My decades-long romance with the camera

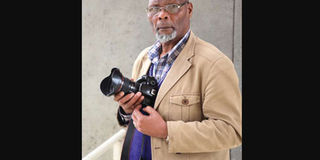

Photojournalist Paul Waweru in this picture taken at Nation Centre on August 5, 2015. PHOTO| BILLY MUTAI

What you need to know:

Waweru’s favourite haunt has for years been Nairobi’s courtrooms. And he never waits for a company car to take him there.

Instead, he walks there early and combs through court documents to establish where the juicy picture – and story – is likely to be.

The universal regret at ageing does not apply to Paul Waweru. His newsroom nickname is Babu, Swahili for grandfather, and the 68-year-old photojournalist, a veteran of four decades and still counting, just loves the sound of it.

“I really like that nickname,” he says as if it was a treasured birthday gift.

Waweru’s favourite haunt has for years been Nairobi’s courtrooms. And he never waits for a company car to take him there. Instead, he walks there early and combs through court documents to establish where the juicy picture – and story – is likely to be.

Later, much younger reporters are likely to be frantically calling him on his mobile phone asking: “Babu! Where are you? What is happening? In what court is this case?”

He’s normally happy to oblige – more so when the exclusive photo is already in the bag. And then he will walk all the way from the Milimani Courts to Nation Centre. That’s as far as his exercise regime goes.

He has been a newsroom fixture since 1978 – all spent in either Old Nation House along Tom Mboya Street or its successor, the Nation Centre on Kimathi Street. Journalists in Kenya have a reputation for “defections”, moving from one media house to another, but not for this native of Kijabe who started off in Eldoret before finding his way to Nairobi.

THE NATION IS HIS HOME

The Nation is home, the Editorial Department is family and he conservatively estimates he has some 20 years left on the clock.

Legendary journalist Joseph Karimi was the news editor at old Nation House when “a young” Waweru came along with his trademark goatee. He was 31.

“Waweru never ages and he never changes,” says Karimi. “The way he looks today is how he looked in 1978. He is a very agile old man — a challenge to the youth — very interested in what he does, very diligent, and thorough. He joined at a time when our photographic department had professionals like Joseph Thuo, Joseph Odiyo, Azhar Chaudhry, Njenga Munyori, Yahya Mohammed and Hos Maina.

“Payments for freelance photographers were a modest Sh10 per column and a photographer could rarely rate more than two columns at any one time. But Waweru slogged on, climbing inch by inch, year after year. He is a salute to endurance and focus,” says Karimi.

The veteran journalist adds that Karimi’s good character has also served him well since joining the newsroom in the 1970s.

“There were brilliant photographers who fell by the wayside because of their poor personal conduct. I used to get calls from wives asking me how long assignments to their husbands out of town were going to last when no such things were happening.

DISCIPLINED PHOTOGRAPHER

The fellows were just entertaining women somewhere in town while their families suffered. Sometimes I was forced to send money to their families and figure how to deduct it from them later. I never had such cases with Waweru,” he said.

He learnt to fend for himself early, acquiring an austere discipline in the process. Born to clergyman father and a peasant mother in the picturesque hillsides of Kijabe in the Rift Valley in 1947, Waweru saw his parents’ family of eight become destitute when his father was carted off to detention by British colonialists and died there.

He was a pioneer pastor of the African Inland Church who had refused to take the Mau Mau oath. In vengeance, Mau Mau sympathisers connived to lie to the authorities that he was one of them, a story that was believed, and thus his sad fate.

Life for the large family headed by an illiterate mother who was paid in onions and cabbages for her toils on the farm was sheer hardship.

His elder brother went off to Eldoret to try his luck as a stone mason and Waweru followed him. But daylong mkorogo (mixing sand, cement and ballast) was just not his kind of work. He was in love with the camera.

He found his way into Nairobi and his lifelong romance with photography, which he had flirted with on and off from primary school, took flight.

“When I started off,” he says, “I was using a roll of film which had eight or 12 exposures. The first cameras were, well, Stone Age. My first camera was called Click. With that one, you routinely chopped off your subjects’ head and limbs; you couldn’t focus,” he says.

Then came Lubitel II, which was slightly better. “Older people will recognise it as the one you strapped on your neck and held it against your stomach as you looked towards your feet to see the viewfinder. You counted ‘one, two, three!’ before snapping your subjects,” he says.

But at least with that model, a photographer could focus—even though it was bulky.

FIRST MODERN CAMERA

“My first modern camera was a Yashica. Still, it was a case of taking your black and white pictures to the dark room, processing them into a contact sheet and having the unused exposures in our film returned to you — a very elaborate process!” he says.

Waweru contrasts that with digital technology today — including on mobile phones — where one can immediately tell whether the picture is in or out of focus.

“Things are a much easier now. Older people have challenges adapting to new technology but my own experience has been the opposite,” he says.

