“Main akela chala tha jaanib-e-manzil magar

Log saath aate gaye, karavaan banta gaya.”

(I had started on my journey alone/ But people joined along and we became a caravan)

Majrooh Sultanpuri has so concisely described his journey with this one couplet. His indeed was a passage of a small town boy coming to the city of dreams and growing up to be a legend. From his late ’40s, right to the day he passed away in 2000, he remained one of the most sought after lyricists. The troika of Dilip-Raj-Dev ruled the silver screen and similarly the trinity of lyricists Sahir Ludhianvi-Shailendra-Majrooh was held in high esteem by music directors. All three were poets in their own right, publishing works that remain the canon of Urdu literature. They did films to survive. But they didn’t let lucre dilute the literacy and produced gems, film after film. Their contribution towards the golden age of Hindi film music is immense.

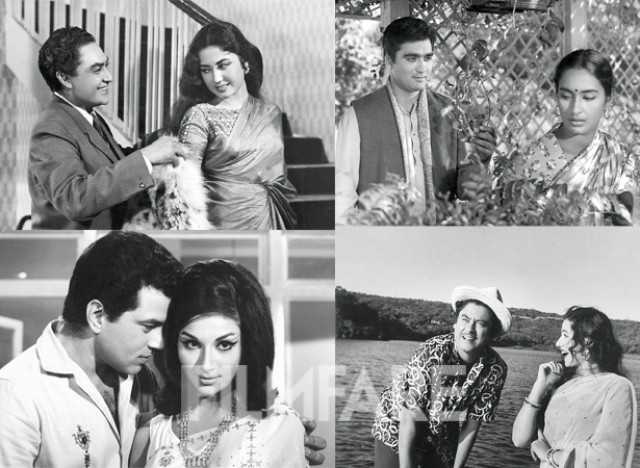

(clockwise) Ashok Kumar and Meena Kumari in Aarti, Nutan and Sunil Dutt in Sujata, Kishore Kumar and Madhubala in Chalti Ka Naam Gaadi and Dharmendra and Sharmila Tagore in Mere Hamdam Mere Dost

Prosaic childhood

Born in an orthodox Muslim family on October1, 1919 in Sultanpur, UP, Majrooh was christened Asrar Ul Hassan Khan. His father, Siraj Ul Hassan Khan was the head constable in the local constabulary. As a result, the young poet had a strict upbringing. It’s believed his father didn’t want him to study English and hence enrolled him at the local madrasa. Watching films or other forms of entertainment were frowned upon.

Rebel poet

Later, the young man was sent to Lucknow to study Unani medicine at the Takmeel-ut-Tib College. This proved to be a blessing in disguise as Persian was a prerequisite for studying Unani medicin. Majrooh, who already knew Arabic, soon mastered Persian as well. The young student soon found access to books on Urdu and Persian poetry and started attending mushairas. He made a place for himself among the literati. Subsequently, he was exposed to the writings of Marx and Lenin. This fascination towards the Left never left him – he remained committed to the cause despite suffering disillusionment later. He had started writing under the nom de plume of Asrar Naseh but after reading Marx and Lenin theories, changed his pen name to Majrooh – which means someone who’s ‘wounded’. He added his birthplace as a suffix.

He passed out as a hakim and was said to have a flourishing practice. This financial independence led him to attend lot more mushairas. Soon, his fame spread nationwide and he started receiving invitations for mushairas all over India. And it was at one such meet held in Mumbai that filmmaker AR Kardar heard him and asked him to write lyrics for his next film. Majrooh initially declined the offer. However, poet Jigar Muradabadi, who had taken him under his wings, advised him to write lyrics as he could then become a full-time poet and wouldn’t have to practise medicine.

Struggle in showbiz

Kardar then urged him to meet Naushad. The composer gave him a tune and told him to write in metre. A few moments later, Majrooh came back with the line Jab usne gesu bikhraye, badal aaye jhoom ke, which was later sung by Shamshad Begum in the film Shahjahan (1946). But it was the KL Saigal rendered numbers Chaah barbad karegi hame maloom na tha and the immortal Jab dil hi toot gaya, which enamoured listeners.

The latter turned into a classic and was liked by Saigal so much that he willed that it be played at his funeral. When the lyricist moved to Mumbai, it’s said, he lived with Naushad for some time. Another version reveals that it was Jaddanbai, Nargis’ mother, who provided him with shelter. Influenced by Faiz Ahmed Faiz, he became part of Progressive Writers’ Movement and started writing openly against the establishment. He, along with Balraj Sahni, was put into Arthur Road jail for their alleged inflammatory writings. They were asked to apologise. Since they refused to do so, they were sentenced to two years of imprisonment.

