I didn’t go to Japan in search of the country’s cinematic history, but it kept coming in search of me. I was just there on vacation, traveling with the family of my daughter’s closest school friend, whose parents lived in Tokyo for more than 20 years and knew the city and the language well. For a week they squired the three of us around town, helping us to navigate the complexities of Shinto shrine etiquette, ramen automats, the confounding array of button options on every public toilet. (Which region of your netherparts do you want cleansed? For how long? At what temperature?) Then our friends left the country, and we traveled on our own to the ancient capital of Kyoto, armed only with Google Maps, a pocket phrasebook, and our wits.

A 9-year-old can only visit so many Shinto shrines. So at least once a day we would go to a fun-for-kids place, a variety of attraction in which Japan abounds despite a worrisomely declining population. One afternoon it was the multistory kawaii emporium Kiddyland, with whole individual floors devoted to Peanuts, the Moomins, Hello Kitty, and all variety of unknown-to-me-but-cute-as-all-get-out egg-shaped creatures with beseeching eyes. Another day we rented bikes and rode around the ingeniously designed Showa Kinen Park, where, among other curiosities, a mysterious water feature periodically fills a small valley with piped-in artificial fog. It would be just the place to get some expensive-looking effects for a low-budget J-horror flick, if any location scouts are reading this.

Photo by Dana Stevens

Wherever we went, Japan’s cinematic past kept sneaking into the present, the same way that fake fog unexpectedly turned a family snapshot into a still from Ringu. Not unlike Totoro—a forest spirit who appears and vanishes according to his own ineffable laws—the Japan I recognized from movies kept slipping out of sight whenever I reached for it, then darting from the shadows to surprise me again. The first place that happened, in fact, was at the Studio Ghibli Museum, where an 8-foot-tall Totoro peers out at visitors from the glassed-in box office. Opened by the animation studio in 2001, the museum has become an enormously popular destination for Japanese families—on the afternoon we went, we were the only Western visitors there. When we’d tried to reserve tickets online before the trip, they’d been sold out, and we had to send a kind Tokyo resident in person to wangle us a few precious entries.

Photo by Dana Stevens

Photography and cellphone use are politely but firmly forbidden once inside the Ghibli museum. Keeping phones in visitors’ pockets forces them to encounter the museum as an experience rather than a series of images—a fine metaphor for film itself, as the studio’s co-founder and anime pioneer Hayao Miyazaki seems to suggest in his playful-yet-serious manifesto on the museum’s website. “The building,” he writes enigmatically, “must be put together as if it were a film.”

My partner, a Miyazaki devotee, was a little disappointed to learn that the Ghibli Museum isn’t located at the place where the studio’s films are planned or created, and that it’s more of a cunningly designed play space for children than a learning experience for animation-savvy adults. He had been hoping for walls full of original animation cels, or maybe an exhibit documenting the studio’s working process from the storyboarding phase through the final edits.

But once I figured out the Ghibli Museum’s game—that it was, to quote again from the director’s manifesto, a place where “small children are treated as though they were grownups,” where exploration and play are privileged above discursive understanding—I let myself be enchanted by this compact, jewel-like space, full of handcrafted surfaces and absurdist touches. Light streams into the central lobby through a large stained-glass window featuring an underwater scene inspired by Ponyo. An unremarkable door tucked away near a staircase gives the impression of leading to a broom closet. Instead, if you open it, you’re confronted with a full-length mirror—a Lewis Carroll-ian architecture joke that made me laugh aloud in delight.

Photo by Dana Stevens

The first floor also contains a small cinema in which, every half-hour, visitors can watch a short Ghibli film created especially for the museum. The day we visited the museum was showing a 13-minute movie about sumo-wrestling mice—in unsubtitled Japanese, but nonetheless charming for that. In an example of the whole museum’s attention to detail and deep love of motion-picture technology, the tickets for admission to this minitheater are made of strips of celluloid. Held to the light, each ticket reveals three successive frames from a different Ghibli movie, reminding the visitor that these creatures that seem so alive are also optical illusions, a series of still drawings projected at a particular speed.

