- India

- International

Yakub’s Ramayana: A Muslim artisan and his rendition of the classic

For centuries, Muslim patuas spread across several districts of West Bengal have retold the epic through songs and scrolls.

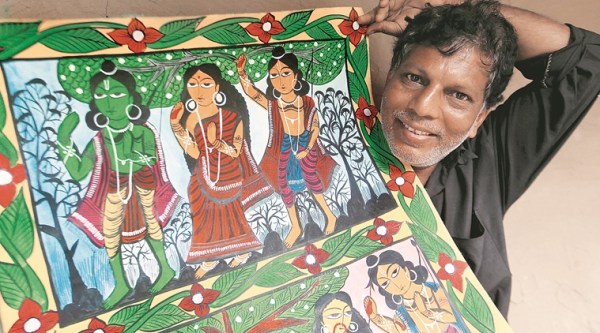

Yakub Chitrakar shows a scroll painting depicting incidents from Ramayana at his home at Noya in West Midnapore. (Source: Express photo by Subham Dutta)

Yakub Chitrakar shows a scroll painting depicting incidents from Ramayana at his home at Noya in West Midnapore. (Source: Express photo by Subham Dutta)

Diwali marks Ram’s return to Ayodhya, victorious from the battle with Ravan. Ahead of the festival this year, we look at the many versions of the epic, which has shaped our culture, arts and politics. It is a splendidly various tradition, from the rationalism of the Jain Ramayana to the humour of the Mapilla Ramayanam. It is both a political ideal and a deeply personal experience. It is the mega-story that contains a multitude of narratives of India.

Maybe it’s a case of divine intervention, maybe it’s just a happy coincidence. But the symbolism of his little hut in West Bengal’s Noya village being surrounded by Lokkhon trees is not lost on Yakub Chitrakar. The thorny fruits of the tree, named after Ram’s dutiful brother, have seeds which ooze an almost neon-red juice. The fruit and its name are of equal significance to Yakub, 59, who belongs to the artisan caste known as patuas (painters) or chitrakars (picture-makers). Their paintings include episodes from Bengali versions of the Hindu epics Ramayana and Mahabharata. “I don’t know how the trees started growing here. I have seen them since I was a little kid. As has my father; we use the seed to make dye for the painting,” says Yakub.

Watch Video: Yakub Chitrakar Sings A Section Of Ramayana

For centuries, Muslim patuas of this village, about 150 km from Kolkata, and a few others spread across several districts of West Bengal like Hooghly, Bankura Birbhum and Purulia, have retold India’s favourite story through songs and scrolls. “When I am singing and pointing out how Ravan repents his deeds as Ram is about to kill him, I am not a Hindu or a Muslim. I am just the story,” says Yakub.

The paintings are characterised by the use of bright colours and quirky narrative styles. Traditionally, each scroll is about 30 foot long, replete with intricate panels depicting scenes such as Sita’s abduction or Ravan’s death. The paintings are a part of performance and the chitrakar unfurls it to the accompaniment of the song.

Noya village, which is also inhabited by farmers and small-time traders, seems to be a picture out of an Indian tourism handbook. Ducks waddle in ponds, the facades of the mud huts are covered with intricate wall paintings and women and children sit under an imposing bel tree, drawing flat human figures on chart papers.

Sudha Chitrakar, 35, who has been painting scrolls since she was 12, stresses on the importance of practice. “When we are teaching our children how to make a scroll, we use chart paper. The paper used for the scrolls is handmade paper and absorbs colour more readily. It is then thickened with layers of cloth,” she says. Though traditionally chitrakars are men, today, women chitrakars are not uncommon.

“Painting a scroll is a family affair. Everybody contributes, including the women and children. Previously, men would be the only ones who would sing, but today some women are doing so as well. It’s good for the business,” says Anwar Chitrakar, 34, who lives a few houses away from Yakub.

