- India

- International

Stones age: The story of artisans at Ayodhya

Down to a dozen and lower in expectations, artisans at Karsevakpuram, Ayodhya, chisel away for the Ram temple, as another December 6 comes along.

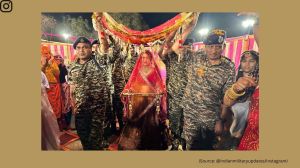

On Sundays, the artisans are joined by devotees who come to Ayodhya for ‘paanch kosi parikrama’. Some ask Sompura when would the Ram temple be built. He tells them, “It will be made once the BJP comes to power in UP”. (Express photo by Vishal Srivastav)

On Sundays, the artisans are joined by devotees who come to Ayodhya for ‘paanch kosi parikrama’. Some ask Sompura when would the Ram temple be built. He tells them, “It will be made once the BJP comes to power in UP”. (Express photo by Vishal Srivastav)

SINCE 1990, but for amavasya (new moon days) and a five-year halt, work has stopped at the Ram Janmabhoomi Karyashala in Karsevakpuram, Ayodhya, only once. That was on November 18, the day after the death of VHP international working president Ashok Singhal, who had spearheaded the Ram Janmabhoomi movement.

The VHP has since resolved to give a new push for a Ram temple at Ayodhya, starting with a big gathering this Sunday, the first anniversary of the Babri Masjid demolition after Singhal’s death. On Wednesday, RSS chief Mohan Bhagwat said “we need to be prepared and ready” to build the temple.

Karsevakpuram, however, shows none of the rush.

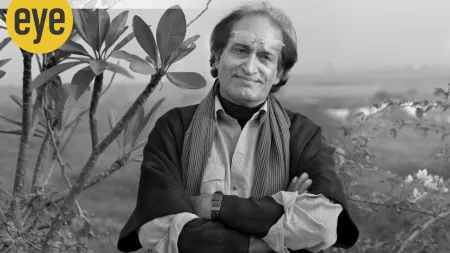

Under a tin shed, on a still, sluggish Sunday, Girishbhai Sompura is among the dozen-odd artisans now left working on stones for the planned temple. Once they used to number a hundred, he says.

At the back of the karyashala (workshop), run by the VHP, stones, carved for use in the proposed temple’s walls and roof, lie in piles. Much of the pink sandstone brought from Bharatpur, Rajasthan, has been lying in the open for years and is starting to blacken. A machine meant to cut stones lies defunct.

Sompura, who belongs to Ahmedabad, came to Karsevakpuram 23 years ago, ahead of the Babri demolition. Later, his family, including wife Meeraben and two daughters and a son, joined him. His children have since moved out, and last year, Meeraben died of cancer. However, the 20×8 room Sompura moved into in 1992, right at the centre of the three-acre-workshop complex, remains the same, as does his daily routine.

The room now has a TV, almirah, fridge and cooler, while other items lie loosely tied in around two dozen bags and packets, some on the part of the twin bed that Meeraben once occupied. The 60-year-old shares a toilet with the other workers and artisans.

Outside the room are piles of bricks with ‘Ram’ written on them, brought by kar sevaks from across the country, while right at the entrance of the karyashala complex is a model of the proposed temple.

Everyday, before beginning work, Sompura and the others visit a temple in the workshop complex for aarti, that includes a recitation of Hanuman Chalisa.

The chief mason, Sompura gets up around 6.30 am, and by 8 is at the aarti. Today, a Sunday, the artisans are joined by devotees who have come to Ayodhya for ‘paanch kosi parikrama’ on Dev Uthani Ekadashi.

Sundays are lazier days than most, so just four others join him in the tin shed, where the stones are carved. They idle around, only occasionally scrubbing stones carved by Rajnikant, a mason from Gujarat.

As a group of visitors clicks photographs of the artistes and stones, one of them asks Sompura when the temple would be built. Sompura smiles silently. Later, he says, “A lot of people ask this. They say now Narendra Modi has come to power, it should be built. I tell them that it would be made once the BJP comes to power in UP.”

Masonry is a traditional job for the Sompura community. Born in Ghatlodia, Ahmedabad, Sompura got into it in 1975, after failing to clear his Class X.

He had worked on a few temples in Ahmedabad, as well as in Belgaum (Karnataka) and Gwalior, when he met Anubhai Sompura, who had been to Ayodhya in 1990. Two years later, Sompura was on his way to Ayodhya, boarding Sabarmati Express with Anubhai and another fellow mason, Pradyumna. He still remembers it took him 36 hours to get to Ayodhya.

Sompura also remembers when the mosque was brought down. “I was working at this site. We thought then that now a temple would be built soon,” he says.

The place used to be buzzing with workers and artisans then, while visits by Ashok Singhal and Champat Rai of the VHP were common, Sompura adds. “Now there is no urgency, so work is slow.”

Between 2006 and 2011, the ordering of stones was halted and work had come to a stop, as there was no space at the workshop to store the stones. The work resumed a few months after the September 10 Allahabad High Court verdict on the Babri Masjid-Ram Janmabhoomi dispute. Sompura remembers Singhal visiting them then.

Each piece of stone has at least five flowers on it. “It takes a year to finish one stone,” Sompura says. Most of the temple will be in pink sandstone, with marble on the inside. Copper clamps are to hold the stones together, and no iron will be used. The plan is for a 250-foot-long, 150-foot-broad temple across two floors, topped by a shikhar (dome).

The money isn’t much — Sompura earns Rs 10,000 a month, having begun from Rs 3,000 in 1992; the labourers get Rs 325 daily.

However, it’s enough to keep him in Ayodhya. “At other places, I may have to sit idle for days. Here there is continuous work.”

In all these years, Sompura has not made many friends outside work. “Anubhai and these labourers are all I talk to. No one visits my room. Most of the time I watch TV or stay at work,” he says. Pradyumna is dead, while Anubhai is now in his 80s.

Sompura isn’t a VHP worker either. He stays away from all its agitations and programmes except for religious functions.

While his children are all settled in Gujarat, he doesn’t visit them often. “I go once or twice a year, only when I have some work,” he says. He misses his five-year-old grandson Dev, whom he talks to on the phone. “But when I ask him to come to Ayodhya, he says there are monkeys here.”

As a cook comes around noon to make food for him — he hired her after his wife’s death — Sompura tells her to only boil some milk for him. He is fasting for his wife.

There is little talk between Sompura, who is chewing paan masala, and the workers as they chisel stones till the workshop starts getting dark. Around 5 pm, Rajnikant packs his tools in a bag, which is a cue for the others too to head for their rooms. Labourers cover the seven stones they are working on with tin sheets. “Otherwise, the monkeys will defecate on them,” says Sompura.

In his room, Sompura lights a mosquito coil before removing the quilts spread on the bed, to make space to sit. His wife’s photograph hangs on the wall along with that of gods and goddesses.

As he struggles with his phone to show photographs of his children, he sighs, “They insist that I go back and live with them. But I say I will return once the temple is built.”

But even if the go-ahead comes now, Sompura realises, the temple wouldn’t be ready soon. “Work on 70 per cent of the stones is complete. When we get the nod for construction, we will get more workers. Still, the temple will take five years to finish.”

Preparing tea, Sompura flicks channels till he gets to Dangal. His favourite serial, Chandragupta Maurya, is playing.

Outside it is dark, and the other workers have retired for the night. Amid the muted buzz of television from their rooms, the only sound is of monkeys fighting with each other and jumping over roofs.

May 06: Latest News

- 01

- 02

- 03

- 04

- 05