* * *

The Japan I knew before traveling there was almost entirely the Japan of the movies, particularly the country as viewed through a very specific slice of its long cinematic history: from the late days of silent film—which in Japan extended into the early 1930s—through the country’s “new wave” of socially conscious, youth-oriented films, which began simultaneously with the French New Wave in the late ’50s and lasted into the early ’70s. Tokyo was still, in my mind, the city of low wooden buildings crisscrossed with telephone wires and studded with radio towers in midcentury domestic dramas like Akira Kurosawa’s Ikiru or Mikio Naruse’s Late Chrysanthemums, both of which chronicle the painful breakdown of the old ways in the face of relentless modernization. It was the city of miniature models stomped into rubble and then burned by the fiery breath of Godzilla in the still-astonishing 1954 movie of that name, a howl of postwar anguish that doesn’t just allegorize but directly expresses the Japanese population’s still-raw PTSD from Hiroshima and Nagasaki—not to mention its mounting anxiety about U.S. hydrogen-bomb tests in the Pacific, the fallout from which had just ravaged the crew of a Japanese fishing boat earlier that year.

All three of those movies, and a huge number of others—just pulling titles at random, there’s Kurosawa’s Star Wars–inspiring The Hidden Fortress, Hiroshi Teshigahara’s avant-garde international hit The Woman in the Dunes, Nobuhiko Obayashi’s Z-movie turned cult-horror phenomenon House—came out of Toho Studios. In a film industry very different from that of classic Hollywood—where each of the major studios tended to concentrate on a particular stylistic brand (the socially conscious Warner Bros. crime picture, the sophisticated Paramount star vehicle, the chipper MGM musical)—Toho stayed busy for decades churning out every kind of movie. Grand-scale samurai costume epics. Delicate psychological portraits of aging geishas. Fifth-generation kaiju-movie ripoffs for the global market (Space Amoeba, released by Roger Corman’s American International Pictures as Yog Monster From Space). Middling action comedies for the Asian-only market (if only for the title alone, I find myself drawn to 1971’s Young Guy vs. Blue Guy).

That Tokyo—already an object of conscious nostalgia in the midcentury Toho films that chronicled its swift evaporation—is long gone. The telephone wires have burrowed underground in the form of fiber-optic cables running the length and breadth of what’s now, if you include the outlying metropolitan areas, the world’s largest megacity. The traditional wooden houses with gracious paneled sliding doors—great swaths of which were razed, Godzilla-style, first by wartime bombing raids and later by Cold War industrialization—have been replaced by modern skyscrapers as far as the eye can see. But the Toho film studio remains in operation, though it’s fallen on much harder times in recent decades, producing inexpensive TV shows and distributing anime with Ghibli and other partners.

With reminders of Japanese cinema everywhere—even the shiatsu and acupuncture clinic I visited bore the name of Akahige (Red Beard), which, as the brochure reminded visitors, was the title of a 1965 Toho-released Kurosawa film about a noble doctor—I felt the strong need to make a pilgrimage to Toho. I sought out the studio’s home in the quiet residential neighborhood of Setagaya, even knowing that Toho offered no public tours and that, in a culture as respectful of rules as Japan’s, I was unlikely to be able to glad-hand my way in at the gate. Maps and phrasebooks were useless in informing the cabdriver where I wanted to go. But the single word Gojira—Godzilla’s Japanese name—immediately clued him in.

Photo by Dana Stevens

As I had suspected, my attempts to explain to the guard at the Toho gate that I was an American film critic who loved Japanese movies and would be happy just to walk around for a few minutes thinking fondly of Toshiro Mifune were met with a courteous but impassive refusal. But Mifune was right there with us anyway, his image looming three stories high in a still from The Seven Samurai reproduced on the white, windowless wall that’s all Toho shows of itself to the world. This mighty simulacrum of the glowering, rough-voiced Japanese actor—Kurosawa’s longtime muse and the household god of Toho, who appeared in more than 100 of the studio’s productions over a period of 40 years—easily dwarfs the modest Godzilla statue nearby, which stands scarcely higher than the stuntman in a rubber suit who originally played him. His once-fearsome foreclaws raised in what almost reads as a gesture of brontosaurus-like supplication, Gojira seems to be saying: Welcome to Toho, the house I built—and then destroyed, along with the rest of the city, over and over for the next six decades.

* * *

Photo by Dana Stevens

In Kyoto my daughter and I made an unforgettable late-night trip to a sento, or public bath, that was reputedly one of the inspirations for the enchanted bathhouse at the center of Miyazaki’s Oscar-winning Spirited Away. Once a substitute for at-home bathing facilities as well as a local gathering spot, neighborhood sentos have been declining in popularity in the rapidly modernizing decades since World War II. Many of these small businesses are both run and patronized mainly by older people, so it’s possible Japan’s population will soon age out of this wonderful civic tradition.