Yakub Chitrakar painting scroll along with his family members at his home at Noya in West Midnapore. (Source: Express photo by Subham Dutta)

Yakub Chitrakar painting scroll along with his family members at his home at Noya in West Midnapore. (Source: Express photo by Subham Dutta)

As someone growing up in the village, it was not surprising that Yakub chose this profession. He was trained by his grandfather Banamali Chitrakar from when he was about seven years old. “My grandfather was a very well-known chitrakar. Quite a few museums have his work in their collection. He trained me not only with the paint and the brush but also as a singer,” says Yakub.

His knowledge of the Ramayana and other Hindu epics is an organic one, feels Yakub. “It’s not as if we were sat down and told the story at one go. My grandfather and father would paint one section of the Ramayana, and I would ask them what that meant; then they would explain it to me,” says Yakub.

He remembers the first panel he made. “It was a scene depicting Lakshman cutting Surpanakha’s nose. My grandfather gave me a lot of leeway but was stringent about one thing — he told me that Ravan had to be blue and Ram had to be painted green. This is very distinctive of the our depiction of Ramayana,” says Yakub. Initially, he was in awe of the hero of the epic, Ram, the maryada purushottam or the ideal man, but gradually he began to understand the complexities in Ravan’s behaviour. “I feel Ravan was a great hero marred by a fatal flaw, his arrogance. For a storyteller, he makes for a great character,” says Yakub.

Over the years, the topics of Yakub’s scrolls have changed. “During my father’s time, about 30 years ago, we used to focus on the Ramayana and Mahabharata. Another popular theme was the story of the Bengali snake goddess Manasa,” says Yakub. Since the chitrakars travelled with their scrolls from village to village, singing for alms and food, they tailored their scrolls accordingly. “When we visited Muslim-dominated villages, we would carry scrolls that recounts the lives of pirs,” says Yakub. Contemporary scrolls deal with a host of issues, from the destruction of the twin towers in New York City to the importance of family planning.

As he sings a section of Ramayana, Yakub takes on a different personality, his voice is almost primeval, devoid of any sophistry. “I try to reproduce my grandfather’s voice. It’s almost as if I mimic him. Similarly, if you hear my 17-year-old son sing, he will sound the same. This is how we have been singing for centuries,” says Yakub. While singing about the twin towers, his tone is more cheeky, almost playful. “One needs to innovate to survive,” says Yakub.

When it comes to the antecedents of the Muslim chitrakars, there are various theories. Medieval texts, such as the Mangal Kavya, suggest that the patuas were originally a Hindu caste who converted to Islam. Yakub says that is not the case with his family. “My ancestors were originally Muslims and came from a village near Dhaka. It could have been a famine in the village about 200 years ago that led us to settle down here,” says Yakub. He straddles two faiths, practising customs from each religion. “We offer namaz three times a day, but we also follow many traditional Hindu customs when it comes to weddings and other important ceremonies,” he says.

What does it mean to be a practising Muslim singing about Hindu gods and goddesses in India? Has he never faced any backlash? “Of course I have. But we have been doing it for generations. I heard that when we shifted to this village, the elders were resistant to the idea of Muslims singing about Hindu gods. But the zamindar of the area, who was a patron of art, persisted. However, even today, most Muslim families refuse to let their sons or daughters learn our craft,” says Yakub.

The other thing that shielded most chitrakars was their use of religiously ambiguous first names. “My grandfather used the name Banamali, which is a Hindu name. But I do not hide my religion. There is no shame in being a Muslim, then why should I?” says Yakub.

In 1991, when the Babri Masjid was demolished in Ayodhya, the chitrakars of Noya were protected by their Hindu neighbours. “As someone who makes a living out of Lord Ram’s life, I felt devastated. It might very well have been Ram’s birthplace, but was the bloodshed necessary? There are so many things about the epic that have various versions. Some say Ram’s arrow killed Ravan, some say it was Lakshman’s — that’s immaterial. The moral of the story is that good triumphed over evil,” says Yakub.

*The story was originally published with the headline Yakub’s Ramayana

Apr 25: Latest News

- 01

- 02

- 03

- 04

- 05