High-Tech Spark

Georgia is quickly becoming known as a hotbed of bioscience innovation.

Georgia has long been known for cotton and peaches, but a better symbol might soon be stem cells. From Athens to Atlanta, the state is rapidly becoming a center for the high-tech innovation known as bioscience. This broad term includes everything from new medical therapies created by harnessing cellular and biomolecular processes to biodegradable alternatives to plastic.

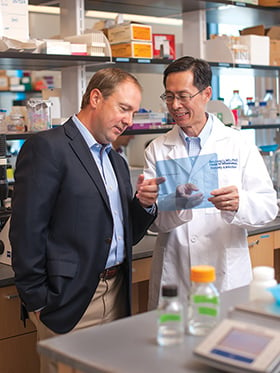

Earlier this year, Atlanta hosted the annual Business of Regenerative Medicine conference. This gathering of leading researchers and dealmakers was here largely because Georgia Tech’s Parker H. Petit Institute for Bioengineering and Bioscience has quietly become the nation’s leader in regenerative medicine, a form of tissue engineering and molecular biology that tries to replace or regenerate human cells, tissues or organs to restore or establish normal function.

Since 2008, the Petit Institute has been bringing together scientists and engineers from different academic disciplines to tackle the complex problems of human disease.

“Regenerative medicine is taking off like gangbusters now with big companies coming into the field and making large investments in these therapies,” says Dr. Robert Guldberg, executive director of the Petit Institute.

The conference draws scientists from around the world to discuss breakthroughs, pick up tips on how to get funding and listen to announcements of company formations.

It’s that last part – the new businesses – that is increasingly on display. Research in Georgia labs is leading to products administered to real live patients.

“This is recognizing that we can’t just do science,” says Guldberg, who is also a researcher specializing in musculoskeletal growth and development, functional regeneration following traumatic injury and degenerative diseases like osteoarthritis. “We can’t just work in the lab to get [it] into patients; we need to get it out and commercialized.”

The bioscience field in general – and research universities like Georgia Tech in particular – is a growing source for startup companies that are becoming successful and profitable.

“When I first came here 20 years ago, if you asked a group of faculty who [among them] had a startup company, there would be maybe a handful,” he says. “Now I would say [that] probably 60 to 70 percent of faculty have some sort of startup company. That’s in part because Georgia is a good place to do startups. It’s also recognizing that unless we pay attention early on, there’s very little chance these [advancements] will get to patients.”

Roaring Ahead

In recent years, Georgia has provided fertile soil to grow bioscience companies. It holds the promise of not just creating remarkable advances in the treatment of disease and answers for other problems, but it is also fast becoming a powerful job generator.

In fact, healthcare and information technology are the two fastest-growing sectors of the Georgia economy, according to a state labor department report on workforce trends for the year 2020. It’s not surprising that the fastest-growing occupation – biomedical engineering – combines the two.

The biotech field can encompass anything from nanotechnology and new imaging technology to wearable devices, “all of these things you can think of as a technology-intensive approach to medicine as opposed to a small molecule where you make a pill to swallow,” explains Ravi Bellamkonda, who chairs the Wallace Coulter Biomedical Engineering Department at Georgia Tech.

Biotechnology is attracting a lot of attention as the population ages and healthcare becomes a bigger part of the national economy – roughly 17 percent of GDP.

Georgia is currently home to 433 bioscience companies, primarily located in Atlanta, Augusta and Athens.

“I’m seeing quite a bit of support infrastructure building specifically here in Georgia just in the last year or so,” says Russell Allen, president and CEO of Georgia Bio, a nonprofit organization that promotes the life-sciences industry. “We’ve seen new accelerators to support the industry. Funding has been stellar this year for our members. And I think the interest in the development area on the real estate side is starting to pick up as well.”

From Startups to Corporations

There are numerous bioscience-related institutes and initiatives at Georgia’s universities, many of which are clustered in Atlanta, including Emory and its 11 affiliated institutes, Morehouse School of Medicine’s Cardiovascular Research Institute, Clark Atlanta University’s Center for Cancer Research and Therapeutic Development, and the recently launched Institute for Biomedical Sciences at Georgia State University. Plus, there’s Augusta University (formerly Georgia Regents University), which has 12 institutes, including the Institute for Regenerative and Reparative Medicine.