Waweru initially did modest commercial photography in Nairobi’s Kangemi, establishing a makeshift studio next to a kiosk run by his wife. At the same time, he studied the newspapers and magazines and was convinced he could take pictures just as good as those he saw in them.

In his commute home from town to Kangemi, there was a sharp bend near Kianda College that accounted for road accidents almost daily. He positioned himself there and rushed the photos to Nation House where, without fail, they were used, complete with by-line.

Touts got to know him and reported to him wherever there was an accident. It seemed as if he had become an “accident photographer” of sorts with colleagues hailing him on sight as: “How many dead today?” Then that changed.

CHANGE OF SCENE

“One day, Wangethi Mwangi, who was the Daily Nation Chief sub-editor, called me and asked: “Paul, aren’t there other pictures you can take except road accidents?” Then he answered his own question with the instruction: “Go for other pictures from now onwards, but I am not saying you stop taking those of accidents,” he says.

His first change of scene was PCEA church, which always had functions. Then from there he started going to political meetings.

“One of the most memorable was Kuria Kanyingi handing over a heap of notes during a harambee meeting. Many readers gawked at the picture before such became commonplace,” he says.

As Karimi noted, Waweru would finally find his niche in the courtrooms. And here, he has tales to tell.

“All sorts of people come to courtrooms,” he says. “I have sometimes run into people who tell me: ‘Here, take this (money), and please don’t use my picture in the newspaper.’ When I refuse, they say to me: ‘You must, or else I will report you to the person who sent you here (the editor). I know him. I will tell him that you were demanding a bribe from me. I will make sure you are fired’,” says Waweru.

His trick is to report to his editor such encounters with the influential people in court corridors.

“Over the years, I have also seen such people get conned in their desperation by imposters with cameras who promise that the pictures won’t appear in the following day’s newspaper – and yet those quacks have no papers to report to,” he says.

TALES OF INTIMIDATIOM

Then there are the tales of intimidation. There was the 2005 murder trial of Bishop Luigi Locati of the Catholic Diocese of Isiolo. One of the accused, Father Guyo Waqo, looked threateningly at Waweru and warned him against taking his picture. But the photographer was adamant.

He told Father Guyo: “The fault is not mine. For that you should ask the police who brought you here. I am just doing my job. And look at these corridors; we are going to run into one another in them for a long time. We can’t help it. Given the circumstances we find ourselves in, my suggestion is that we become friends.”

Somehow, the accused mellowed. In fact, as the trial dragged on, they became friends of sorts. The priest and five others were sentenced to death last November.

“Some people tell me that I should be afraid of the people whose pictures I take looking very low in handcuffs or just shell-shocked in the dock. Some are very rich and powerful people who most probably, in their worst nightmares, never imagined they could find themselves there,” he says.

***

‘Hos Maina, the peerless one, made me what I am today’

ROY GACHUHI

Twenty-two years after his violent death in Somalia, Hos Maina, a former Nation Media Group and Reuters photojournalist, continues to inspire old colleagues and a new generation of news people in Kenya and beyond.

“I admired Hos Maina tremendously,” says Waweru. “To me he was the best. He was my inspiration. He gave me many tips about photography – he was such a generous man, no considerations of competition whatsoever. He was one man completely free of peer jealousy and was everybody’s friend.”

Hos and three colleagues were murdered by an enraged mob in Mogadishu, Somalia, on one of world journalism’s darkest days: Monday July 12, 1993.

ATTACKED BY ANGRY LOCALS

The four were separated from a convoy of media cars as they tried to photograph a United Nations helicopter assault and were attacked by angry locals.

Killed with Hos were fellow Kenyan photographer Dan Eldon and sound technician Anthony Macharia, all of Reuters, and German photographer Hansi Krauss of the Associated Press.

Hos established himself in Kenya during the uinsucessful 1982 coup. Waweru was with him in the streets of Nairobi as mobs ransacked the city after Air Force soldiers announced that they had overthrown President Daniel arap Moi’s government.

Hos traversed the city carrying his camera inside a kiondo (traditional Kenyan bag carried by women) covered with sukuma wiki (kales).

Each time he saw a good shot, he pulled the camera out, snapped, and returned the camera in the kiondo. When confronted by troops and looters, he said he was just looking for food for his family, as they could see for themselves. If he hadn’t been that resourceful, he most certainly would have lost his camera to the looters or been killed by the highly excitable soldiers.

They got marooned in old Nation House that night, there being no transport home, and drunk the last milk-less and sugarless tea to the dregs before being relieved the following morning.

Without cigarettes, those who smoked puffed at rolled up newspapers before they ran out of matches.

Almost all the pictures of the coup attempt in the Nation of August 3, 1982 — there wasn’t any edition the previous day as five hungry and scared journalists couldn’t produce one — were by Hos Maina.

Says Waweru: “Hos Maina was in a class of his own.”