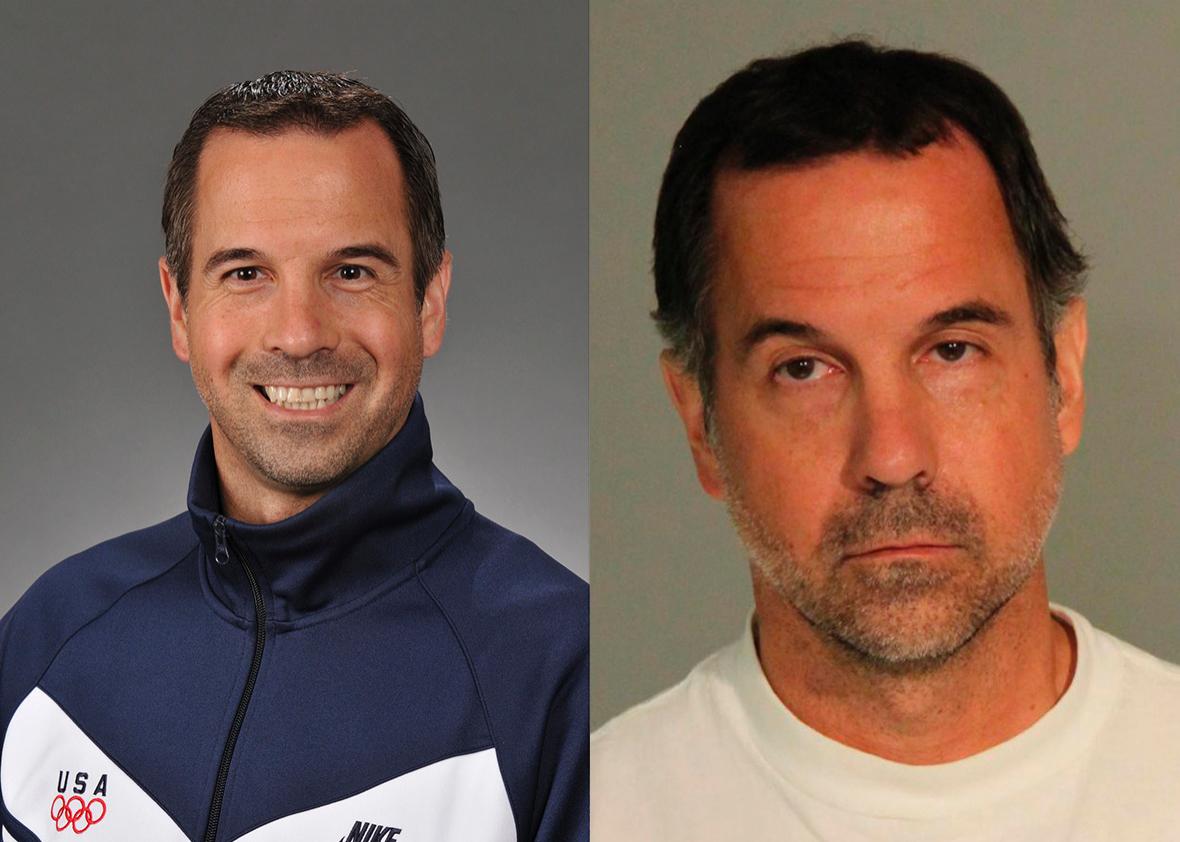

This past Saturday, Indianapolis gymnastics coach Marvin Sharp—who once mentored Olympians Bridget Sloan and Samantha Peszek—was found dead in his Marion County, Indiana, jail cell in an apparent suicide. Sharp had been arrested Aug. 25 on one count of child molestation and was subsequently charged, at the state and federal level, with sexual misconduct with a minor and possession of child pornography. He was 49.

The accusations against him were stomach-turning. One of the gymnasts at his academy alleged that over the course of two years, he compelled her to pose for hundreds (“if not thousands”) of photographs that any reasonable person would infer to be lurid and that he touched her inappropriately during the “shoots” and while assuming the role of de facto physical therapist. According to investigators, the staggering amount of child pornography recovered from Sharp’s residence betrayed a monstrous reality lurking behind the star-studded exterior of his gymnastics dynasty.

I cannot begin to wrap my mind around why someone would do the things that Sharp is alleged to have done. But I can tell you exactly how a person in his position could commit such acts under the unsuspecting noses of teammates, parents, and other coaches—and get away with it for years.

