- India

- International

The quality of mercy: Restorative justice has started to make its impact in India

What does it take to forgive someone who has done a grievous harm? And does it really help one forget? Even though the idea of restorative justice is yet to find a firm foothold in India, those who have experienced it say the act is twice blessed.

Restorative justice, where criminals either meet their victims or are forgiven by them, may still be a rarity in India as compared to the West, but it has slowly started to make an impact. (Source: Thinkstock Images)

Restorative justice, where criminals either meet their victims or are forgiven by them, may still be a rarity in India as compared to the West, but it has slowly started to make an impact. (Source: Thinkstock Images)

If anyone had asked six-year-old Avantika Maken what she wanted to do when she grew up, it would had taken the little girl an instant to reply: “Kill the person who killed my parents.”

It was a sentiment that festered in her as she grew up, with anger, loneliness and helplessness compounding her immeasurable loss. Her wallet always carried photographs of her parents Lalit Maken, Congress leader and MP and his wife Gitanjali, daughter of former president Shankar Dayal Sharma. Except that these were not happy family photos, but those of their bullet-ridden bodies. In her wardrobe, tucked in a corner was a blood splattered locket — the one her mother had been wearing on that fateful day of July 31, 1985.

She’d been 10 days short of her sixth birthday, when three men waylaid her father, then 35 years old, as he stepped out of their house in west Delhi’s Kirti Nagar.

[related-post]

As the men opened fire, Maken tried running back inside the house. Gitanjali stepped out to shield her husband. A few minutes later, Maken’s mother would reach the spot to find her son dead and her daughter-in-law fatally wounded. Gitanjali would later die in the operation theatre.

Avantika realised something was wrong when someone from her maternal grandfather’s office came to pick her up from school that afternoon. “That day as I was getting ready, my mother scolded me over something and said they would not come to pick me up after school. But my father smiled and said, of course, they would,” says Avantika, now 36 years old. Shankar Dayal Sharma was then the governor of Andhra Pradesh and she was taken to Andhra Bhavan where he broke the news to her.

“He said, ‘Promise me you won’t cry’ and I didn’t,” says Avantika.

After two decades of inner turmoil, Avantika finally found peace after she forgave her parents’ assassin (Source: Express photo by Oinam Anand)

After two decades of inner turmoil, Avantika finally found peace after she forgave her parents’ assassin (Source: Express photo by Oinam Anand)

But the loss left her ravaged. “I missed my parents, especially my father. Initially, both sets of grandparents went to court to get custody of me, but by the time the judgment came, they all agreed that I would be better off in a hostel. That made me feel unwanted. I didn’t have any siblings to turn to or a home of my own. I was studying in Modern School in Delhi when my parents died. Afterwards, I was sent to Maharani Gayatri Devi hostel in Jaipur and then to Welham in Dehradun. At 18, I opted to get married just so I could stop living in relatives’ homes. But the marriage didn’t last. I feel a lot of my personality was shaped by the loneliness and the insecurities of my childhood,” she says. Avantika is now married to Haryana Congress MP Ashok Tanwar and the couple have three children.

The three men who had murdered her parents were eventually caught. Ranjit Gill aka Kuki, Harjinder Singh Jinda, Sukhdev Singh Sukha were extremists out to avenge the 1984 violence against the Sikh community after the assassination of prime minister Indira Gandhi. Lalit Maken’s name had figured in a 31-page booklet released by the People’s Union for Civil Liberties called “Who are the Guilty?” that had names of Congress leaders involved in the carnage in Delhi’s colonies. Sukha was arrested in 1986 and Jinda in 1987 — both were later sentenced to death for the murder of General Arun Vaidya, architect of Operation Bluestar and hanged in 1992.

