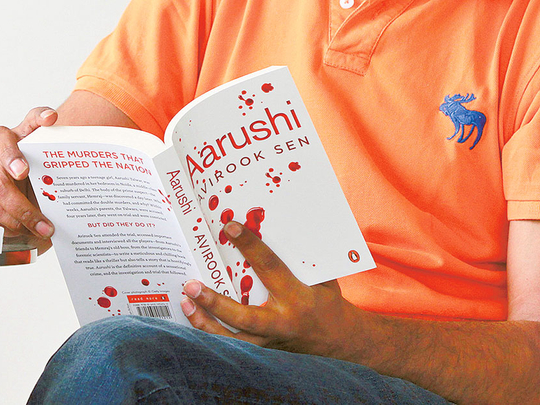

Investigative journalist Avirook Sen’s recently released book, “Aarushi”, delves deep into a sensational murder case of a 13-year-old girl seven years ago that had shocked India. While Sen painstakingly lays bare the details that were always there, he also goes into how the Central Bureau of Investigation (CBI) manipulated and distorted facts and resorted to unethical means to frame the parents of Aarushi, Nupur and Rajesh Talwar for the murder of their only child.

The book also provides an insight into the judiciary and its insensitivity towards the couple who stood trial with the hope of finding justice for their teenage daughter, but were let down in the most crudest manner.

Weekend Review spoke to Sen about the book and the case. Excerpts:

What motivated you to write the book “Aarushi”?

A year into the trial, in 2013, Penguin India asked me my thoughts on going beyond just newspaper reportage and writing a book on Aarushi Talwar. The idea was exciting, because the story had already sucked me in. The methods of the CBI were on display daily and dismayed me at times. Bizarre testimonies by the agency’s witnesses left me shaking my head. It appeared that the Talwars had to be held guilty at any cost.

But as the trial went on, I began to understand that the story went well beyond just the murders or whether the Talwars were guilty. This was, for me the story of how India looked like from the ground. This was compelling: it was a story that needed to be told.

It was made richer by the context — a massive democracy on the path to prosperity, but held back perhaps by the repressiveness of a large section of its citizens and a number of its supposedly trusted institutions. The case articulated this truth every day.

The burden of public sentiment is heavy, and fell on two citizens — middle class parents — pitted against the state. For both the media and the state machinery it was easier to go with what society “felt”, rather than what the evidence said.

As journalists, we need to be aware that being censored by the government is not what we should feel most worried about. In some ways, our biggest challenge comes from public opinion and which way it is going — and our temptation to follow it.

Are you hopeful that your book will lead the judiciary to see the case in a new light, that is, without prejudice towards any party?

I hope, first and foremost, that the book reaches the widest possible audience. That it leads to serious conversation and reflection — including, but not only, within the judiciary. If that happens, justice will surely follow.

It is the first time that one has read that Aarushi’s bedroom was accessible from the bathroom of the guest room.

Yes, it was seldom recalled during the investigation and the trial. The door to Aarushi’s bedroom was not the only way to enter her room. The guest washroom allowed access to her toilet, and thereafter into her bedroom. To this day, very few people are aware of this fact. But does it not open up the possibility of an assailant entering Aarushi’s room through her toilet without having a key or being allowed in?

Strange are the ways of life — how maid Bharti Mandal’s testimony changed the lives of the Talwars.

Three different investigators questioned Bharti within a month of the crime. Yet she never mentioned to any of them that she had “touched” the iron door on the outside and it would not open. But her testimony suggested she tried unsuccessfully to open the front door on the morning when Aarushi was found dead.

This testimony was important for the CBI to establish that if Talwars were locked inside, no outsider broke into the house. And the “twisted” statement shifted the burden of proof entirely on to the Talwars: they had locked the flat from the inside, so it was up to them to explain how their daughter and servant were killed. No attempt to investigate was made.

It was quite chilling to read about your meeting with K.K. Gautam, the retired Uttar Pradesh police officer, responsible for the discovery of Hemraj’s body in the Talwars’ house.