I knew Marvin Sharp. He was my gymnastics coach. Before he took Sloan and Peszek to the Olympics, before Sharp’s Gymnastics Academy became a destination gym, he coached Levels 6 through 10 at the National Academy of Artistic Gymnastics in Eugene, Oregon. He didn’t produce any Olympians back then as a mustachioed 23-year-old. But he did take me and my Level 6 teammates to the state championships, where my best friend won her age division and I placed 10th on the floor exercise.

Coach Marvin was arrogant and vain. (He drove a cherry-red Jeep with the vanity plate SHARP.) He was also near-magical in his ability to coax difficult new tricks out of even the less talented among us (like me). It was heartbreaking when he decided to hand-pick the five tiniest and most talented girls to create a special new Level 6 group, a “pre-elite” program run under his exclusive tutelage. I was mad with jealousy—back then, I would have given anything to be as minuscule, as formidably gifted, as adored as his preteen favorite, who spent so much time spent nestled into his lap.

There are intrinsic aspects of competitive gymnastics that are absent in almost every other sport, and that could not be more welcoming to potential pedophiles. Of course, the vast majority of gymnastics coaches are not child molesters or pornographers. But a sickening number have been accused, arrested or convicted of such offenses just in the past five years alone—Sharp wasn’t even the first who’d coached me to get in legal trouble. He was the third.

It’s not just the unfettered access to young, barely clothed athletes, although obviously that’s a part of it. Gymnastics also requires an intense mixture of physicality and trust. A girl training a new trick—a full-twisting back handspring on beam, a breathtaking series of release moves on bars, a potentially deadly Yurchenko-approach vault—is life-dependent on her coach handling her body. An outsider might be shocked at the level of bodily contact between coach and athlete and at how blasé the gymnast is about being pawed. What’s more, the coach doing the pawing is almost always male—women often lack the height or upper-body strength to spot difficult skills.

There is also the potentially infinite amount of time an athlete can spend alone with her coach with zero questions asked. Extra practice on a Saturday afternoon? For a high-level athlete training for a big meet, not weird at all. A late-night ride home from a meet in another town? Happened to me more times than I can count. Travel with only the coach as the chaperone? I remember being so envious when Coach Marvin’s special group got to fly all the way to Hawaii with him.

Finally, competitive gymnastics is so time-intensive—training five to eight hours per day, plus meets on weekends—that the coach often assumes an intensely paternal role. I wasn’t even an elite-level athlete, but during the years I spent as a gymnast, I sometimes interacted more with my coaches than I did with my own parents. And I cared more when Coach approved and cried more when he bawled me out in the training room (always alone, it goes without saying).

Some of you may be asking yourselves: Why did Sharp’s alleged victim cooperate with these grotesque photo shoots for two entire years? Notwithstanding the fact that the victim was just 12 to 14 years old, anyone with experience in competitive gymnastics would tell you that coaches favor the tiny and perfect, yes, but also the docile and obedient. Say “no” to Coach, and you may discover you’re suddenly not on the roster for the Great Western Invitational in Reno.

After Sharp left my Eugene academy under circumstances that were never made clear (but did not involve, as far as I know, criminal activity), I once ran into him at the movies. He was with three girls who couldn’t have been older than 12. I’m sure their parents—like the delighted mothers and fathers of the “pre-elite” girls, excited their offspring might just be headed for Seoul or Barcelona—sent them off happily, knowing how talented and special they must be to garner Coach Marvin’s favor. What other sport would grant a 24-year-old man the pretense to go out to the movies alone with a gaggle of preteens?

Sharp apparently died by suicide on Sept. 19, which also happened to be National Gymnastics Day. I’m sure the sport’s American governing body did not expect to be celebrating by releasing the following statement: “USA Gymnastics is aware of the untimely death of Marvin Sharp. Our thoughts and prayers are with the families of all involved in this tragic set of circumstances.”

The allegations against Sharp and his death cast a pall over a sport that certainly has plenty of other problems: bodies irreparably broken before they even finish puberty, eating disorders, etc. But gymnastics is also unparalleled in its combination of superhuman athleticism and balletic grace. I love gymnastics, I always will, and I eagerly await the 2016 Olympics.

But I worry that one or more of the new hordes of starry-eyed little girls who descend upon gyms in the games’ wake—as I did after beholding Mary Lou Retton in 1984—will once again find themselves in situations that provide the easiest possible means and opportunities to be harmed. All that’s missing is the motive. Sharp’s case is a stark reminder that motive could be lurking anywhere—even behind the smiling eyes of a champion-maker.