrition and the impact of living on the city’s harsh streets.

Protocol says they must be kept for up to 72 hours in a morgue to allow families time to collect them.

But many remain for much longer, unclaimed by relatives and shunned by the reluctant police who found them.

The crisis reportedly boiled over earlier this year when bodies were left on the street outside Sabzi Mandi, with frustrated staff refusing to take them back in.

Gupta denied the incident, but added that police moved quickly to come and collect unclaimed bodies after the row was reported in a leading Indian daily.

In the storage rooms, there are no shelves or racks to hold the numerous bodies. Encased in white plastic, most are lying on the floor, with many of the wrappings ripped and open.

A single, scuffed boot sits on top of one body and a hand flops over the edge of a rusted trolley holding another.

According to the court’s report, a key problem is the large number of autopsies performed at the request of overcautious police, creating a backlog and placing pressure on staff.

“Police insist on post mortems as a matter of routine even though their own circular says there is no need if there are no suspicious circumstances,” Saqid said.

Delhi’s health minister, Satyendar Jain, who reportedly said he felt ill after touring the morgues in the wake of the report, has promised to improve conditions.

Jain declined requests for comment, but his officials have said that a review of the situation is under way.

The court ordered the probe in 2014 after authorities discovered that the body of a prison inmate whose death was being investigated had been chewed by rats.

The report found that a lack of funds impacts on the living as well as the dead, with staff falling ill from handling bodies infected with tuberculosis and other diseases.

At Sabzi Mandi, staff use only bathroom soap to wash their hands, while a shortage of hospital-grade products means floors are cleaned instead with bleach, a doctor said.

“It’s an occupational hazard,” Dr Komal Singh said of staff falling sick at his mortuary at the Deen Dayal Upadhyay Hospital in Delhi’s west.

The morgue opened in 1995 with four medical officers and with resources for 400 autopsies a year. Now the same number of staff perform up to 1,800 autopsies annually.

With the court finally shining a spotlight on the crisis, Singh said he is hopeful the government will approve his request for more funds to double storage space for bodies and update equipment.

“People are interested in the treatment of the living, but in our society they don’t bother so much about what happens to the dead,” he said.

“But the court is taking this seriously and we are hopeful.”