P. and I spent most of our time at Nishiki-yu trying to figure out what it was about this particular sento that might have spurred Miyazaki to dream up the nightmare-like tour de force that is Spirited Away. Built in 1927 and now one of the city’s oldest continuously operating bathhouses, Nishiki-yu is a well-lit, threadbare, immaculately kept little neighborhood facility. There’s no sign anywhere of the ghostly spiritNo-Face or the evil witch (and exacting sento owner) Yubaba—much less a whiff of that malodorous river spirit whose unending flow of murky sludge threatened to flood the witch’s whole establishment. But somehow our visit still felt infused with a sense of mystery that may have had less to do with the bathhouse’s influence on the movie than with the movie’s influence on us.

It was nearly midnight, the sento’s closing time, which only lent to the mood of magic and, for my daughter, mischief. (When you’re traveling in a time zone 13 hours off from your own, the concept of “bedtime” quickly grows abstract.)

Our expatriate friends had advised us that Westerners have a reputation in Japan for iffy hygiene, so my daughter and I made a point of theatrically lathering and rinsing ourselves in the pre-bath area. Nishiki-yu offers a wider than usual selection of tub options, broken down by my daughter as follows: “ice-cold, normal bath temperature, Mom level of hot, super-face-meltingly hot, and weird electric water.” (That last was the denki-buro or electrified bath, which delivers a steady low-voltage shock that’s supposedly therapeutic and indisputably jarring.) There are a handful of brass wall spouts shaped like the heads of animals, but little else in the way of decoration. With one exception: Placed here and there around the otherwise unadorned white tile walls on the women’s side are pieces of clear tape, on every one of which appears the same sentence, handwritten in English in all caps: “YOU ARE IN HEAVEN.”

Unceremoniously taped to the wall at regular intervals, this assurance that we had, indeed, reached the promised land had the authority of a bulletin from the beyond. Anglophone visitor, you may not be entirely sure of your way back to your hotel. You probably should have taken off your shoes sooner upon entering the sento door. Maybe you and your child didn’t wash yourselves according to local standards and are even now polluting the Nishiki-yu’s pure waters with an unquenchable flow of river monster–like sludge. But the spirits chose to patronize this place for a reason, and you’d do well to remember the address.

The next time cinematic Japan popped up to make its presence known also had to do with a magical body of water. Back in Tokyo, we last-minute-splurged on three nights at the Park Hyatt, the austerely swanky hotel where Bill Murray and Scarlett Johansson pass like ships in the night in Sofia Coppola’s 2003 sort-of-romance Lost in Translation, specifically so our daughter could swim—a previous reservation at a more budget-conscious hotel having been scuttled when we learned its pool banned children. After swimming in this awe-inspiring facility, all I can say is that, when a terrycloth-robed Murray asks Johansson, “Cool pool, huh?” he is severely underappreciative of its charms. The glassed-in rooftop pool at the Park Hyatt Tokyo is firmly situated at the apex of all possible hotel pools past, present, and future. It was all any of us could do to get out of it long enough to explore the city.

Of all the times on our trip when the place I had come to think of as “movie Japan” seemed to collide with the place we were actually standing, it was the Park Hyatt that furnished the most frequent and comical instances of the phenomenon. Though Coppola’s second film came out more than a decade ago, the hotel—with its labyrinthine elevator banks; excruciatingly attentive staff; and aura of hushed, almost sepulchral luxury—looks, feels, and sounds just the same, right down to the giant bronze sculpture of waving reeds in the middle of an otherwise empty lobby. Especially after we rewatched the movie—because what better to do, on your second of three nights at the Lost in Translation hotel, than curl up with a laptop and watch Lost in Translation?—we couldn’t stop spotting its props and sets everywhere we looked. Every night we considered stopping off for a nightcap at the sleek lamp-lit bar where Murray and Johansson strike up their first conversation. (Then we remembered that sharing one cocktail there would cost about the same as a ramen-automat lunch for the whole family.) Every trip to the elevator took us past the small white house phone, tucked in a dim alcove just off the 41st-floor lounge, where Murray’s character, a washed-up movie star, makes his last call to Johansson’s room to say goodbye.