All of these are conducting research related to the bioscience field, and several universities have developed business incubators specifically geared toward the bioscience field to help students and faculty launch businesses surrounding their high-tech innovations.

In Athens, there’s the Innovation Gateway, which helps University of Georgia researchers move their concepts and breakthroughs into the marketplace through licensing and startups. And in Atlanta, there’s Georgia Tech’s VentureLab. VentureLab not only helps student and faculty startups with their business models, it also assists in finding grant funding, office space and even mentors.

Mark Prausnitz is one Georgia Tech-based academic who has seen his research make it into the marketplace thanks to VentureLab. He co-founded Clearside Biomedical after a multiyear collaboration between Georgia Tech and Emory University School of Medicine that resulted in a microinjection platform to supply drugs into a hard-to-reach section of the eye. These intraocular microneedles deliver drugs directly to the back of the eye less invasively than other types of injections. The approach uses lower amounts of the drug than topical or periocular approaches and reduces side effects by minimizing off-target drug exposure.

Clearside Biomedical was established through a $12-million investment from Hatteras Venture Partners, Georgia Research Alliance Venture Fund and Kenan Flagler Venture Fund in January 2012. Although not yet profitable, the company has moved rapidly forward toward developing products for the market – far beyond what could be achieved within a university environment – thanks to VentureLab.

The company is just one of more than 300 startups launched through the business incubator, which has helped attract more than $1.1 billion in outside capital. In fact, the group has been ranked as the No. 2 incubator in the country.

These startups have the potential to revolutionize how we treat patients and deliver medicine around the world. Prausnitz, for example, has also developed a patch covered in microneedles that painlessly injects medicine just below the hair-thin outer layer of the skin. The needles themselves dissolve, eliminating the risk of disposing of used needles.

Funding of clinical trials for the patch has come from the federal government and the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation. These patches could not only make it easier to administer vaccines to at-risk groups, but also cut costs by eliminating the need for an injection to be given by a healthcare professional.

Prausnitz says the Gates Foundation wants to use the patches for vaccination campaigns in developing nations where trained healthcare workers are scarce.

To further development of the device, he and two other colleagues formed a company called Micron Biomedical, and they are in the process of licensing the technology out of Georgia Tech not only for delivering flu and polio vaccines, but also for other vaccines and drugs.

One of the critical issues facing universities is whether this research should be licensed to a big company for development or the researchers themselves build a company around it.

“Companies are not just technology,” says Prausnitz. “They’re also people, and people are critical to the success of the company. Is the inventor the kind of person who will be good at starting a company and participating at some level? Are there others you can attract with not only technical expertise, but the business expertise to build a team that’s going to do the job well?”

There’s also a new breed of business accelerators that work virtually and is typically aimed at helping later-stage startups.

“They provide mentoring services and guidance for everything from business plans to their pitch to their management and operations and usually a little bit of funding to help them get things moving forward,” Allen says.

These include NeuroLaunch, which bills itself as the world’s first startup accelerator program for neuroscience companies, and Emergence, which provides services to healthcare IT, medical devices and other related startups.

While there are hundreds of such startups launching across the state, biotech in Georgia is more than the small businesses. It also includes some very large companies with big operations. A reflection of just how diverse the field is can be found in the fact that one of the largest subsections – healthcare IT – is bigger here than anywhere else in the country. In fact, the state has more than 200 of these companies employing more than 15,000 workers, with the majority homegrown.

Baxalta Inc. – which was formerly part of Baxter International Inc. – is constructing a $1-billion biopharmaceutical plant in Covington to support global growth of its plasma-based treatments for immune disorders, trauma and other conditions. The plant will employ more than 1,500 workers once it is completed in 2016 and fully operational in early 2018.

Other companies, like QualTex Laboratories and ADMA Biologics in Norcross, Dicon Technologies Inc. in Moultrie and Reliant Medical Services in Thomson, have all moved operations to Georgia over the last decade. And companies like MiMedx, which is located in Marietta, are expanding to keep up with demand. The company manufactures regenerative biomaterials and bioimplants for wounds and burns that are typically used in surgery and sports medicine.

Seeking Investments

Doing research and turning that research into a product and a company takes money. Getting that money can be difficult no matter how promising the device or the procedure may be. Chastened by the collapse of the tech boom and the Great Recession, venture capital funds rarely invest in early-stage companies. Today, they’re looking for companies with a track record and generally want to get involved only after clinical trials have proven that a great idea works in practice.