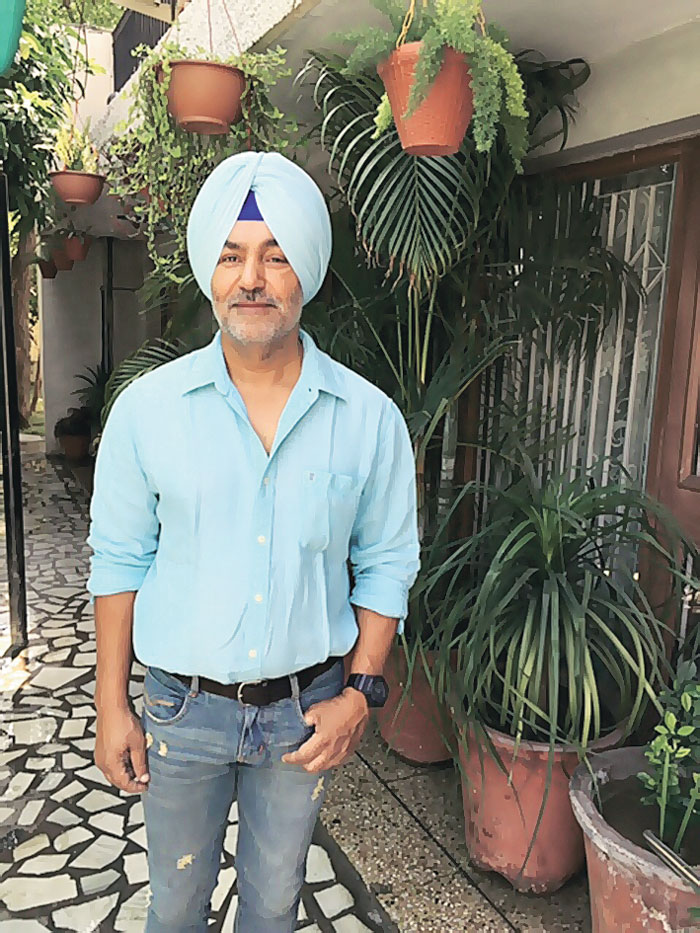

Kuki says he now realises that violence is never the right response to any injustice

Kuki says he now realises that violence is never the right response to any injustice

Meanwhile, Kuki fled to the US and was arrested by Interpol in New Jersey, USA in 1987. He was deported to India in February 2000 and sentenced to life imprisonment in 2003. Later that year, a petition was filed asking that his life sentence be commuted on the ground that the fatal shots hadn’t been fired by him. But it hinged on Avantika’s consent.

The volcano of bitterness that had been building up in Avantika finally found its vent in 2008, but in a manner no one quite expected. That year, Avantika met the then Delhi chief minister Sheila Dikshit and asked her to agree to the petition that had been moved. She then went to Kuki’s house and had a meal with his father.

As Kuki’s sentence in prison ended and he was set free, it was Avantika who finally found a release.

Restorative justice, where criminals either meet their victims or are forgiven by them, may still be a rarity in India as compared to the West, but it has slowly started to make an impact. Much of its importance lies in the fact that what it unarguably does is to facilitate the most difficult task of any tragedy — bring a closure to a painful chapter in one’s life. It was what Priyanka Vadra Gandhi had admittedly sought when she travelled to Tamil Nadu in 2008 to meet Nalini Sriharan lodged in Vellore jail for her complicity in the assassination of her father, former prime minister Rajiv Gandhi. It was also what made Gladys Staines, widow of the Australian missionary Graham Staines, publicly forgive the man who burnt to death her husband and two sons in Orissa in 1999. And it was what Avantika received in return for her generosity of heart and spirit.

“My father was my hero — he was good-looking, charming and sang well. But he was also a victim of politics,” she says.

HS Phoolka, senior advocate of Delhi High Court, human rights activist and author, known for spearheading one of the longest and torturous legal battles to gain justice for the victims of the 1984 anti-Sikh riots and fighting individual cases on the involvement of politicians in the riots, says little is known about the nature of Maken’s involvement in the anti-Sikh riots. “I have no first hand evidence of his involvement other than having read his name in the report,” says Phoolka.

Avantika had other unanswered questions too: Was Gill the one who pulled the trigger? What were her parents’ last thoughts? When Kuki’s petition came up, Avantika had been in Ludhiana campaigning for her colleague Manish Tiwari for the upcoming Lok Sabha elections. “There was a journalist who knew both Kuki and me. She asked me if I would be open to meeting him,” says Avantika. Her anger hadn’t subsided, but she agreed to meet him so she could hear his version of the accounts of that day.

The meeting took place in Ludhiana in May 2004. “I told her that it was a political fallout, that I had certainly been involved in the conspiracy, but I wasn’t the one who had pulled the trigger that killed her parents. She asked me, why my parents? I told her that her father’s name had been on that list, but her mother’s death was an accident. She came in front of her father during the firing and that I was deeply sorry about it. Looking back now, I realise that violence is a shortcut and not the proper way to express resentment at an injustice,” says Kuki, 55, who now lives in Ludhiana with his wife and daughter and writes a weekly blog navjawani.com.

That meeting changed things for Avantika. Kuki had been a gold medallist at the Punjab Agricultural University at Ludhiana, where he had studied genetics and crop science. His incarceration had not been easy for him either. “Kuki came across as a well-educated, soft-spoken person. I went to his house and met his parents and suddenly, images of how I had seen my grandparents pine for their son and daughter and cry all the time flashed before my eyes. I realised I didn’t want another family to go through the same pain,” she says. She was moved by the anguish of Kuki’s parents. “My maternal grandparents, the Dayals, were in politics, so they still had their public life to hold them together. My paternal grandparents were especially devastated because they were a middle-class family whose lives revolved around their children,” she says.