Ironically, when he was in jail, his songs in Mehboob Khan’s love triangle Andaz (1949), starring Dilip Kumar-Raj Kapoor -Nargis and Shahid Latif’s Arzoo (1950) starring Dilip Kumar-Kamini Kaushal, were creating a stir. It was Raj Kapoor who reached out to the troubled poet at the time. Raj was aware that ‘charity’ would never be accepted by the self-respecting Majrooh.

So the Showman urged him to write a song for him. Majrooh wrote a mukhda, Duniya bananawale kya tere man mein samai, kahe ko duniya banayi, for which Raj Kapoor paid him a handsome token of 1000 rupees. Years later, Hasrat Jaipuri built on that and wrote the antaras for Teesri Kasam (1966).

(clockwise) Zeenat Aman and Vijay Arora in Yaadon Ki Baraat, Sanjeev Kumar and Jaya Bhaduri in Anamika, Aamir and Manisha Koirala in Akele Hum Akele Tum and

Aamir Khan and Ayesha Jhulka in Jo Jeeta Wahi Sikandar

Paradise regained

He had to struggle afresh after his release from jail but thanks to his versatility, soon regained lost ground. He could turn his hand, or better, his pen, to any situation. From sad songs like Hum bekhudi mein tum ko pukare chale gaye – Kala Pani (1958) to a mad cap Paanch rupaiyah barah aana – Chalti Ka Naam Gaadi (1958)

to the even madder C-A-T cat, cat maane billi – Dilli Ka Thug (1958) to the romantic Ab kya misal doon mai tumhare shabab ki – Aarti (1962), he could do it all. From writing for Saigal, he went on to write even for Aamir Khan – Pehla nasha (Jo Jeeta Wahi Sikandar,1992) followed by massy lyrics like Janam samjha karo (Janam Samjha Karo,1999) for Salman Khan.

His songs for Abhimaan (1973) are the best examples of his versatility. All seven songs correlate to a rainbow of moods. Meet na mila re man ka, sung by Kishore Kumar, speaks about a radio star’s need to find the right girl, Teri bindiya re, the duet by Mohammed Rafi-Lata Mangeshkar, is a flirty song between two lovers, Tere mere milan ki yeh raina, the Kishore-Lata duet, is a poignant recital about love lost and found.

Creative highs

He formed associations with most top music directors of the day – Naushad, Madan Mohan, OP Nayyar, Roshan, Laxmikant Pyarelal to Anu Malik and Jatin-Lalit. But his creative synergy with SD Burman and RD Burman stand out. He was at his frothy best with Sachinda, writing fun songs like Chhod do aanchal zamana kya kahega (Paying Guest, 1957), Aaja panchi akela hai (Nau Do Gyrah, 1957), Ek ladki bheegi bhaagi si (Chalti Ka Naam Gaadi, 1958), Hai apna dil toh awara (Solva Saal, 1958), Yeh dil na hota bechara (Jewel Thief, 1967) and many more.

He had a great equation with RD too, particularly in the films of Nasir Hussain, whose prereuisite was only Majrooh would provide the lyrics. RD-Majrooh combinations like Aaja aaja main hoon pyar tera (Teesri Manzil, 1966), Chura liya hai tumne jo dilko (Yaadon Ki Baraat, 1973) and Yeh ladka hai Allah from Hum Kissi Se Kum Nahin (1977) continue to be in demand even today. Majrooh continued his legacy with Nasir’s son Mansoor Khan too in films like Qayamat Se Qayamat Tak (1988) and Jo Jeeta Wohi Sikander (1992). Papa kehte hain or Akele hain to kya gham hai from the former and Yahan ke ham Sikandar or Pehla nasha from the latter are still hummed today.

Awards & rewards

He won his only Filmfare Award for the song Chahunga mein tujhe sham savere from Dosti (1964). He was the first lyricist to have been awarded the Dada Saheb Phalke Award in 1993. He was also the recipient of the Ghalib Award and the Iqbal Prize. He developed pneumonia and died at the age of 80 on May 24, 2000. He may no longer be among us but his immense contribution to poetry, both on and off screen, continue to entertain and inspire millions with each passing year…

SHOW COMMENTS