Photo via American Zoetrope

At the time of its release I remember not being totally won over by Lost in Translation, though it is still easily my favorite of Coppola’s films. For all the director’s impressive mastery of her aesthetic toolbox—the music, cinematography, casting, costumes, and, of course, location are all exquisite—there was something insubstantial about the script, particularly when it came to Johansson’s character, a dissatisfied newlywed who’s undergoing a photogenically vague spiritual crisis. The film’s treatment of its Japanese characters—or really, any character outside the charmed circle of Murray’s and Johansson’s tentative romance—also struck me as reductive and a little sour. (We winced anew at the running joke about the Japanese mixing up their Ls and Rs.)

But watching Lost in Translation in the curiously placeless place where it’s set (and from which the action departs only for a few brief set pieces) threw both the movie’s flaws and its strengths into sharper relief. For all its stylish anomie and unacknowledged privilege, Lost in Translation creates a sense of place as specific as any I can think of—and the place in question isn’t really Tokyo but the Park Hyatt itself, in all its starkly designed, impeccably managed, somehow alienating beauty. It’s the features of the hotel—the pool, the bar, the complicated elevators—that allow the two main characters’ paths to keep crossing until they begin their diffident but possibly life-changing flirtation. As much as it’s a love story, Lost in Translation is a movie about hotel life, and Coppola beautifully captures the aura of contingency and possibility that hovers around these strange institutions where private and public overlap. It’s unlikely my family will ever again stay anywhere as expensive as the Park Hyatt Tokyo (and I’m not sure I mind; the pool was worth the splurge, but all those hovering concierges got to be a bit much). But I doubt I’ll ever stay in any hotel again without feeling like I’m in a movie.

* * *

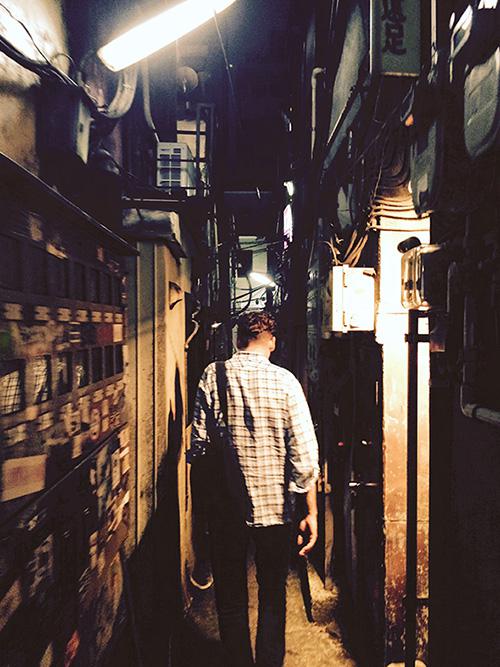

Photo by Dana Stevens

On our last night in Tokyo, I made one final pilgrimage. Tokyo’s Golden Gai district is a warren of narrow pedestrian alleys nestled deep in the canyons of Shinjuku (the neighborhood of neon-paneled high-rises that Murray traverses by cab at the beginning of Lost in Translation). Crammed into a stretch of low buildings just six streets wide are more than 200 tiny bars stacked one atop another, some seating fewer than a dozen people, each with its own distinct appeal to one or another of the countless obsessive subcultures the Japanese designate by the blanket term otaku.

Perhaps I should make that sub-sub-sub-cultures. One minuscule ground-floor bar displayed a film still of avant-garde director, ex-model, and former Björk companion Matthew Barney—naked but for a sort of penis-sock woven of green satin ribbons—beneath what I assumed to be the bar’s name: Cremaster Information. I wish now we had stopped there for a warm-up drink, because if there had been someone on staff who could explain the Cremaster movies to me, I would gladly have started a tab.

But my drinking buddy that last night in Tokyo—an American newspaper editor who’s lived in Japan for nearly 30 years—had a specific destination in mind, the place I had asked him to help me find in the Golden Gai labyrinth: La Jetée, a second-floor, 10-seat gathering spot for film lovers and filmmakers. A passionate young cinephile named Tomoyo Kawai founded La Jetée more than 50 years ago, and the gracefully ageless Ms. Kawai still tends bar there whenever the place is open, hosting, when they’re in town, such longtime regulars as Martin Scorsese, Francis Ford Coppola, Quentin Tarantino, Agnès Varda, and—until his death in 2012—Chris Marker, the French filmmaker whose half-hour-long 1962 masterpiece gave the bar its name.