Her decision, when it came, didn’t take long. “I thought he had suffered enough. Our jails are worse than death. You die every day there instead of that one day, and I wasn’t sure his death would make things better for me. My loss could never be replaced, but if, because of me, another family’s loss could be stemmed, I felt I needed to take the step,” she says. Her family, all except her eldest son, supported her decision. “What is the point of holding on to a grudge if it gave me no peace? Now I can finally say I am happy. I have my own home and family and am at peace with myself,” she says.

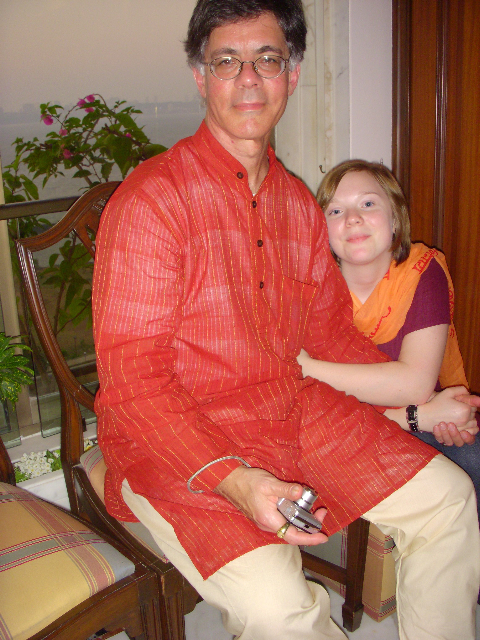

Alan, Naomi in Mumbai

Alan, Naomi in Mumbai

But if it took Avantika 23 years to arrive at forgiveness that took away the searing pain she had nursed till then, for American national Kia Scherr, the move was almost instantaneous. In November 2008, Kia’s husband Alan and their 13-year-old daughter Naomi were shot dead in Mumbai’s Oberoi hotel during the terror attack of 26/11. Kia was at that time in Florida spending the Thanksgiving weekend with her parents; she had dropped out of the trip at the last minute. As she sat with her family watching the aftermath of the attack on television, she saw the grainy image of the lone terrorist who had survived — Ajmal Kasab — flashing across the screen . She was numb with sorrow, but remembers that her first reaction was to turn to her family and say, “We must forgive them.” Scherr counts that among the most difficult moment of her life. “Despite the shock and outrage, the moment I uttered those words out loud, I felt a ray of peace,” says the woman who became a life skills teacher afterwards with the organisation she founded, One Life Alliance, that teaches people love and tolerance.

Alan and Kia

Alan and Kia

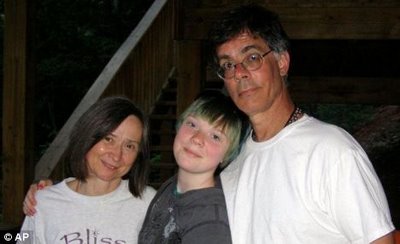

Alan, Kia and Naomi during their vacation

Alan, Kia and Naomi during their vacation

While their meeting gave both Avantika and Kuki a sense of closure, for Kia, seeing Kasab on screen meant the beginning of a whole new journey. “I knew that if I could forgive the terrorists, I could go on living and loving. There is already enough hate,” says Kia. She even wrote a letter to Kasab in 2012, but it remained undelivered.

Kia says her decision to forgive was prompted as much by her religion as that of her faith in a modern spiritual organisation Synchronicity, of which she and her husband had been members. Synchronicity uses technology to promote a message of oneness and sacredness of life around the world. In fact, it had organised that trip to India in 2008 to spread the foundation’s message. “Forgiveness serves to free us from holding on to hatred, resentment, anger and feelings of revenge. This does not mean any of us pardon those actions or condone in any way what they (the terrorists) have done. We all agree that actions have consequences and the law of the land must be upheld,” says the 59-year-old, who comes to India regularly and visits the Oberoi hotel, the place where she lost her family.

Anup Surendranath, director at the Centre of the Death Penalty at National Law University, New Delhi, and one of the most vocal anti-death penalty crusaders in the country, says that while everyone has their own moral and philosophical stance on capital punishment, there needs to be a debate on two other fronts. “One is that given our political and economic realities, whether we as a country are in a position to administer the death penalty in a fair and constitutional manner. And the second is the idea of forgiveness and compassion. It’s very surprising that in a society like ours, this idea has not taken off the way it should have. There is a strong cultural ethos for this debate to take place. A very strong marker or indicator of the way a society has evolved is how it treats its prisoners or those condemned by that society. Forgiveness and empathy need to be an integral part of our criminal justice system. The whole idea of reformation is sorely missing,” says Surendranathan.