He was quite specific that when a murder takes place, that’s where a pool of blood is found. And that there was blood all over the terrace, where Hemraj’s body was found. There were palm prints on the walls, which meant that there had been a scuffle and Hemraj struggled with his assailants there.

Gautam claimed that Hemraj was a very healthy man and four policemen had to pick up his body and they rested on each stair, implying it was impossible for the Talwar couple to have handled his body. The possibility or the opinion that Hemraj could have been killed on the terrace was not considered at all.

That the Talwars were fighting a losing battle is evident from the many facts provided by you in the book.

It’s astonishing how the Talwars would never be given any indication as to which prosecution witness would appear at the next hearing and then be expected to cross-examine them the day they appeared.

Frustrated by the daily surprises being sprung on them, the couple pleaded with the court several times to direct the prosecution to let them know which witness was being called on the next date. But while even the court would know which witness would appear, only the Talwars were kept in the dark. That is how the system worked.

It is shocking how the CBI had a free hand and judge Shyam Lal did not allow testimony of some witnesses the Talwars wanted.

The prosecution had used 39 witnesses, but when the Talwars filed their list of 13, the CBI responded by saying that not one of them was of any use to the trial. The court chopped the Talwars list down to seven. For the Talwars and their lawyers, it was like banging their head against a wall.

That the CBI and the lower judiciary have a free hand to do their jobs is in itself a welcome thing. But this doesn’t mean there can be no oversight. And, more importantly, no questions from the institution that watches all others — the media.

What is shocking about this case was that daily injustices were being overlooked. The Talwars had lost the battle of perception a long time ago. In the public mind, they were guilty. What was playing out at the trial seemed almost a formality — just the paperwork for a case that had been settled long ago. That is shocking. And unjust.

What had kept the Talwars going with both the CBI and the courts up against them?

A combination of things. Their need to redeem the reputation of their daughter that was dragged through more dirt than you will find in all the drains of India. The support they have received from family and friends through their interminable crisis.

Ironically, also the kind of sympathy they have received in prison, where the idea of injustice isn’t an abstraction — undertrials to name just one group, live without justice or closure for years.

Nupur told me that if she feels guilty about anything, it is not thinking about her daughter enough. And that’s because they haven’t been given the chance to grieve — what they have been forced to do is dig deep into their wells of courage, tap into every ounce of their instinct for self-preservation. They say they can’t break, for Aarushi’s sake.

It’s both scary and alarming how the most trusted investigation agency can manipulate and distort facts. And even then every other individual still seeks a CBI probe when the local police fails them.

I think the halo around the CBI is somewhat less luminous these days. Its record in recent times hasn’t been pretty. And it is increasingly viewed as a vehicle for political vendetta rather than the noble institution its founders imagined it to be.

What this case does is illustrate the perverse nature of its supposedly routine work; its disregard for ethical investigation and encouragement of the opposite. That this was happening in a case involving two ordinary citizens should make people think again, each time they ask for “a CBI probe”.

This book, through numerous examples, asks: “Really, is this the kind of team we are paying for?”

Did you get threats of any kind while working on the book?

Just a mild form of intimidation by some individuals on the CBI’s side when I was covering the trail. Nothing that I couldn’t handle.

Have Rajesh and Nupur read the book? What has been their reaction?

I believe they have. I think the fact that it is so graphic makes it hard for them — the book makes them relive several traumatic events. But they also see hope and see redemption of their child’s reputation in it.

The case and telltale signs

On May 16, 2008, Aarushi Talwar was found murdered in her apartment at Jalvayu Vihar in Noida, Uttar Pradesh. A day later, the body of Hemraj, the 45-year-old servant of the Talwars, was discovered from the terrace of their house. Sadly, there was no Hercule Poirot to solve the murder mysteries.

But within a week, the Uttar Pradesh Police declared they had cracked the case and accused Rajesh of the double murders. This created a furore and led the court to direct the CBI to investigate the case.