Photo by Dana Stevens

When Ms. Kawai is out of town, La Jetée simply stays closed, and after ordering a single round there, it was easy to see why. Seldom have I been to a public establishment that was so evidently a manifestation of its proprietor’s inner world. Up a steep flight of stairs plastered floor-to-ceiling with movie posters—mostly canonical titles, but I think I glimpsed Nic Cage’s brooding face as well—is a minuscule, low-ceilinged room full of more movie posters and stills, carefully labeled VHS tapes, and a high wooden shelf with a variegated collection of those red-and-white good-luck cats lovingly memorialized by Marker in Sans Soleil, his extraordinary 1983 essay film about (among other things) Japan, travel, memory, cinema, and time.

Over glasses of chilled umeshu, or Japanese plum wine, we spent a few hours talking to the unassuming Ms. Kawai, who gradually revealed herself to be deeply knowledgeable and tirelessly curious about classic and contemporary cinema from around the world. That reveal was slow in part because after two weeks in the country I was still stumbling over the handful of Japanese phrases I’d memorized, and Tomoyo confessed a lifelong resistance to learning English. Most of the time she and my editor friend spoke in Japanese, stopping every few minutes to translate the gist for me. But after the umeshu kicked in, she and I would sometimes switch for a while into French, a language neither of us has mastered but that we both spoke well enough to express reasonably complex ideas.

I asked Tomoyo how, as a young woman working in the film distribution business, she had come to the decision to open her own bar (in a space she still rents rather than owns after five decades, an arrangement that seemed to suit her fine). “Je voulais être indépendante,” she explained simply. Unmarried with no children, she seems to have remained fiercely indépendante ever since, attending the Cannes festival almost every year—not as an industry insider or press rep, just as a lover of the medium—and getting to the theater several times a week to watch new releases or the programming at Tokyo’s repertory houses. She seemed to have seen everything and had thoughts to share about the 2009 Kazakh slice-of-life Tulpan (recommended), the late-career output of Wong Kar-Wai (skip My Blueberry Nights), and Parisian moviegoers’ undying passion for Blade Runner, which, we both recalled, stayed in full-time rotation for years on end at one theater in the city’s outskirts. When I told her one of my favorite films of the year so far was White God, a Hungarian political parable starring a pack of charismatic dogs, she looked skeptical but made a mental note of the title to add to her prodigious interior archive.

I kept meaning to press Tomoyo for stories about her best-known past and current customers. What kind of a drunk was notorious sake enthusiast Yasujiro Ozu? When Tarantino blows into town, does he pick arguments with random strangers about martial-arts film trivia? Is Varda really as impossibly cool as she seems, and could I please get her email and become her best friend? But I sensed that prodding Tomoyo about the moments other patrons had shared here would only interrupt or, worse, shut down our own conversation. It felt right to let the talk drift wherever it would, in and out of three languages and 10 decades of film history.

La Jetée appears in one scene of Marker’s Sans Soleil, filmed in what appears to be the ’60s or early ’70s. There are posters on the walls, but they don’t yet stretch from floor to ceiling. At the bar, a few patrons (including, presumably, Marker with his camera) drink and talk as a young woman behind the bar answers a telephone. It’s Tomoyo, I assume, though her face is only visible for a second under a curtain of Anna Karina bangs. On the soundtrack, the film’s narrator—not Marker, but a woman playing a semi-autobiographical character—talks about “the small bar in Shinjuku” that her now-absent lover used to compare with “that Indian flute that can only be heard by whomever is playing it.”

At first that analogy sounds as oblique as it is poetic. What does, or should, a public drinking establishment have in common with a barely audible woodwind? Shouldn’t the ideal gathering spot have the ability to be “heard by”—i.e., communicate its unique essence to—all its patrons at once? And who steps out on the town, especially in a place as legendary for its nightlife as Golden Gai, looking for an experience that in any way resembles a mythical Indian flute? But after a few hours at La Jetée, Marker’s odd image struck me as a precise evocation of this bar’s intimate spell. It’s a place that, like the mythical Scottish village in Brigadoon (or for that matter, like my daughter in the artificial fog), doesn’t emerge until it’s ready to be seen. Just like at the Ghibli Museum, the Toho Studios, the Park Hyatt hotel, and the Nishiki-yu bathhouse, whatever Japanese cinematic spirit I tried to go in search of kept disappearing down the nearest hole, only to pop up later in a slightly different guise. But whoever taped those signs to the walls of the bathhouse was right. It was heaven.