“I’d say for our industry that the vast majority of our medical innovation companies have university roots,” says Allen. “So the universities are initiating development. They’re developing ideas into companies, and then those companies are going on to succeed through partnerships and raising capital and bringing their products to market. But they still maintain that university connection, and the universities provide great resources for the industry itself. So those partnerships become important in R&D, sometimes in manufacturing and certainly in clinical trials.”

As a result, funds come from federal agencies such as the National Institutes of Health or from local agencies such as the Georgia Research Alliance, which has its own venture capital fund.

More recently, Georgia Bio organized BioMed Investor Network, an alliance of angel investors. While the number of angel investment groups in the state is growing, few specialize in healthcare and bioscience.

“We have over 50 investors in the network, and we did that in just about three months,” says Allen, adding that they have already started investing in companies. “We’re communicating very well with the venture community in helping to build a pipeline for their later-stage investments. So the venture funds may not invest directly in early stage, but they’re paying attention and they’re participating with angel groups and perhaps helping fund them. There’s a fund model out there wherein the venture capitalists put in a portion as a limited partner that is designed to invest in early stage. So it helps them build that pipeline and have something to invest in down the road.”

“The payout for a therapeutic, especially a stem cell therapeutic, is beyond many of the VC’s horizons as far as when they want to get their money back and their multiples payment back,” says Dr. Steven Stice, a University of Georgia researcher in regenerative medicine who founded ArunA Biomedical.

Regenerative medicine firms have gotten support from international sources such as Japanese pharmaceutical firms that are willing to wait longer for a payout and can better tolerate the speculative nature of early clinical trials, according to Dr. Reni Benjamin, senior biotechnology analyst with Raymond James & Associates.

He notes that these companies “are not necessarily looking for an immediate return on their investment in terms of stock. They’re making bets on products and the potential of those products making it to market.”

Attendees at the Regenerative Medicine conference also heard about a different approach to driving companies with the announcement that Medtown Ventures has launched CellectCell Inc.

Medtown specializes in the capitalization and commercialization of promising life science companies. The company isn’t a traditional venture firm; instead of only investing in companies, it operates them with its own management personnel.

“I like early stage and cultivating that idea, but it does require a lot of investment, so a lot of venture groups have left that,” says Chris Fair, managing director and founder of Medtown Ventures. “Most venture groups are a fund without a team. I’m a team without a fund. If we need to raise outside money, we have enough folks who will bet on the jockey rather than the horse. So there are people still investing, but they’re only investing in teams over technologies. That’s really what the challenge is at the university level. They don’t have the team – they only have the technology.”

Medtown entered into an exclusive license agreement with Georgia Tech Research Corp. for a new adhesive-signature based stem cell selection and isolation technology. The μSHEAR technology can isolate populations of cells with greater than 95 percent purity in less than five minutes.

It formed the new company with the inventors to focus on the commercialization of the technology. The license agreement allows CellectCell to develop, manufacture, use and sell products containing the technology.

“The life science investors are still there,” observes Fair. “They’re fewer, but they want to see a more revenue-based plan versus ‘hey, look at this great technology.’ The marketplace has changed. Reimbursement has changed. Now derisking the business is the only pathway to get to an acquisition. Most acquirers are saying ‘I’m not going to buy you when you’re a patent. Go through the effort to become a company, and then I’ll buy you.’”

Despite the promise of this area of bioscience, it has to produce a blockbuster drug, according to Benjamin.

“Now some people may take offense to that statement and say here’s this bone marrow based treatment that is on the market, and it’s generating $50 to $100 million a year,” he explains. “That’s not the true potential or the blockbuster indications to highlight the potential for regenerative medicine. The potential to take stem cells and cure Alzheimer’s, cure stroke or some sort of cardiovascular congestive heart failure – those are the big ticket items.”

While some areas of bioscience have been slow to reveal their full financial potential, many products, drugs and therapies lie just around the corner. These include immunological vaccines such as those being produced at Emory University’s vaccine center. Treatments for dreaded infections such as Ebola, forms of cancer or autoimmune diseases are also being developed, according to Bellamkonda.

These new developments will mean both jobs and investment for Georgia and a better life for people everywhere.