Sometimes, forgiveness can indeed set one on the path of reformation. On February 25, 1995, Rani Maria, a Roman Catholic nun, was travelling from Udainagar to Indore in Madhya Pradesh, by bus when she was attacked. Samundar Singh stabbed her 54 times and dragged her body out of the bus. A trial court sentenced Singh, then aged 22, to life imprisonment. At prison, Singh met Michael Purattukara, a Catholic priest who visited inmates. Purattukara, now known as Swami Sadanand, is the founder of Sachidanadan Ashram in Narasinghpur in Madhya Pradesh. He began counselling Singh. “In the beginning, Singh was unrepentant and wanted to take revenge on the person who had hired him to kill Maria. He told Sadanand that he had been paid Rs 10,000 by a local leader. After realising that Singh had been used as a pawn, the priest began working for his release,” says Stephen, Maria’s elder brother.

Samundar Singh with the parents of Rani Maria, the Catholic nun he had stabbed to death

Samundar Singh with the parents of Rani Maria, the Catholic nun he had stabbed to death

Sadanand informed the nun’s family in Kerala about Singh’s role in the crime, and they were willing to forgive him. Maria’s younger sister Selmi, also a nun working in Indore, met Singh in jail. “She met him in the eighth year of his term. She tied a rakhi on his wrist as a mark of accepting him as her brother. In the next two years, she visited him several times,” says Stephen.

After 11 years and six months, the Madhya Pradesh government accepted his mercy plea which had been endorsed by Maria’s family, and Singh was released on grounds of good conduct. But there was no home to return to — his family and wife had abandoned him after he was convicted and his only son had died while he was in prison.

In April, 2012, Sadanand took Singh to Kerala to meet Maria’s parents. His friends in Udainagar warned him not to go; but Singh decided to go to Pulluvazhy anyway. “My father was bed-ridden at the time. Singh came home and threw himself at my parents’ feet, seeking forgiveness for his crime,” recalls Stephen. In a remarkable act of kindness, Maria’s mother, 88-year-old Vattalil Eliswa told Singh that the family was accepting him as member of the family and a third son.

Today, Singh is a farmer and lives in a village 20 km away from Udainagar. His family had left him his share of the land. Every year, on the eve of Maria’s death anniversary, Singh visits her tomb in Udainagar, offering his harvest. He regularly visits the convent where Maria had lived and meets Selmi who works there. In 2013, the story of Singh and Maria’s family was chronicled in a movie titled Heart of a Murderer, directed by Australian-Italian filmmaker Catherine McGilvray. “If the mother and the sister of his victim were able to forgive him and love him as a son and a brother, it means that we too can forgive everything: forgiveness is the ultimate freedom for every human being,” said McGilvray in interviews at the time of the film’s release.

Does forgiveness bring peace? Surendranath says, “When people have suffered the loss of their loved ones, for the longest time they get caught up with the idea that the elimination of the person responsible will bring them a sense of closure. It’s been well documented abroad that when that does happen, it’s very rare that any sense of closure is felt by the victim’s kin. In fact, they are still left grappling with their loss. It’s then that they need to face up to what is it exactly that they had been bottling up or what does closure really entail.”

Five years ago, in September 2010, a fugitive Mujeeb Rahman and his wife Khayarunneesa were found dead inside the forest at Thampuran Estate near Nilambur in Malappuram in Kerala. Rahman had fatally wounded SI Vijayakrishnan of Kalikavu police station two days ago when he had come to his residence at Chokkadu with a police team to execute a warrant issued by a family court on the basis of a complaint filed by his fourth wife. The sub-inspector later succumbed to his injuries and Rahman committed suicide after killing his wife. His two children were sent to an orphanage.

Cut to 2013. At a ceremony held at the school, the two children — Dilshad and Mohsina, 15 and 10 respectively, were gifted a house in the village built by donations from the staff and students of the school. Even more heart arming was the arrival of a special guest at the ceremony — Vishnu, son of the sub-inspector whose father had been killed by Dilshad and Mohsina’s father. It was Vishnu who welcomed the children into the house with the words, “I am here for you as an elder brother, and you are not orphans.” Vishnu, who has also joined the police force, described the gesture more as doing a favour to himself than to anyone else. “I tried to forget the incident, but I couldn’t. Then I decided to forgive the killer and reached out to his children as they were innocent. They had not committed any crime. But they too have suffered like me. Doing that has helped me put my painful past behind me,” he says.

Like it did for Kia. “Forgiveness is the bridge to peace, the bridge to freedom from the past. It simply means acceptance of the reality of the situation and letting go of the incident, which cannot be changed ,” she says.

With inputs by Shaju Philip

Apr 25: Latest News

- 01

- 02

- 03

- 04

- 05