- India

- International

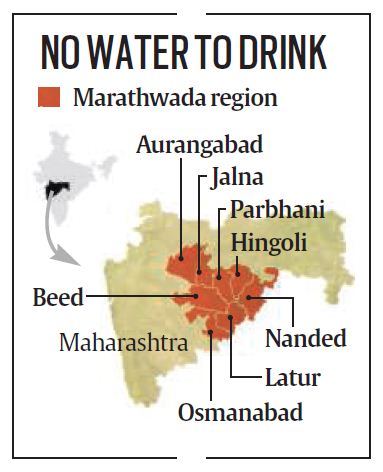

Failed crops, parched fields, now Marathwada faces the great thirst

Wells dry up across 8 districts, storage down to less than 8%, residents trudge long distances, officials brace for worst drinking water crisis in 40 years.

In a field in Beed, women work despite falling wages so that their earnings can help pay for water tankers. (express Photo by: Kavitha Iyer)

In a field in Beed, women work despite falling wages so that their earnings can help pay for water tankers. (express Photo by: Kavitha Iyer)

Seventy-year-old Parobai Shinde, carrying an aluminium pot that has seen better days, is briskly walking the 2-km stretch from her home in Manyarwadi village in Georai taluka in Beed district to Bharat Sonmali’s field. Sonmali is reploughing his 30 acres, the cotton and soyabean he had sown having withered after a 50-day dry spell that saw barely 90 mm of rain in Georai until August 28. But his field is one of the few that has a well which has water and that’s where Parobai is headed. There’s no water at home — but then there’s no cash either.

So Parobai keeps the pot aside, begins a day of labour at the field across from Sonmali’s — where work is available at daily wages that are down from Rs 100 to Rs 60.

Her story is replicated across the parched Marathwada region, comprising eight districts, hit by a 50 per cent deficit in rainfall. Even with a month to go before the monsoon withdraws, the state government is considering declaring talukas with a rainfall deficit of over 50 per cent as drought-hit. As of August 28, the total average rainfall received across the eight districts was 252.42 mm, with four districts receiving less than 50 per cent of average rainfall for this time of the year.

Her story is replicated across the parched Marathwada region, comprising eight districts, hit by a 50 per cent deficit in rainfall. Even with a month to go before the monsoon withdraws, the state government is considering declaring talukas with a rainfall deficit of over 50 per cent as drought-hit. As of August 28, the total average rainfall received across the eight districts was 252.42 mm, with four districts receiving less than 50 per cent of average rainfall for this time of the year.

[related-post]

Simultaneously, across the worst-hit regions of Beed, Parbhani and Osmanabad, the refrain in households and on barren farmland is that this drought could emerge worse than the worst witnessed to date. “The 1972 drought was one of foodgrain,” says Limbaji Mogar, owner of 60 acres in Parbhani’s Nagthana village in Selu taluka. “This time, there’s plenty of foodgrain but no money to buy, no water to drink even if we sell our gold to buy it, right in the middle of what you call a monsoon season.”

The analogy is almost literal.

In neighbouring Chikalthana village, small farmer Vishnu Korde says 80 per cent of villagers have gold loans besides crop loans and dues to private moneylenders. “Some of it was auctioned off for defaulting on payments,” says Korde. “Water is not just an essential commodity for us — how thirsty we are defines our earning capacity, our animals’ longevity, and therefore, our assets, our economic growth or rising debt.” Villagers in Selu and neighbouring Jintur talukas describe paying Rs 10 to Rs 15 for three pots of water from private water-tankers, and that is only for household use.

Those with large animal broods must spend long hours walking weary cattle to drinking-water sources. Fodder and water are to be made available at cattle camps with the state government having sanctioned funds for camps in three districts Osmanabad, Latur and Beed. Parbhani’s precarious position has led to the Divisional Commissioner’s office making a request for camps in Parbhani, too, but ten days on, none of these is operational.

About 160 km away in Aurangabad, as officials compute scarcity norms of per-person-per-day thirst, Manyarwadi or Chikalthana hardly register as a blip. The big challenge right now is Latur, teetering on the brink of a crisis — water stock that will run out completely on September 15 if rains do not oblige. Manjara dam, “Latur’s lifeline” as Divisional Commissioner Umakant Dangat describes it, has run completely dry. Nearby Majalgaon dam is hardly any better.

Latur’s drinking water problem isn’t simple. Marathwada’s other big city Aurangabad is reassured by the Jayakwadi dam’s 5 per cent live storage but Latur’s 5 lakh people pose a challenge. Central Railway General Manager Sunil Sood tells The Indian Express that the Railways is preparing itself, steam-washing four oil wagons that will be used to transport water. The idea is to pick up water from Ujani dam, risking upsetting political heavyweights in Solapur district which depends on this dam across the Bhima with a current stock of 58 tmc (thousand million cubic feet). But supply by railway wagons has its problems: where to park while wagons are emptied, how to navigate an unprecedented number of tankers through Latur railway station’s rudimentary infrastructure. According to Dangat, other options are being studied, including that of taking water from an NTPC pipeline running through Kurduwadi, a major train junction 150 km from Latur.

According to data from the government, the 833 small, medium and large dam projects in Marathwada together have just 7.8 per cent of water storage as of August 28, compared to 22.76 per cent on the same date last year.

Naturally, drinking water in the other municipal areas of Marathwada is also no more than a steady trickle once every eight to 10 days, sometimes once in 15 days, the remainder of the demand met by borewells. Prasad Chikshe of Ambejogai in Beed, an IIT graduate and scientist with the Gnyana Prabodhini, says Beed district alone has almost 100,000 borewells, and these are just those recorded by the government’s agriculture officers. “The real number, including those in urban areas like Ambejogai, may be five times as many,” he says.

A neighbour has dug a borewell almost 500 feet deep only a few days back, he says, and farmers as well as urban households are going to increasing, unsustainable depths for water in the absence of any community water management efforts.

Meanwhile, in Sarnisangvi village of Beed district’s Kaij taluka, Marathi and social sciences teacher Uddhav Gholve is completing his math for the coming month’s expenses. The farmer with five acres, MA and B Ed degrees hasn’t visited his fields for 25 days now, knowing the cotton and soyabean have dried up. Times are tough at home, but Gholve and about 25 other teachers at the Srivithal Secondary School and Junior College in the village are contributing for private tankers for the school, to ensure that dropout rates don’t surge even if it means an expense of Rs 10,000 every month.

At home, wife Suvarna does the tightrope walk between rationing water for the two children, for guests, for the animals, ensuring not a drop is wasted. “Having a salary is a buffer, so I can afford to pay for water perhaps,” Gholve says. “But farmers who have nothing to soften the blow of consecutive failed crops over four or five seasons can certainly not afford to buy water.”

The school, like most, has a well that has run dry. Gholve says primary health centres and rural hospitals are all crippled by water scarcity. From maintaining hygiene to providing sufficient drinking water, rural hospital nurses and doctors in Marathwada are almost entirely dependent on borewells and tankers.

Back in Manyarwadi, Parobai collects her Rs 60 at the end of the day and heads home, after a pit-stop at the farm well. No food was cooked at home today, her son and his family also out looking for work. “This has been one long summer,” says the 70-year-old. “Longer than any I remember.” Thirst is making it longer.

Apr 16: Latest News

- 01

- 02

- 03

- 04

- 05