The CBI could not find any evidence and in December 2010 it sought the court’s permission to close the case. But not before making numerous insinuations against both Nupur and Rajesh. The Talwars were appalled. Seeking justice for their daughter, they challenged the report asking for a proper investigation with the hope of proving their innocence in court.

In hindsight, the Talwars would be wondering if they should have bothered at all for the judgment to be re-written. They underestimated the investigating agency and pinned false hopes on the judiciary, which dealt one crushing blow after another. On November 23, 2013, the court pronounced the couple guilty of the two murders.

Nupur and Rajesh were sent to Dasna prison in Uttar Pradesh and their appeal is pending in the Allahabad High Court.

During the trial in the Ghaziabad court, Sen, who covered the case for a Mumbai-based daily newspaper, had been meeting the Talwars, the CBI officers and lawyers, and gained access to documents related to the case. In the introduction of his book he writes: “I felt it was my duty to examine the course of the investigation, read the documents that were in the public domain, access those that were not, and talk to people connected with the case.”

Sen has quoted numerous people connected with the case, including the judge, the CBI officers and the forensic experts, whom he met after the verdict. There are no unnamed sources. He claims, “All significant interviews in the book are on tape. The rest are recorded in carefully taken notes, or e-mail exchanges between me and the interviewees.”

The revelations in the book, divided into three parts — the investigation, the trial and the Dasna diaries, leave one shocked. The book raises innumerable questions.

Sen provides description of how in 2012, the couple had pleaded to have the case shifted to a court in Delhi, since they had moved to Delhi and were afraid that the Ghaziabad court would not conduct a “fair trial”. However, the High Court and the Supreme Court not only turned down their request but also reprimanded them for trying to “delay the trial”.

Sen maintains that by June 2013, the “haste” on the part of Judge Shyam Lal was evident. He was to retire in November and was desperate to end the case during his term to add the “historic” case to his portfolio. The author’s meeting with the judge (after he had retired) reveals the most astonishing information — that the guilty verdict in the case was already being worked on even before the defence counsel had begun his final arguments on October 24, 2013. The judgment was pronounced on November 25.

Sen has provided disturbing details that reflect how investigation, if done wrongly and with evil intent, can destroy lives.

In the book, he has included the reports of the narco-analysis, brain mapping and other tests conducted by the Forensic Science Lab, Gandhinagar, Gujarat, on all the suspects — the Talwars and three domestic helps, Krishna, Rajkumar and Vijay Mandal.

He writes: “The story contained in the scientific reports of the servants has never been told. The documents were buried. Until now.”

Based on the reports, behavioural scientist Dr S.L. Vaya told the author that the Talwars consistently appeared innocent and the three helpers guilty. Vaya found herself engaged in a power struggle with M.S. Dahiya, a supposedly pliable scientist, who had developed a good rapport with CBI’s investigating officer A.G.L. Kaul.

Sen writes: “Vaya says, ‘When Dahiya was submitting his report, we had a meeting, where I said it did not make sense that two diametrically opposite reports are sent from the same institution. His attitude was, ‘you have sent your report, I’ll send mine,” and let us see whose is accepted.’” Predictably, Vaya’s report was buried.

The author mentions: “Two months after the Talwars had been convicted, Kaul travelled to the Gandhinagar lab with another case. At what used to be Dr Vaya’s department, he met one of her juniors, Dr Amita Shukla, who had been involved in the tests done on the Talwars and helper Rajkumar. She told Kaul, ‘Why have you come to us? What is the point of doing tests for you if you either dismiss them or twist reports?’ Kaul replied that it was his job as an investigator to use what he needed for prosecution. ‘But you had all these tests conducted, why didn’t you at least allow them on record? Let the court make up its mind after that.’ Dr Shukla remembers Kaul laughing and saying, ‘Madam, if we had placed all your tests on record, the case would have turned upside down.’”

Nilima Pathak is a journalist based in New Delhi.